The latest edition of REDI-Updates is out now - providing expert data insights and clear policy guidance. In this edition, the WMREDI team investigates what factors are contributing to the cost-of-living crisis and the impact it is having on households, businesses, public services and the third sector. We also look at how the crisis in the UK compares internationally. On the back of the Covid-19 pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis is the second recent health emergency to hit an already beleaguered population. Anne Green looks at what this means for the health and well-being of the UK. View REDI-Updates.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered a health emergency. It exposed structural and systemic inequalities in society that have health implications, and ultimately for life and death (Longevity Science Panel, 2021). The Health Foundation (2022) notes that the cost-of-living crisis (i.e. the fall in real disposable incomes that the UK has experienced since late 2021) is a second health emergency (see Local Government Association, 2023). Importantly, this second health emergency has come at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic meant many people were already vulnerable. There is increasing recognition that the public’s health is an asset to the wider economy and society; poor health has implications for economic growth and societal well-being (Royal Society for Public Health, 2022).

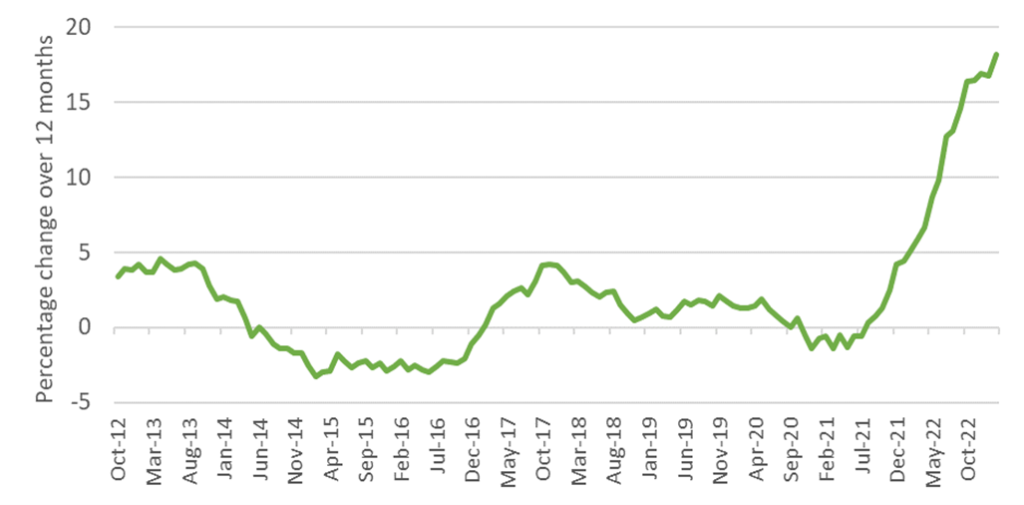

The scale of the pressures on individual and household budgets since 2021 is evident from ONS’s (2023) Cost of Living Insights. The price of consumer goods and services in the UK rose at the fastest rate in forty years in the year to 2022. The Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) was 9.2% in February 2023, slightly down from a peak of 9.6% in October 2022. Despite increases in average regular pay in 2022/23, inflation means three-month growth rates in average earnings have been negative in real terms since the final quarter of 2021, reaching a low of -3% in the quarter ending June 2022, followed by a gradual easing to -2.4% in the quarter to January 2023.

