The 20th of February has been designated by the United Nations as World Day of Social Justice. This year’s theme is “If you want peace and development, work for social justice”, with a specific focus on the 2 billion people worldwide living in fragile states afflicted by conflicts and how the creation of better quality jobs for these people can lift them out of poverty.

The 20th of February has been designated by the United Nations as World Day of Social Justice. This year’s theme is “If you want peace and development, work for social justice”, with a specific focus on the 2 billion people worldwide living in fragile states afflicted by conflicts and how the creation of better quality jobs for these people can lift them out of poverty.

These are noble aims and on face value it is difficult to disagree with the sentiment that the poorest people on the planet should have improved standards of living. The UN is encouraging a solution for global poverty through businesses creating more jobs with better pay and conditions. This raises some questions, such as: what is social justice? What do we mean by poverty and what are the causes of global poverty? And can we make a distinction between large multinational businesses and local entrepreneurs in terms of their impact on inclusive growth that lifts people out of poverty?

What is social justice?

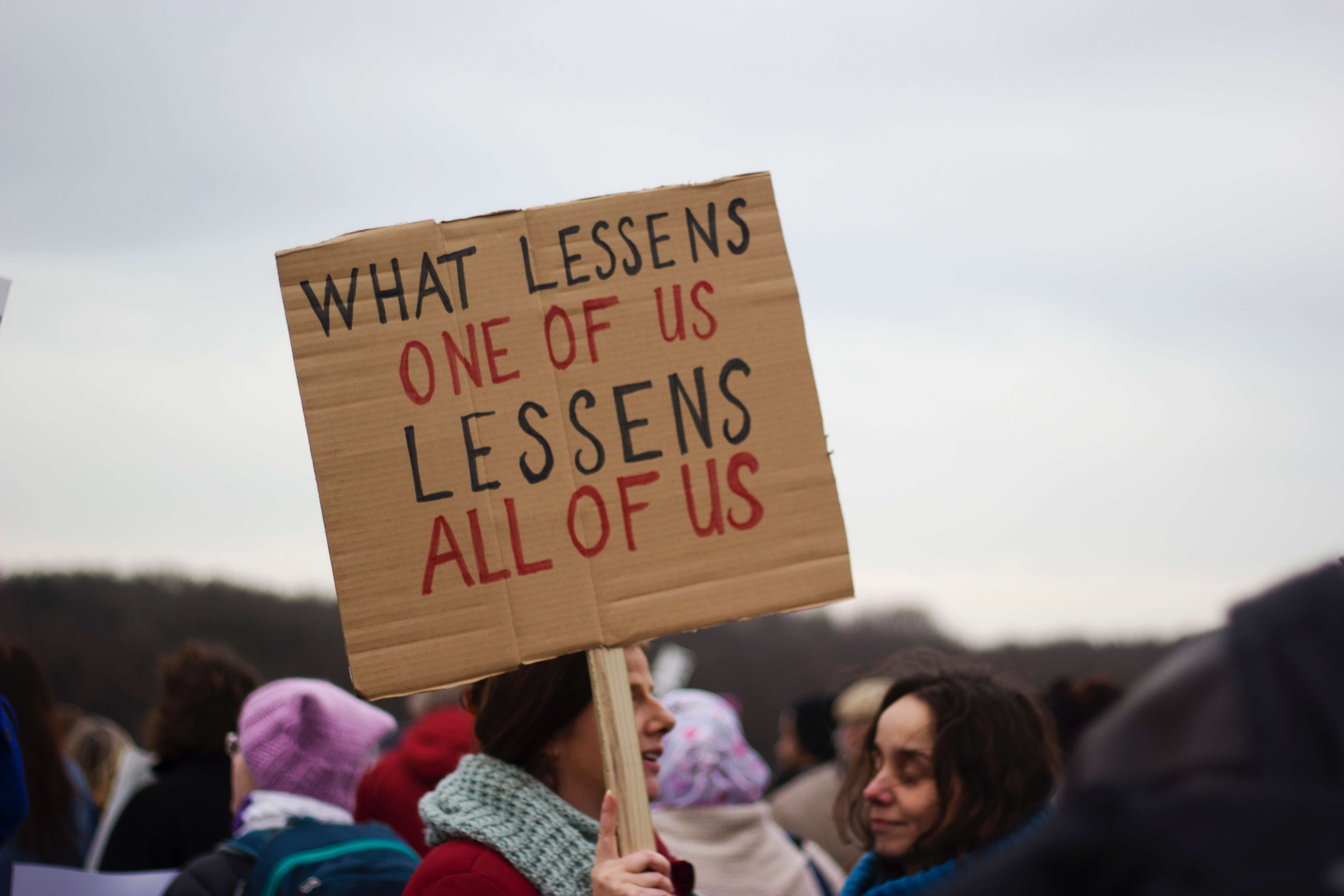

The theme of this year’s day of social justice is job creation, which the UN claims can increase incomes, contribute to more cohesive societies and prevent violent conflicts, along with addressing post-conflict challenges. This does not really address most of the facets of social justice, which is concerned with dismantling the systems and barriers that cause discrimination on the grounds of gender, age, race, ethnicity, religion, culture or disability.

