Previous blogs in this devolution series have considered the political and economic benefits of devolving decision-making power, looked at the situation in England, with the new combined authorities and the office of the Mayor of London and the form devolution takes across in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The next blog in the series looks at the state of devolution around the world.

In 2015, the then second permanent secretary at HM Treasury, Sharon White described the UK as ‘almost [the] most centralised developed country’. A discussion on the nature of devolution in the UK was in full force in the wake of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum.

There is a logic behind Sharon White’s statement of a heavily centralised country. Even with the major reforms of devolution legislation that was birthed in the Blair government, Westminster and ultimately Parliament are sovereign, not regional governments. In theory, devolution in a country with an uncodified constitution has very little protection- there is always the flexibility in the UK constitution to completely reverse all advances of devolution, and it would likely only take a major crisis or external threat for the region states to surrender their autonomy in return for protection. This outcome, however, remains very unlikely to occur, but observing the hypothetical certainly stands the UK out from other nation-states.

Devolution is a British colloquialism and has a negative connotation attached to it. It is an interesting choice of word for the UK government to use in that it can mean the opposite of evolution, as to lessen or diminish. In the international domain, however, other countries would simply refer to it as ‘decentralisation’.

Decentralisation

So what does decentralisation look like in other countries compared to the UK’s own version? Most countries can be loosely split into two systems of government, federations and unitary states. Although each country widely differs in its political architecture, there are far fewer federations (approximately over 20) than unitary states in the world, and plenty of these federations are countries with a far greater land area than most other States. Countries such as Brazil, USA, Canada, Russia, Australia and India are all larger in land area, however China bucks this trend as being a unitary state. It would make sense if federations are more devolved, or decentralised since there is a greater need for a regional government in a country with a vast amount of land and a different time zone.

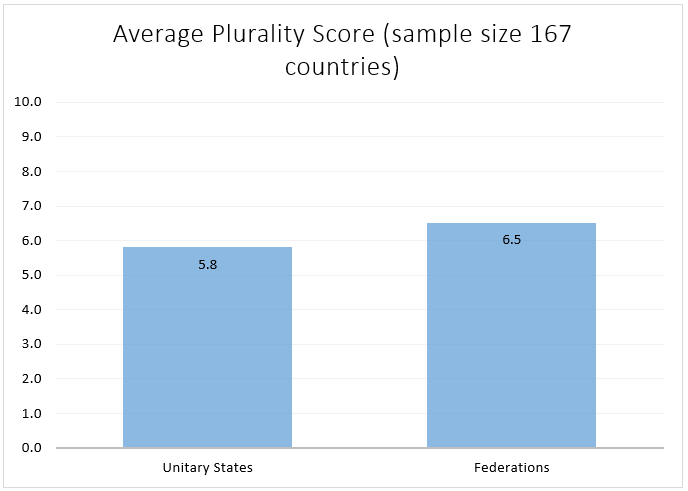

According to The Economist Intelligence Unit 2018 Democracy Index, federations on average have a greater score of plurality than their unitary state counterparts (see Figure 1 below), which can be used as an indicator of the spread of power in a country through decentralised structures.

However, despite federations on average being more decentralised, there are some notable exceptions. Russia is the world’s largest nation in land area, yet is highly centralised coming it at 132nd out of 167 in plurality ranking. Russia has moved to be more centralised in the latter part of Vladimir Putin’s presidency. Power is concentrated into the hands of the executive, and parts of the Russian electoral process is more a display of symbolism rather than it serving a real purpose. In 2000, Putin orchestrated the construction of seven federal districts above the regional level to increase central government’s power over these regions. To initiate constitutional change so quickly and centrally demonstrates that power has never been too far away from Moscow. There are notable divergent paths that both the UK and Russia have taken on the same political issue. With the rise of Scottish nationalism, the UK central government created the Scottish Parliament, as well as, granting an independence referendum. Russia, on the other hand, has brought in many centralisation policies under Putin to combat the rise of separatism in the Caucasus for example.