How the cost-of-living impacts on health

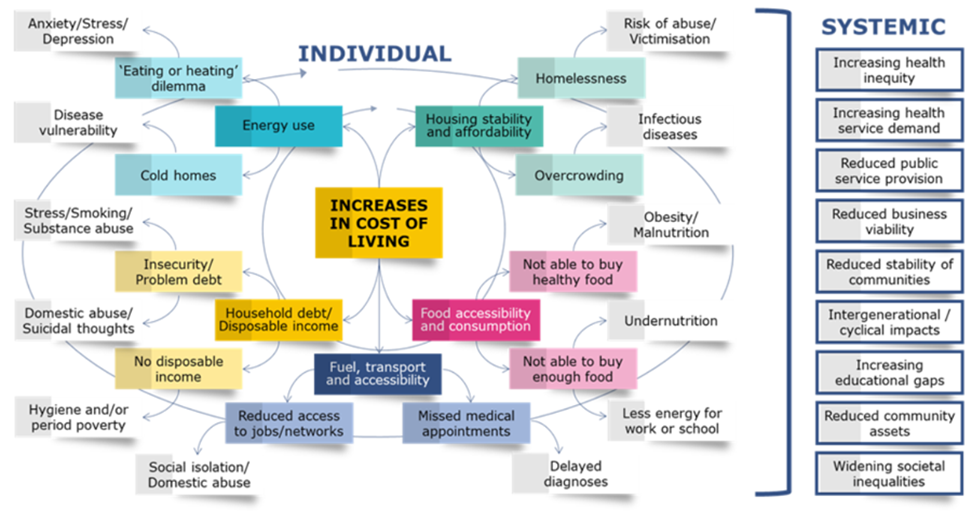

Figure 1 shows some of how the cost-of-living crisis links to health (Public Health Wales, 2022). It highlights the ‘material pathways’ between income and health (Broadbent et al., 2023). These include the increasing price of energy, housing insecurity, food access, transport costs, and accessibility.

Figure 1: Conceptualisation of how the cost-of-living crisis links to health

Concerns about housing affordability – amongst both owner-occupiers and in the private rented sector – can increase stress levels and in worst-case scenarios, housing insecurity may lead to overcrowding or homelessness, enhancing vulnerability and putting people at greater risk of poor health. Losing one’s home may also mean a loss of social support networks, leaving households to become ‘pressure cookers’, culminating in mental health problems (Longevity Science Panel, 2021).

Figure 2: Food and non-alcoholic beverages annual CPIH inflation rates, UK

Rising fuel prices and the cost of transport can mean reduced access to services, which in turn can have health implications. Most directly, missed medical appointments can mean delayed diagnosis and treatment of medical issues. Reduced access to jobs and networks also has implications for earnings and well-being.

During a cost-of-living crisis, more people find themselves on adverse ‘material pathways’, as those on low incomes who are struggling see their positions deteriorate further. Those on low incomes who formerly were just about managing can find themselves in crisis. The cumulative impact of exposure to the cost-of-living crisis on various fronts means that socio-economic inequalities widen.

Although sufficient money helps people to meet material needs for a healthy life, Broadbent et al. (2023) also identify ‘psychosocial pathways’ between the cost-of-living crisis and health. Poor mental health is a direct and immediate response to poverty. Anticipation of negative shocks and a sense of a lack of control regarding how one will cope in the future is harmful also, highlighting problems posed by insecurity of employment and/or income. In turn, despair can trigger risk-taking behaviours, which are linked to a rise in deaths related to drugs, alcohol and suicide. On all key personal well-being indicators in the UK – regarding life satisfaction, people feeling the things they do in life are worthwhile, happiness, anxiety and mental well-being – scores declined markedly with the Covid-19 pandemic and remain lower in 2023 than at any time over the last decade (ONS, 2023).

While it is easiest to focus on the short-term health implications of a cost-of-living crisis, exposure to stressors associated with such a crisis and other events can have implications over the life course. Delays in access to health services, and funding cuts in a cost-of-living crisis to social security, employment support and other services provided by the public and third sector can accentuate adverse health consequences (Broadbent et al., 2023).

Evidence from the Great Recession

So how is the current cost-of-living crisis different from what has gone before? Echoing Claudius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Wolf (2022), writing in the Financial Times in February 2022, highlighted how “economic sorrows come in battalions rather than singly”. Rising energy and food costs, high inflation and a weak economy have come on the back of the shock of Brexit and the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is a unique set of circumstances, with the Covid-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis operating in the same (negative) direction in terms of health outcomes. Nevertheless, it is instructive to look at the health impacts of previous economic crises.

