James Davies discusses his latest paper co-authored with Jon Morris and Gazi Islam. The paper examines the working lives of freelance television workers and the attraction of ‘meaningful work’ to increasingly precarious work conditions.

View the paper – Morris, Islam and Davies (2024) The search for meaningful work under neo-bureaucracy: Work precarity in freelance TV. Organization. 1-26

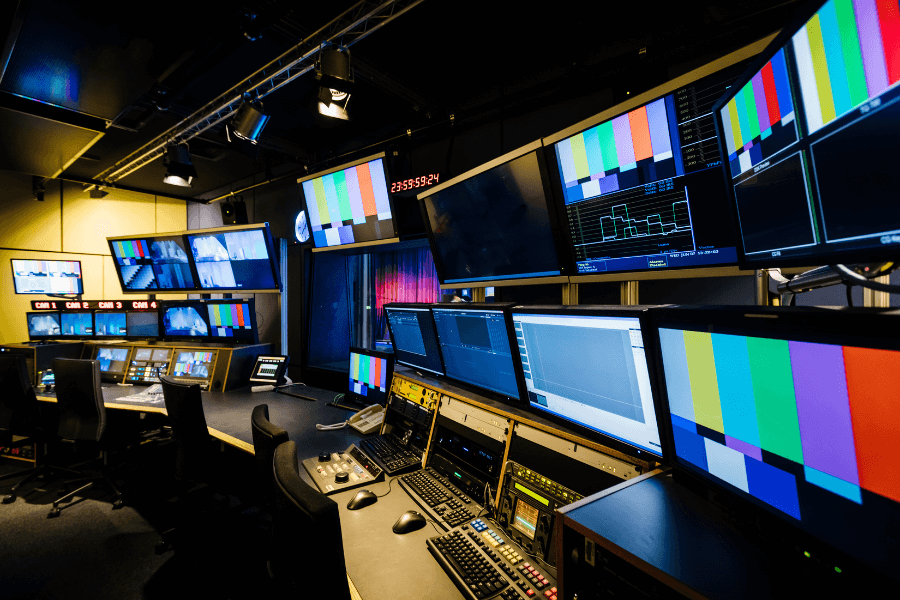

Work in Television has Changed Dramatically

The case of television production is unusual in a number of ways. It is both technical and artistic, a mainstream activity (Carter and McKinlay, 2013; Grugulis and Stoyanova, 2012), but positioned between industrial and artistic worlds, rather than a marginal ‘high-end’ form.

Over the past 30 years, TV production in the UK, and beyond, has transformed dramatically. Traditional structures were replaced by sector-level disintegration due to globalization, technological change, digitalization, and deregulation (Morris et al., 2016). State interventions have included creating Channel 4 with outsourced content, and the 1990 Broadcasting Act mandating the BBC to source at least 25% from the independent sector. Subsequent reforms accelerated the shift, favouring independent producers over in-house production (Carter et al., 2020). With much of TV production now outsourced, freelance work has become the norm (Work Foundation, 2019) with between 30% – 50% of the film and television workforce operating as freelancers on short-term contracts (OFCOM, 2019).

A Battle for Control

The television industry’s job market can be characterised as a battle for control:

- Large broadcasters have traditionally attempted to maintain control over the market by employing familiar faces on long-term freelance contracts.

- For freelancers, job markets have become increasingly precarious, especially for young or new workers who struggle to join the networks through which employment is negotiated.

- As broadcasters become less familiar with the freelancers, as older workers retire, they lose control.

- Insecurity often accompanies creative work, with a tendency to result in self-exploitation (Eikhof and Warhurst, 2013; Hoedemaekers, 2018).

Such tensions indicate the necessity of understanding these settings within the broader context of the creative labour process (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2011).

The Work Itself is a Form of Control

However, the quest for ‘meaningfulness’ may represent a new form of workplace exploitation. Despite numerous challenges, workers in precarious, intense, and uncertain conditions continue to pursue their artistic dreams. This persistence often places their passion for their work in conflict with the material demands of their lives. The ‘love of the job’ is used to offset increasing precarity and the absence of stable organizational support. There exists, among creative professionals, a notion that difficult work conditions are made acceptable by the significance of the work, which reinforces the idea that precarity is part of ‘the experience’ (Umney and Kretsos, 2015). In other words, the work is difficult, because it’s meaningful.

Most studies on meaningfulness overlook the external industry context that shapes this experience (Robertson et al., 2020). In modern fields like television, meaningful work blends creative self-expression with precarity (Petriglieri et al., 2019). Although some emphasize its emancipatory potential, empirical research reveals tensions: workers may find satisfaction in their work, yet suffer from negative aspects like poor conditions, job insecurity, and irregular employment, highlighting its ‘tensional’ nature (Symon and Whiting, 2019).

Modern TV production relies on social networks and reputational effects but is controlled by large producers who centralize strategy, decision-making, and resources. This can be seen as a ‘neo-bureaucratic’ structure (Morris et al., 2016): one that emphasises control without formal structural supports to minimise production risk, and contributes to the creation of a precarious workforce. Against the background of such structural changes, the search for personally meaningful work can be read as an attempt to recuperate dignity in the face of financial disadvantage and career instability (Boltanski and Chiapello, 2005).

Conclusion

This paper argues that ‘meaningfulness’ continues to attract new recruits, despite changes in production foundations. The concept of ‘meaning’ shifts with these contexts. While many studies focus on meaningful work as a personal relationship between workers and their labour conditions, our perspective examines how ‘meaningfulness’ evolves within neo-bureaucratic frameworks. The loosening grip of neo-bureaucracy may be disrupting television production, with major broadcasters trying to control the market by hiring familiar freelancers on long-term contracts, yet losing control as familiarity diminishes. At the same time, freelancers face increasingly precarious job markets, initially struggling to integrate into networks and finding work sporadic. As the television industry continues to evolve, questions remain about what attracts staff to an industry that promises meaningfulness but is also marred by precarity. Despite the intense pressures, new recruits remain drawn in by the promise of meaningful work.

This blog was written by Dr James Davies, Research Fellow at City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.