On the 6th April, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation released a report called “Raising productivity in low-wage sectors and reducing poverty“. The report was produced by Professor Anne Green and Dr Amir Qamar, City-REDI, University of Birmingham, Dr Paul Sissons and Dr Kevin Broughton, Centre for Business in Society, Coventry University.

On the 6th April, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation released a report called “Raising productivity in low-wage sectors and reducing poverty“. The report was produced by Professor Anne Green and Dr Amir Qamar, City-REDI, University of Birmingham, Dr Paul Sissons and Dr Kevin Broughton, Centre for Business in Society, Coventry University.

The report looks at the role productivity plays in employers’ wage-setting decision-making in low-wage sectors. It asks how employers think about, understand and measure productivity and what role productivity plays in employers’ wage-setting decisions among other factors. With the National Living Wage emerging as being of prime importance in wage-setting decisions, the key question is: How can productivity be improved to justify increases in wages?

The blog below, written by Dave Innes, Policy and Research Manager (Economics), JRF, provides a summary of the report.

Background

Productivity is on the national agenda. In recent years, policymakers have become increasingly concerned about two issues. The first is the UK’s productivity problem: that UK workers produce less per hour than their counterparts in France, Germany and the US. The second is its productivity puzzle: that productivity has flatlined over the ten years since the financial crisis.

Speaking at the 2016 Autumn Statement, Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond clearly stated the government’s belief that boosting national productivity holds the key to creating ‘an economy that works for all’:

‘It takes a German worker four days to produce what we make in five, which means, in turn, that too many British workers work longer hours for lower pay than their counterparts. That has to change if we are to build an economy that works for everyone. Raising productivity is essential for the high-wage, high-skill economy that will deliver higher living standards for working people.’

Tackling the UK’s productivity problem lies behind the government’s flagship Industrial Strategy. In the JRF’s response to the Industrial Strategy Green Paper, released in 2017, we argued the government has set themselves the right aim for a modern industrial strategy – building ‘a stronger, fairer Britain, that works for everyone’ – but that the Green Paper fell short of a set of actions that will achieve this goal.

The JRF argued that it is the lagging parts of the economy where Britain looks most different to its competitors: low pay sectors such as retail and hospitality, the long tail of low productivity firms, and the five million individuals in the UK lacking basic functional literacy and numeracy. A modern Industrial Strategy should focus on tackling these problems as well as a continual focus only on ‘shiny and new’ research, development and infrastructure.

The Industrial Strategy White Paper (Nov 2017), the latest iteration of the government’s evolving strategy, recognised that ‘some of the biggest opportunities for raising productivity’ come from low-wage, high-employment sectors, and promised to develop sector deals for hospitality, retail and tourism ‘to progressively drive up the earning power of people employed in these industries and enhance our national productivity’.

Over the past year, the JRF has commissioned three pieces of research (see Box 1) to inform what productivity strategies for low-wage sectors such as retail and hospitality should look like and whether driving up national productivity will bring about ‘an economy that works for all’. This paper presents a summary of our findings on three main questions:

- What role do low-pay sectors play in the UK’s productivity gap with other countries?

- Why is productivity in low-wage sectors lower in the UK than its competitors?

- Is raising productivity an effective way to combat low pay?

Box 1: This is a summary of three pieces of research, also published by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Forth, J. and Rincon-Aznar, A., ‘Productivity in the UK’s Low-Wage Industries: A Comparative Cross-Country Analysis’ Green et al., ‘Raising productivity in low wage sectors and reducing poverty’ Savona et al., ‘The heterogeneous wage distribution of labour productivity changes’

What role do low-wage sectors play in the UK’s productivity gap with other countries?

Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018) define low-wage sectors as those in which at least a quarter of the workforce earn less than 80% of the UK median wage[1]. The ten sectors in Table 1 together account for 38% of total hours worked in the economy, but only 23% of total value-added (as they are low-productivity sectors).

Retail and hospitality are particularly important given that they are large employment sectors with a high incidence of low pay. A little under half (46%) of workers in retail and just short of three fifths (59%) of workers in hospitality are low paid. The high incidence of low pay means that these sectors alone account for around a third of workers in poverty[2].

Table 1: The UK’s low wage sectors

| Sector | % on low pay | % of GVA | % of hours worked | Productivity (UK = 100) |

| Retail | 46 | 5.6 | 8.4 | 75 |

| Administrative and support services | 29 | 4.8 | 8.2 | 68 |

| Hospitality | 59 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 61 |

| Residential care and social work | 31 | 2.0 | 4.9 | 46 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 30 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 68 |

| Other service activities | 33 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 104 |

| Sale and repair of motor vehicles | 25 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 107 |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 38 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 43 |

| Food processing | 29 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 121 |

| Textiles and clothing manufacturing | 31 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 111 |

Source: Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018)

The UK is often compared to its competitors – especially the US, Germany and France – as a measure of the potential to improve UK productivity. So how do low-wage sectors compare? The authors use data from the EU KLEMS and adjust for cross-country, sector-specific price differences to compare productivity in these sectors across a set of 11 countries often considered to be the UK’s ‘competitors’.