The so-called ‘Great Recession’ from 2007 to 2009, like the current cost-of-living crisis, was felt internationally. A critical review of the international literature on the health impacts of the Great Recession on mental and physical health in developed nations found that the recession was associated with a decline in self-rated health (which likely represents a combination of mental and physical symptoms), and increasing morbidity, psychological distress and suicide (Margerison-Zilko et al., 2016). In the USA, in particular, already marginalised populations were hit hardest. Nearly all individual-level studies and most aggregate-level studies, across several countries, found that financial strain, job loss and housing insecurity were associated with declines in self-rated health. In the UK self-rated health declined over the long term. This decline was evident amongst those who remained employed throughout the recession, indicating that health impacts were felt beyond those most directly affected financially (Astell-Burt and Feng, 2013).

The evidence suggests that non-health policies may have played a role in mitigating the worst health impacts of the economic crisis of the Great Recession. Margerison-Zilko et al. (2016) found that stronger social safety nets in Europe than in the USA acted as a buffer in this respect for some populations. They identified active labour market programmes as reducing the negative effect of unemployment on suicide rates.

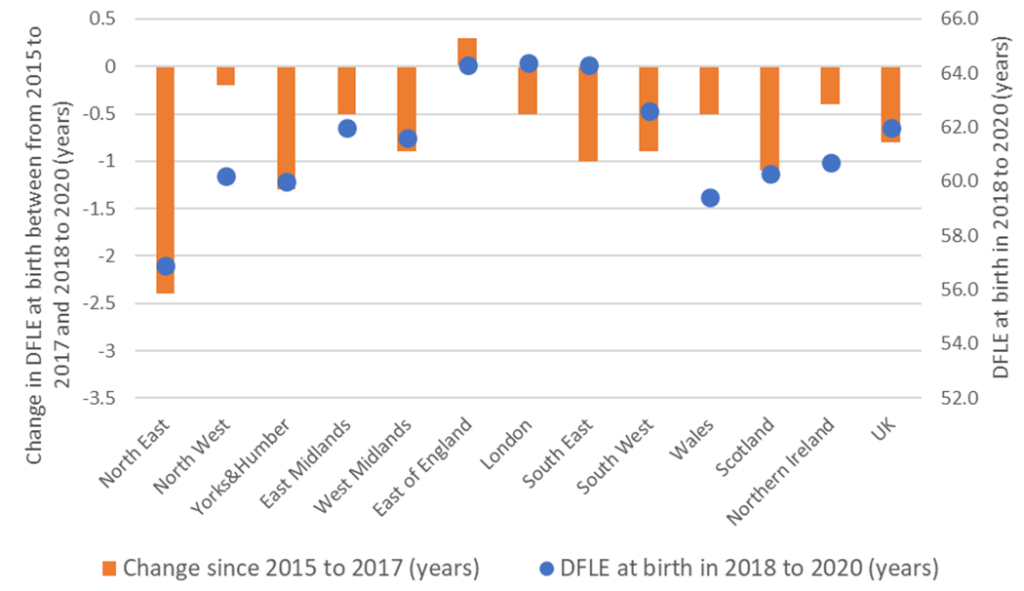

Focus on disability-free life expectancy

One key indicator of population health is disability-free life expectancy (DFLE). DFLE estimates the average number of years lived without restrictions on activity resulting from a long-lasting physical or mental health condition.

DFLE at birth decreased significantly for males and females in the UK between 2015 and 2017 and from 2018 to 2020 (ONS, 2022). This means that before the Covid-19 pandemic, DFLE was beginning to stall. Hence, following Covid-19, the population was already in a deteriorated state to deal with the cost-of-living crisis.

