Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates aims to get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WMREDI staff look at the government's flagship policy - Levelling Up. We look at the challenge of implementing, understanding and measuring Levelling Up. Rebecca Riley and Ben Brittain discuss the need for a radical change in the way funding is distributed in the UK as well as a reform of local institutions. View REDI-Updates.

The age of ‘morbid symptoms’

Michael Gove gave the Ditchley Annual Lecture in July 2020, before he was reshuffled from the Cabinet Office to the newly titled ‘Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities.

In the lecture, he identified the current malaise of UK growth, distrust in democracy, and lack of faith in capitalism as an age of ‘morbid symptoms’.

Growth, he argues, has been slowing in the UK, and its benefits have been concentrated in the hands of the ‘already fortunate’. High-skilled workers have often seen a return on their labour, but those workers in low-skilled manufacturing roles have seen little return with many jobs offshored and wages undercut in an age of globalisation and mass migration.

The medicine for this age of morbid symptoms is, Gove argues, to reform capitalism, reinvigorate support for democracy and ‘get Government working better for all while building more inclusive societies.’

Levelling up White Paper

The Levelling up White Paper reflects this view; the paper presents a step-change in the approach to economic geography and structures. The first 2 chapters draw out both strong evidence but also a different approach to the country and its place assets.

However, to achieve this the machinery of government must change. Real change requires real reform, and it requires structural reform of government. The government’s levelling-up agenda is a prescription to help cure the UK’s current low-growth, low-productivity malaise, but the ingredients must be right. There has been a considerable response to the paper, and much of it is centred on whether the vision in the paper will flow through to organisational and operational delivery.

The reform of local institutions

Firstly, the reform of local institutions will face the challenge of ensuring they are invested in delivering programmes that are more tailored to local needs. To achieve that appropriate and real devolution is going to be crucial.

We can draw on our research at City-REDI to reveal the embedded structural problems within the current structure of sub-national governance.

In her research, Professor Anne Green looked at the spatial economic architecture of the Midlands, conducting an audit of local and sub-regional economic development strategies and plans. The audit revealed that some regional ‘strategies’ are in fact just ‘visions.’ Not all have numerical and tangible targets that would be needed for evaluation, not all identify the funding required for intervention and often targets relate to closing a gap, which suggests even a minimal closure of identified gaps could be seen as a ‘win’.

Mismatch of funding and the needs of a local place

This is also a feature of the mismatch between funding that is devolved and the needs of a local place. Lack of devolved funding and capacity can lead to a place knowing exactly what they need to do to level up, but a misalignment with the financing they win, or which government devolves.

As Gove identified in his lecture, the government needs to be rigorous and fearless in its evaluation of policy and projects, alongside the need to evaluate data more rigorously. This should not be reserved for central government capital projects but also for local authority and combined authority projects. However, the capacity and capability at this level have been hollowed out and need rebuilding. The government itself also has to heed Treasury’s guidance on place-based assessments and ensure projects and programmes are assessed across the board for place impacts and ultimately the impact on levelling up.