There is always a tension when talking about something as universalist as “social justice”. For example, am I imposing my Western cultural values onto a society that does not want them if I advocate for LGBT rights or the equality of women in the workplace in a conservative Muslim state that has adopted sharia law? These are important debates to have with others as well as with yourself. I personally feel that the full equality of all citizens of this planet is something to aspire to, and we should not allow the ingrained prejudices of others to prevent this from being achieved. I also subscribe to the idea of “false consciousness“, which has its origins in Marxist social theory. In a nutshell, someone who is raised in a society that has taught them from birth that being gay is wrong, or that women are second-class citizens, will believe that they are making the free choice to oppress their sexuality or confine themselves to the home. In reality, their psychological framework has been so conditioned by the education system, media, and values of family, friends and wider society that it is very difficult for them to choose otherwise.

What does it mean to be poor?

We hear a lot of talk about the “top 1%” or “global elite” hoarding most of the financial resources and exerting too much influence over politics. However, on a global level most people in a country like the UK can be considered the elite. There is a tool developed by the site Giving What We Can that will estimate in which percentile of global income your salary puts you – and the result may surprise you. A person on the average salary in the UK belongs to the top 2.5% of the global population in terms of income. This global dimension is certainly something to think about when discussing poverty and inequality. After all, global GDP per capita is only around $11,000 per annum (approximately £8,300 in February 2019 prices). Earning more than this by default puts you in the “above average” income category.

The World Bank definition of “absolute poverty” is having less than $1.90 a day at your disposal (around £1.50), with 2 in 5 people in Sub-Saharan Africa living in this condition. However, we know that the minimum financial resources needed to achieve a basic standard of living – such as food and water, shelter, clothing and healthcare – vary according to local contexts. The $1.90 figure cannot accommodate the massive difference in the cost of fulfilling basic needs in states as different as Sweden and Somalia. For this reason, it is more appropriate to consider relative poverty, which is defined as the inability to reach a minimum acceptable standard of living in a society.

Relative poverty brings with it discussions about wealth inequality. We already know that in more unequal societies, social mobility is worse, health outcomes are poorer, and in the long-term economic growth is weaker [i]. There is a lot of debate in academia, policymaking and the media about the rise in inequality and its political and social impacts. Inequality is rapidly growing in developed economies such as the UK, USA and Australia, which a number of commentators have connected with the growth of political protest movements [ii].

Can big business bring inclusive growth to the developing world?

In my view, not enough attention is paid to one of the single greatest causes of poverty in the developing world: namely, the neocolonial extraction of wealth by multinational corporations (MNCs). While formal colonial empires have essentially vanished, their shadows live on in the economic exploitation of poor countries, especially in Africa. Around $1 trillion per year is extracted from Africa and moved by MNCs into tax havens – states such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or British Virgin Islands [iii]. Much of this capital flight is illicit; recent research estimates that up to 87% of capital flows out of Africa are the result of deliberate trade misinvoicing, whereby MNC subsidiaries in developing countries falsify the value of goods or services to move large sums of money offshore, frequently aided through the use of bribes and official corruption [iv].

The situation in Africa has been characterised as “aid in reverse”: for every $1 wealthy countries give in aid payments – often, it must be said, with conditions attached – around $24 is extracted by MNCs [v]. Poor nations frequently lack the diplomatic infrastructure, alliances and legal or financial capacity to challenge this state of affairs. They are more vulnerable to external pressure, such as through investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms, which use the threat of legal action to lock in place the terms of usually very unequal bilateral trade deals [vi]. It will be interesting to see what sort of trade policies the UK pursues after Brexit – will this be driven by ethical values or by protecting the interests of MNCs? We can probably guess the answer.

We cannot even say that the business activity by MNCs is enriching the local population through some form of “trickle-down effect”. Take the example of Angolan oil. Angola has one of the largest proven oil reserves on the African continent. 1 in 3 people in Angola live in extreme poverty, but at the same time there is an ultra-wealthy elite living in glittering glass towers in the capital of Luanda. The revenue from this moves through a series of shell companies beyond the country’s borders. Its final destination is frequently obscured through the right to privacy many tax havens use to protect the beneficiaries of offshore accounts. In this case, there is evidence in the documents from the Panama Papers leak that oil revenue frequently lands in the accounts of high-profile Angolan politicians and their supporters, with the big Western accountancy companies also taking a slice in fees for carrying out this complicated financial engineering [vii]. Similar cases can be seen elsewhere, such as in neighbouring Equatorial Guinea.