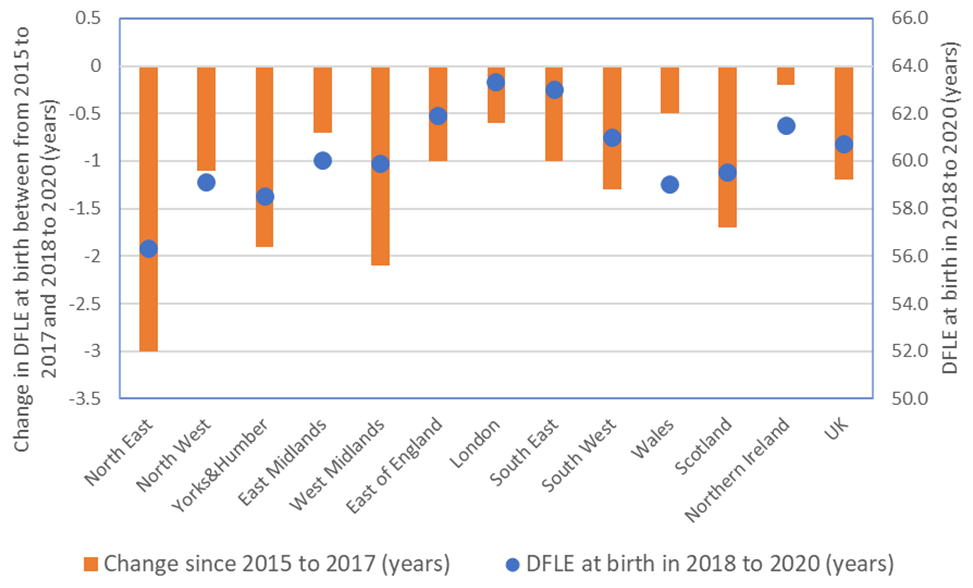

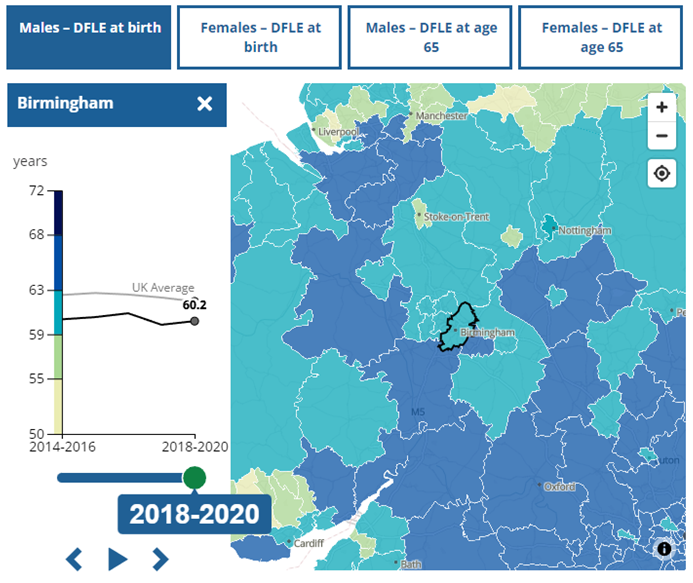

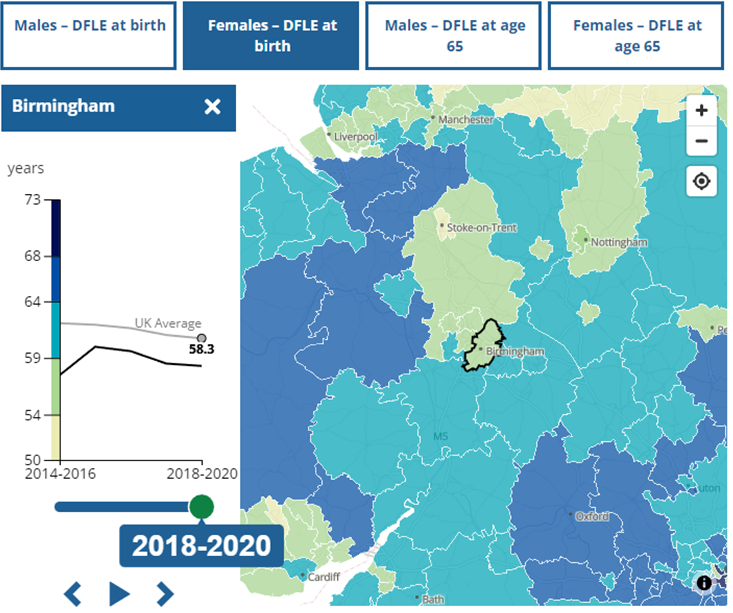

Figures 3 and 4 show the DFLE at birth from 2018 to 2020 (right-hand axis, shown by a blue dot) and the change in such DFLE over the period from 2017 to 2019 (left-hand axis, shown by orange bar), for males and females, respectively. In the case of males, DFLE changed significantly negatively from 2015 to 2017 based on non-overlapping confidence intervals in the North East, Yorkshire & the Humber, the South East, Scotland and the UK. In the case of females, DFLE changed significantly negatively from 2015 to 2017 based on non-overlapping confidence intervals in the North East, and the North West. Yorkshire & the Humber, the West Midlands, the South West, Scotland and the UK. Absolutely and relative to other English regions and the devolved nations, the change in DFLE is more severe in the case of females than males.

Figure 3: Disability-free life expectancy at birth estimates for males, 2018 to 2020, and change since 2015 to 2017, for males – English regions, countries and the UK

Figure 5: Disability-free life expectancy at birth estimates for males, 2018 to 2020

Figure 6: Disability-free life expectancy at birth estimates for females, 2018 to 2020

Policy Implications

Austerity has been identified as making an important and causal contribution to poor health (Margerison-Zilko et al., 2016; McCartney et al., 2022). Cuts to local services, pressures on health and social care provision, and any failure to raise benefits in line with inflation exacerbate the situation.

To alleviate the negative impact of the cost-of-living crisis on health it is necessary to mitigate short-term effects at the same time as tackling the underlying causes of poor health. Many different organisations and agencies, working across different policy domains at different geographical levels, have a role to play here. The Local Government Association (2023) acknowledges that it has a key role to play in promoting and linking initiatives tackling health and prosperity. It has a cost-of-living hub designed as a repository for sharing case studies, resources and data on good practices across different policy domains/areas. It also argues that public health has a role to play in developing a clearer narrative on the interconnections between education, training, work and health. Broadbent et al. (2023) argue that more refined integrated economic and health modelling has the potential to inform policy integration.