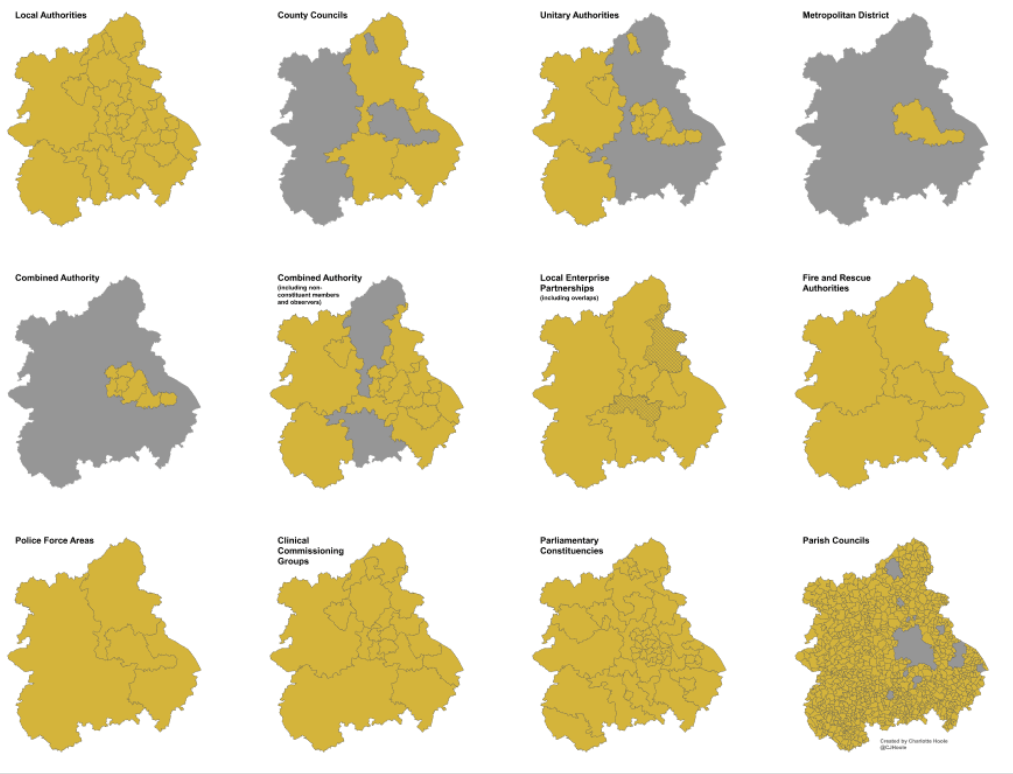

The Complexity of Local Government

Alongside this, local governance is often geographically uneven and unnecessarily complex, with a mix of statutory and non-statutory organisations and responsibilities that have developed in an ad hoc manner, usually in response to government policy. This poses difficulties for gaining a clear line of sight between sub-national and national policies. Additionally, the government’s use of ad hoc funding pots, which local authorities must bid for, compounds coordination problems. There is also variation by the department on how they handle delivery at a local level, which adds to the confusion. The White Paper goes some way to suggest changes to this structure, but the language used is still couched in advisory terms.

Reviewing competitive funding model

The competitive funding model allows larger and better-resourced governance structures to prepare and submit bids to the central government, often meaning rural and smaller urban local authorities are at a disadvantage, unable to prepare bids without being resource intensive or outsourcing to expensive consultants, with no guarantee of success.

Reviewing one recent fund that exemplifies the competitive approach, on 3 November 2021 the UK government announced a list of 477 successful bids (from 1,073 submitted) for its Community Renewal Fund (CRF). The fund supports investment in skills, local businesses, communities and places. The winners across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will share a total of £203m, all to be spent by the end of June 2022.

In public expenditure terms, the CRF is modest, but it is supposed to prepare the way for the new UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UK SPF), intended to replace EU funding and be worth on average £1.5bn a year. Underpinning the CRF and SPF should be local needs and it should be guided by the overarching agenda to ‘level up’.

The WMCA submitted 23 bids and was awarded 8; of those 8 many were not the highest score of the 23. The successful bids were heavily focused on skills/employment, but no universities won bids and there was nothing on business support. This is a worrying signal if it is replacing EU funding which is a major funder of business support and university assets nationally. EU funding is also a source of match funding to leverage other public and private sector funding and its loss would lead to an overall reduction in wider funding as a result.

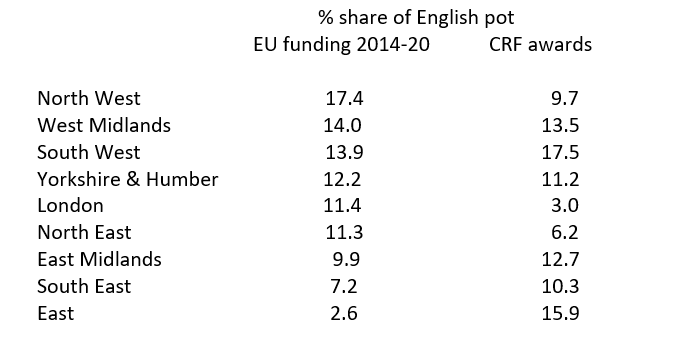

The successful CRF bids allocate money to projects submitted by county councils, combined authorities, Local Enterprise Partnerships and (elsewhere) unitary authorities. Adding up the awards to the regional level, and comparing the figures with the regional distribution of EU funding, show that the Southeast, East and South West see a substantial increase in their share:

The share of CRF awards going to the three northern regions – North East, North West and Yorkshire & the Humber – is just 27 per cent, down from 41 per cent of EU funding.