If not big business, then what about local entrepreneurs?

We see then that the big global corporations will not create the conditions for social justice as set out by the UN. Rather than investing to create more jobs, with better pay and conditions, these companies are extracting resources at a truly astonishing rate. It is also unlikely that these countries will be able to change the structure of the system of which their exploitation is a design feature – they are too poor, weak and peripheral to realistically take on the core of the global economy. Is it better to hope therefore that local entrepreneurs will be able to generate the jobs and wealth that poor countries need in order to become more developed economies?

There are a series of technological, economic, demographic, cultural and institutional factors that influence the business start-up rate in a country. Some research has suggested that in countries with higher incomes, low income disparities, large public sectors and a relatively low reported rate of dissatisfaction with life there are lower business start-up rates [viii]. However, it does not follow that poor countries have higher business start-up rates. In fact, for the most part the literature on entrepreneurship does not concern itself with poverty, instead preferring to look at high-growth and high-value businesses in developed states. Analysis in 2013 found that only several dozen among the thousands of articles on entrepreneurship considered poverty, most of which looked at North America and Europe [ix].

One scholar who has engaged with the issue of how entrepreneurship works in poverty conditions is Jeffery McMullen, who promotes the idea of Development Entrepreneurship [x]. This has been taken forward by the UK Department for International Development as the basis for future aid payments, based on the delivery of impactful, sustainable and scalable objectives following established program management practices and measurable criteria for selecting corporate and local partners [xi]. At the core is the adoption of iterative ‘learning by doing’ approaches taken from business, particularly tech start-ups. However, many developing countries are not ideal locations for business start-ups, above all due to severe instability. There are major wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Yemen; violent conflicts from West Africa across to the Horn of Africa; and dictators who clamp down on civil disobedience or population elements disloyal to the regime from Venezuela to Central Asia. There is also the question of how far the application of New Public Management techniques to aid payments will be effective.

The scarcity of resources and vulnerability to climate change of some regions, coupled with violence and religious fundamentalism, has seen tens of millions of people displaced across the developing world. Hundreds of thousands of these people move as refugees to developed countries each year and arrive traumatised by the sexual and physical abuse they endured on their journey. These people carry with them the potential to start new businesses, but more than that, they carry the potential to add to human civilisation. That might mean researching ground-breaking new cures for disease, creating new masterpieces of art, or even working in their new countries to foster dialogue and understanding between different races and religions. On this World Day of Social Justice, perhaps the UN has got it the wrong way round: without peace and development, there can be no social justice. A great start would be to make multinational corporations accountable to the societies they operate in to make sure that there are tax revenues to pay for the education, healthcare and infrastructure people need in order to survive and flourish. Perhaps even more importantly: if shelter, food and healthcare are basic human needs, why should anyone have to pay for them at all? How can we rearrange our political and economic system so that no-one should starve to death, or see their child die from an easily curable disease, while at the same time some people in some parts of the world live in luxury?

This blog was written by Liam O’Farrell, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The opinions presented here belong to the author rather than the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

[i] Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, K. (2010) The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London: Pengiun.

[ii] Sawer, M. and Laycock, D. (2009) ‘Down with elites and up with inequality: market populism in Australia and Canada’, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 47(2), pp.133-150.

[iii] Shaxson, N. (2018( ‘How to crack down on tax havens: start with the banks’, Foreign Affairs, 97(2), pp.94-107.

[iv] Salomon, M. and Spanjers, J. (2017) Illicit financial flows to and from developing countries: 2005-2014. Washington, D.C.: Global Financial Integrity.

[v] Hickel, J. (2017) ‘Aid in reverse: how poor countries develop rich countries’.

[vi] Turner, G. (2018) ‘Offshore firms use secretive court hearing in bid to stop Vietnam taxing their profits’.

[vii] Brönniman, C. and Zick, T. (2017) ‘Power to the (rich) people’, Süddeutsche Zeitung

[viii] Wennekers, S., Uhlaner, L. M. and Thurik, R. (2002) ‘Entrepreneurship and its conditions: a macro perspective’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 1(1), pp.25-65.

[ix] Bruton, G. D., Ketchen Jr., D. J. and Ireland, R. D. (2013) ‘Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty’, Journal of Business Venturing, 28, pp.683-689.

[x] McMullen, J. S. (2010) ‘Delineating the domain of development entrepreneurship: a market-based approach to facilitating inclusive economic growth’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25 (Special Issue: Future of Entrepreneurship), pp.185-193.

[xi] Faustino, J. and Booth, D. (2014) Development entrepreneurship: how donors and leaders can foster institutional change. San Francisco, CA: The Asia Foundation and London: Overseas Development Institute.