Possible policy responses at national and sub-national levels to address the stalling of DFLE and to address the negative implications of the cost-of-living crisis on health are presented in Figure 7. These highlight the need for policies across policy domains and for action at different geographical scales. A comprehensive multi-faceted approach to addressing health and well-being is necessary.

Figure 7: Possible policy responses to mitigate the negative impact of austerity and the cost-of-living crisis on health

| Policy domain | National policy | Sub-national/ local policy |

| Macroeconomic policy | · Design fiscal policy to avoid austerity approaches which limit public spending | · diversify economic ownership (e.g. through Community Wealth Building) to reverse or mitigate the processes of rent extraction |

| Social security | · Increase benefits and tax credits in line with inflation | · Provide high-quality money advice and welfare rights services – and enhance benefit take-up |

| Work | · Improve availability of ‘good work’

· Adopt real living wage |

· Use public spending to advance progressive work practices

· Maximise potential of growth/ devolution deals to reduce inequality and improve health |

| Public services | · Increase public sector funding for preventative services | · Co-design local services for the populations they serve |

| Material needs | · Eliminate fuel poverty through action on housing insulation and heating

· Increase affordable housing · Eliminate food poverty |

· Reduce the cost of public transport |

| Improved understanding | · Facilitate linkage between different government departments, NHS and mortality records to allow for the health and mortality impact of policy changes to be better evaluated | · Commit to ongoing monitoring and evaluation of relevant interventions |

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.