If this distribution of CRF funding were to be repeated in the allocation of UK SPF funding it would represent a major shift in resources to southern England and away from many of the places most in need of levelling up.

In addition to this, there were a total of 1,073 bids submitted to the Government for consideration. This figure also does not account for those that were sifted through and rejected. The competitive bidding process is resource and labour-intensive, requiring substantial effort from local authority (LA) officers and wider policy and business development managers to collate, write and align bids with Government’s criteria. Often LAs do not have the internal capacity to commit staff time, and many LAs do not have the expertise and skills within the organisation so the responsibility is contracted out.

The Business cast cost

The business case cost, which would account for the writing, approvals and reviewing costs of staff for salary and on costs at the local, regional and national level, could equate to a conservative estimate of just under £30,000 (without any use of consultants), This would mean the average bid can be estimated to cost £30,000. Across the West Midlands, there were 110 bids, totalling £3.3million. The average successful bid is however only worth around £500k. The West Midlands CA won 8 bids.

The £3.3million is a wasted resource which could be utilised to address and deliver prioritised projects, whether that be skills-focused, regeneration, housing or climate change initiatives.

Of the 1,073 bids submitted to the government, 596 were unsuccessful. If we use the baseline average of £30,000 per bid it equates to nearly £33m in wasted human capital that could be used elsewhere. The total amount of the CRF fund is £203m but deducting £33m on bid preparation is unnecessary waste. This cost is also hidden, it is in the operating costs of local organisations that do not have the flexibility to account for this cost; this means that even simply applying for funding the precious resources are taken away from other vital services and activities.

Funding uncertainty and a reliance on consultants

It shows that the competitive bidding process is a potent example of a wasteful government. This also came out in research conducted in partnership with WMREDI / City-REDI and the now disbanded Industrial Strategy Council (ISC) on subnational government. We found that funding uncertainty creates over-reliance on consultants, who are often more costly and have a limited positive impact on building institutional knowledge. Down the line, this can also lead to failures in operational delivery as these aspects are not built into the business case as effectively as they could be.

Internal capacity, particularly in analytical functions, was considered insufficient and held institutions back in terms of developing coherent evidence-based, long-term strategies and securing funds from central pots. Insufficient skills and capacity also limit their ability to conduct evaluations and learning.

The need for great fiscal devolution

To rectify this the ISC and WMREDI recommended greater fiscal devolution, particularly in terms of more devolved spending powers. This would enable funding to be spent on targeted, long-term interventions that address place-specific issues, issues can still be aligned with the centre but at a single pot programme level rather than piecemeal.

Multi-year, single-pot funding settlements are needed to create more certainty and enable longer-term strategic planning and implementation. More long-term investment from the public sector is needed to unlock local economic growth and ensure private investment follows. The benefits would be:

- Cutting down on waste at a local level where effort can be put into developing strong business cases, solid project delivery and evaluation capacity, improving outputs and keeping activity close to need;

- Increasing partnership working at a regional level where efforts are put into strategic investment decision making and alignment of projects and programmes, as well as specialised research, intelligence and technical capacity for the benefit of local partners;

- Reducing the reviewing and assessment burden nationally so that effort can be put into strategic portfolio management and evaluation;

- Across the board, it would be a more transparent process, with funding and accountability hand in hand

To cure the morbid symptoms of sub-national governance in the UK and achieve the ambitions Michael Gove outlined in the Ditchley Annual Lecture, we need to devolve down to level up.

This blog was written by Associate Professor Rebecca Riley City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham and Ben Brittain, Policy Advisor to West Midlands Mayor Andy Street.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI or the University of Birmingham

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.