Even governments of countries considered to be highly decentralised, such as Spain, have their limitations. Spain is an example of a heavily decentralised unitary state that is often mistaken for a federation as a result, but it was not always that way. In Spain’s recent history was a nation that was very heavily centralised in the 1800s to the extent regional identity was not even recognised. After decades of civil unrest under Isabella II, led to a call for federalisation. Federalisation, however, resulted in chaos, and the framework to decentralise was constructed in a constitutional monarchy system. The central government has been hugely resistant to further decentralisation in recent times, most notably Catalonia’s attempt at self-determination is a shocking example of how a central government exerts its powers over regional governments. Despite the UK being so centralised, it didn’t display the level of paranoia that Spain’s central government displayed. The Scottish referendum is a powerful display of the UK’s willingness to look at a more devolved future rooted in democratic determinism.

The example of Australia is a swing in the opposite direction from Russia’s tightly squeezed states, in that, state determination and even to some extent territory government will determine all its own laws that aren’t covered by the national constitutional framework. On the democracy index, Australia scores a perfect score of 10 for pluralism, which comes as no surprise as the country is greatly decentralised to the extent that each state has its own constitution. The level of decentralisation is so high that each state also has its own executive, legislature and judiciary, similar to that of the federal institutions, and can pass any law so long it does not conflict with the Commonwealth as part of the Australian Constitution. Even the territories that do not possess full state-level autonomy exercise the right to some extent of self-government by the federal state.

France and Germany- differences in decentralisation for neighbours

France and Germany are fairly similarly decentralised in their own unique way. However, each country has been through very difference passage to decentralisation. Germany, reeling from WW2 and divided between the new emerging world hegemons quickly deconstructed the past and by 1949 had established a British parliamentary style setup with a Constitution and federal structure in the American style. Very quickly power was devolved and distributed, particularly to the courts who had the power to void law when deemed unconstitutional. Major areas of policy such as education and law enforcement became the responsibility of the states, a process which has taken much longer in other countries.

France, on the other hand, has been decentralising organically for over a hundred years and has kept its unitary state status. From around 1900 local authorities were recognised, but it wasn’t until 1982 when decentralisation was protected in law and then later to the Constitution in 2003. A country that started decentralisation much further back in time than Germany shows the huge differences each country takes in enacting this process. It is likely that when faced with a great crisis that causes a nation-state to completely rebuild itself- that this is the perfect opportunity to create a decentralised model very quickly.

Is the world becoming more centralised or decentralised?

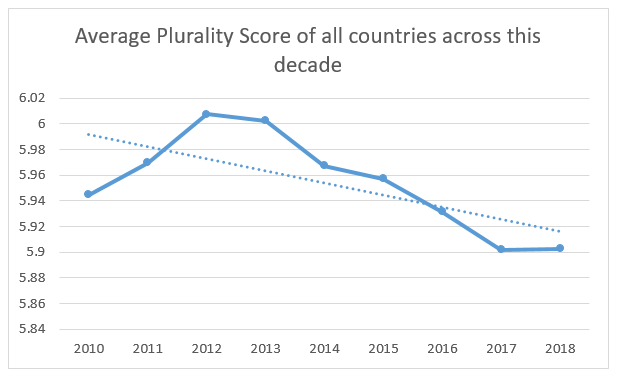

Taking the average plurality score from each yearly index, over the course of the decade seems to be in slow wane towards centralisation since 2012. Perhaps the trade war between President Trump and China or the events of the Arab Spring and Syria are contributory factors to governments increasing their grip on central control.

The future of decentralisation in the world is an unclear one. The level of centrality is likely to follow current global events that require interventions, conventions and action. The level of threats, opportunities or events that occur will determine whether a national or regional response is required. I can speculate that domestic events require regional action, but supranational events require the power of the centralised elites.

This blog was written by Josh Swan, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.