Welcome to REDI-Updates, a bi-annual publication which will get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. West Midlands REDI staff and guest contributors will discuss various topics, with this first publication focusing on how inclusive growth can be a tool to tackle regional imbalances across the UK. In this article, Dr Deniz Sevinc explores the effect of inequality on the economy and shows that if we really want to tackle this issue, we need to broaden the debate beyond just income.

Welcome to REDI-Updates, a bi-annual publication which will get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. West Midlands REDI staff and guest contributors will discuss various topics, with this first publication focusing on how inclusive growth can be a tool to tackle regional imbalances across the UK. In this article, Dr Deniz Sevinc explores the effect of inequality on the economy and shows that if we really want to tackle this issue, we need to broaden the debate beyond just income.

You can view and download the magazine here.

The issue of inequality is one of the major continuing problems in economics and it is set to stay at the top of the global debate. High and rising income inequality damage our societies, reducing social cohesion and political coherence as well as affecting the prospects for future economic growth. However, the current emphasis on income alone results in partial insights into who experiences inequality around the world and in what ways. Today’s global inequality of opportunity within countries is significantly large. Some countries have seen dramatic improvements, while others have not. There is a real danger of a self-reinforcing cycle establishing itself around the world, comprised of growing inequality of opportunity (education and skills, access to employment, healthcare and affordable housing) leading to a weakening of economic growth and greater inequality. The neglect of human life aspects, with an over-emphasis on income, is certainly part of the problem.

Inequality in the UK – Regional disparities in Income and Wealth

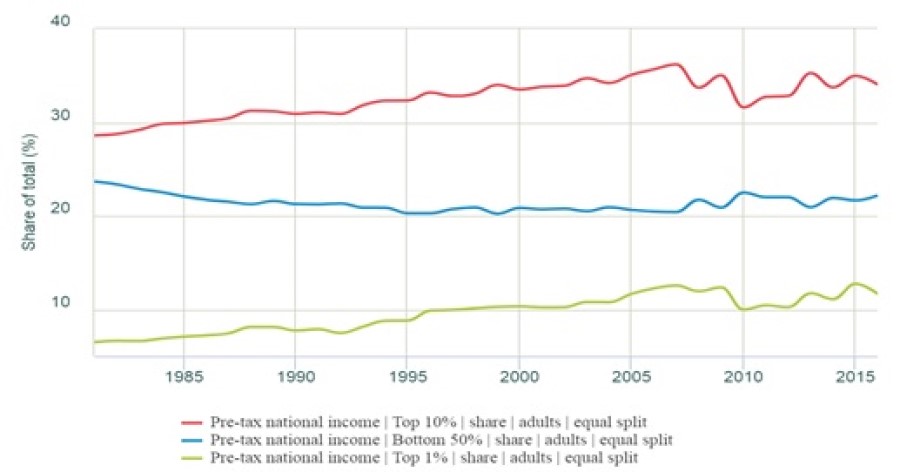

As far as income inequality is concerned, the UK is one of the most regionally unbalanced countries in the developed world and most recent figures suggest that the richest 1% of the population account for 11% of the total income, the top 10% control 34%, whereas the bottom 50% (middle class) have only 22% of the total income. Wealth in Great Britain is even more unequally divided than income. The richest 1% of society holds 19% of all wealth and the top 10% control 53% of total wealth. The bottom 50%, by contrast, own just 9%.

The issue of regional wealth inequality has been fertile ground for policy debate recently. Regional inequality is the outcome of a series of interactions between many different processes. Factors like technological change, globalisation, physical geography, firms, labour force diversity, economic opportunities form direct and indirect effects on regional disparities. It is vital to analyse these dynamics driving up inequality as a whole since they have both internal and external regional components.

In 2019, the ONS calculated that the South East had the highest median wealth in April 2016 to March 2018, at £445,900. This is followed by the South West (£372,600), London (£356,400) and the East of England (£348,800). The figure below provides a stark picture of wealth inequality by region.

The region with the lowest median total wealth was the North East at £172,900. The three regions with the highest median total wealth (the South East, South West and London) have all seen increases in median total wealth over time. The three regions with the lowest median total wealth in April 2016 to March 2018 were the North East, Yorkshire and the Humber, and the East Midlands. The East Midlands has the third-lowest median wealth and the region was closely followed by the West Midlands (ONS, 2019).