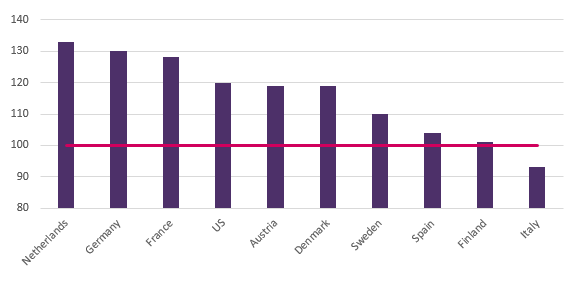

The authors find the UK’s productivity problem appears across all sectors of the economy, including low-wage sectors[3]. Of the comparison countries, only Italy had lower productivity than the UK in low-wage sectors (see Figure 1). The UK’s productivity gap with each of the US, France, Germany and the Netherlands ranges between a fifth and a third. German, French and Dutch workers in low-paying sectors produce more in four days than UK workers produce in five.

Figure 1: PPP-adjusted value-added per hour worked (UK=100)

Source: Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018)

Closing the UK’s productivity gap with its competitors in low-wage sectors could contribute substantially to overcoming the national productivity problem. Raising productivity in low-wage sectors to the levels in Germany, France and Netherlands would close between a fifth and a quarter of our productivity gap with them.

A second finding is that there is lots of variation in the size of the productivity gap across sectors and across countries. For example, the UK has similar productivity in retail to France and Germany, although productivity in the US retail sector is some 40% higher. Administrative and support services – a larger sector comprising services sold to businesses such as cleaning and security – are where some of the largest productivity gaps are found. Productivity in the French administrative and support services sector is 82% higher; in Germany, it is more than double the UK level.

Why is productivity in low-wage sectors lower in the UK than its competitors?

Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018) next decompose the UK’s productivity gap in low-wage sectors into the contribution of relative capital intensity, relative labour quality and relative ‘Total Factor Productivity’ (TFP). TFP is the part of the productivity gap that can’t be explained by differences in capital intensity or labour quality. It is an indicator of the differences in the efficiency of the production processes between two countries. TFP could be influenced by many other factors, which are discussed below.

While there are differences across sectors and across countries, there is, in general, a pattern that weaknesses in UK productivity are attributable primarily to differences in TFP, followed by differences in labour quality, with differences in capital intensity playing a more minor role.

To demonstrate the point, Figure 2 shows the decomposition of the UK’s productivity gap with the competitor with the highest productivity in four key low-wage sectors. In each case, TFP contributes the majority of the total productivity gap. Labour quality is the second most important factor in retail and hospitality, although in the other two sectors actually contributes to closing the gap as the UK has higher measured labour quality.

Figure 2: Contribution of capital intensity, labour quality and TFP to the UK’s productivity gap with the international sector leader

Source: Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018)

This finding begs the question ‘what explains differences in TFP across countries?’ As TFP is a measure of how efficiently labour and capital are used to produce economic output, there are a broad number of factors that could affect TFP. The research next looks at which of these factors are associated with higher TFP across sectors and countries.

The research finds that TFP is higher in countries and sectors with:

- A higher proportion of workers in training;

- Better management practices, such as the use of performance related pay;

- A higher percentage of workers using ICT;

- A lower share of temporary workers; and

- With less product market regulation.

The analysis points towards a set of factors which could serve as a focus for efforts to bring about improvements the UK’s relative TFP performance in low-wage sectors in the future.

Is raising productivity an effective way to combat low pay?

The quote from Philip Hammond in the introduction demonstrates the government’s belief that raising productivity holds the key to improving living standards. It is widely agreed that in the long run national productivity is the key determinant of a country’s living standards. Two research projects considered whether the same is true at the firm and sector level. Would improving productivity in low-wage sectors and low productivity firms drive up wages for low paid workers?

Green et al. (2018) look at this question using a survey and interviews with employers in the West Midlands. The first finding from this research is that many firms have only a partial understanding of what productivity means and have considerable difficulty measuring it. This provides a substantial challenge to policymakers trying to encourage these firms to boost productivity.

Through the survey, several firms said that productivity was important in setting wages, but few in the interviews could describe how. Bigger concerns to firms in setting wages were the local availability of staff and retaining labour, while local and sector pay norms were also important. A picture emerges of most firms being ‘price takers’ when it comes to labour – generally they set wages at a level necessary to recruit and retain staff but no higher, and they don’t set wages either to encourage or to reward higher productivity. Staff rewards were more likely to be used to reward productivity.