The West Midlands

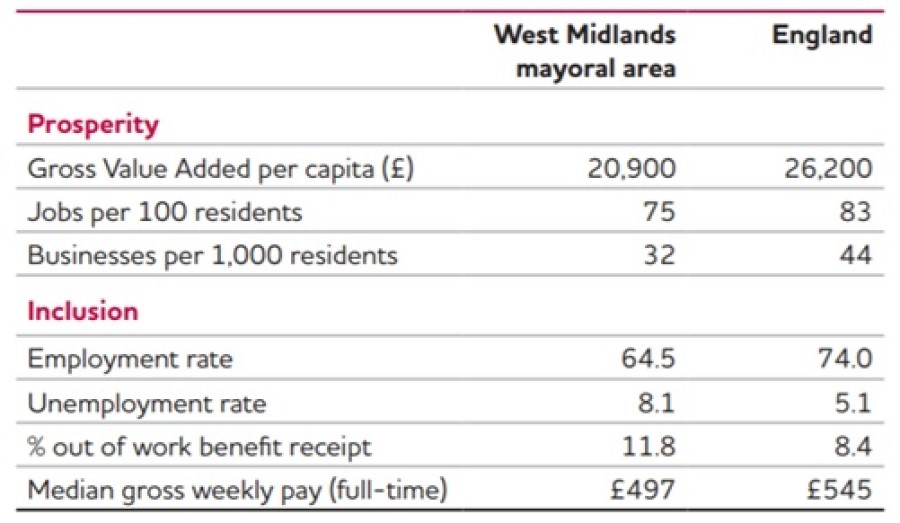

Although the West Midlands region attracts high levels of inward investment and remains top of the national league for exports, job creation and foreign business investment, inequality is still an ongoing problem facing the region. A valid concern here is that an increasing proportion of households in the region seem to find it difficult to make both ends meet. In the West Midlands, after housing costs are taken into account, overall 1.3 million people live in poverty and this is made up of 400,000 children (three in ten children). As far as labour market conditions are concerned, 12% of the working-age population in the region receive out-of-work benefits in comparison with 8% in England, and the employment rate (65%) is below the national average (74%). One in five working families depends on in-work tax credits in an attempt to increase their low pay that is significantly higher than the national average (one in seven). Added to this problem is the unequal distribution of qualifications at the regional level. It is worth noting that regional economic growth relies on matching local demand to the local supply of skills; attracting inward investment also depends on the availability of certain skills in a region. However, our recent studies uncovered a significant NVQ4 gap of some 120,000 candidates absent from the labour market in the West Midlands region indicating that even though the jobs are potentially there, new recruits with appropriate qualifications are not.

Reducing inequality

To prioritise interventions and develop a more effective strategy for reducing regional inequality, it is necessary to take into consideration the multifaceted channels operating in the UK to analyse how inequality has been shared among cities, regions, and generations over time, and how macro policies have affected growing disparities between different socio-economic groups. The future prosperity of the region depends on the development of such an integrated policy agenda that is committed to careful attention and generous investments towards closing the education attainment gap, supporting people to progress in work, connecting economic development and poverty reduction. It is only such a strategy that will transform local lives and produce better outcomes for the whole city region.

Thus, determining who the most deprived social groups are and in what ways they are experiencing deprivation is crucial for generating more effective, holistic inequality reduction initiatives. The complexities of multidimensional, longitudinal and spatial interdependencies between regions and within the West Midlands region needs to be understood in combination with a more robust knowledge about the redistributive effects of different government policies. We explore these important challenges in our studies at City-REDI and West Midlands-REDI in an attempt to shift the focus of societal development from an income-oriented approach to a people-centric one.

References:

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2017). Inclusive growth in the West Midlands: an agenda for the new Mayor.

Office for National Statistics. (2019). Total wealth in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018.

World Inequality Database. (2019). Global Inequality Database.

This blog was written by Dr Deniz Sevinc, Research Fellow for City-REDI / West Midlands REDI

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.