Similar themes emerged from quantitative work by Savona et al. (2018). This research merged data on employees from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings and business data from the Annual Business Survey, to examine the effects of increases in firm and sector productivity on wages.

Overall, the research provides little evidence of a strong relationship effect of increasing productivity at either the firm, sector or local labour market area level on wages in the period 2011 to 2015 (see Table 1). Looking across all sectors, an increase in firm productivity is associated with an increase in wages, but the effect is tiny: a 10% increase in productivity increased wages by just 0.05%.

There is some evidence of a larger effect of sector productivity on wages in some industries, but the effect is still small. In construction, where the largest effect is found, a 10% increase in productivity is estimated to bring about a 1.7% increase in wages.

The research also looked at whether this relationship is different for different types of workers but found that, overall, there is little evidence of large effects of changes in productivity on wages for any wage level or age of workers.

Table 2: % change in wages from 10% increase in productivity (2011 to 2015)

| Firm | Sector | |

| Manufacturing | -0.02 | 0.04 |

| Construction | 0.02 | 1.73*** |

| Wholesale & retail | 0.07*** | 0.37* |

| Hospitality | 0.08 | 0.56 |

| Transport | -0.00 | 0.37 |

| Finance | 0.11 | -0.75 |

| Business Services | 0.05 | -2.04*** |

| Other | -0.00 | -0.32 |

| Overall | 0.05*** | -0.38*** |

Source: Savona et al. (2018) Notes: [1] All regressions include year dummies and individual controls: age dummies, tenure in current job, a dummy to identify switch to full time job. [2] We use robust standard errors and statistical significance follows the system: ***1%, **5% and *10%.

The results should be read with caution, as the period studied was far from normal for the economy, with both productivity and wages undergoing a very slow recovery. Studies in different countries have normally tended to find a stronger relationship between productivity and wages, with bigger effects on sector productivity than firm productivity[4]. A much earlier study in the UK found that a 10% increase in firm manufacturing productivity increased wages by 2.9%[5].

Improvements in productivity could come from different sources, and it may be that the way that productivity is improved affects the relationship between productivity and wages. While the research was not able to look at this issue, focusing on productivity improvements to do with how well we use the potential of workers in low-wage sectors – such as those suggested as being most important to close the UK’s productivity gap with its competitors above – may be the types of productivity improvements most likely to benefit workers.

The National Living Wage

Many firms interviewed by Green et al. (2018) said that they felt wage setting had been taken out of their hands by the introduction of the National Living Wage; for many, this has become the de facto wage floor. The increase in labour costs they were facing, as a result, had been a spur for them to think about how to improve productivity to avoid a hit to their profits. The research adds to other evidence which suggests that raising of the wage floor has been an effective way to increase both wages and productivity[6].

Policy lessons

From the research the JRF has conducted, it is clear low-wage sectors matter for the UK’s national productivity. Boosting productivity in sectors such as retail and hospitality could play an important role in creating ‘an economy that works for all’. Raising productivity in low-wage sectors to the levels in Germany, France and Netherlands would close between a fifth and a quarter of our overall productivity gap with them.

The UK’s productivity gap with its competitors in low-wage sectors is not due to a lack of capital investment or workers’ formal skills but how well we use workers in these sectors. This finding fits with previous JRF work that found that the majority of low-wage retail workers feel overqualified for the work they do[7]. There is significant potential to increase productivity if people are given the opportunity to perform at the level of responsibility that they feel capable of.

To improve productivity in low-wage sectors such as retail and hospitality, the research suggests government and businesses should focus on improving how well we use workers by:

- Boosting the proportion of workers in training;

- Improving Management practices;

- Increasing the use of ICT; and

- Reducing the share of temporary workers.

Creating an economy that works for all will, however, need more than a focus on improving productivity in low-wage sectors and firms, as there is no guarantee higher productivity will be passed onto workers as higher wages. Improving productivity in low-wage sectors needs to be complemented by other policies to make sure workers see some of the benefits. Productivity improvements that allow workers to utilise their skills and so work to their full potential are likely to benefit workers most.

Workers are also more likely to see wage rises when productivity is improved across a whole sector than just in their own firm. Policy is, therefore, best focused on diffusing productivity improvements to the long tail of low productivity firms than further improving productivity among market leaders.

Footnotes:

[1] 80% of the UK median hourly wage was £7.20 in 2015.

[3] One previous study (Spencer et al. 2016) found that the UK’s productivity gap with its competitors is larger in low-wage sectors than the rest of the economy. Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018) come to a different conclusion. It does not necessarily disprove the results of the previous study but highlights the importance of methodological choices in making these comparisons. Two important differences are that this Forth and Rincon-Aznar (2018) takes a broader definition of low-wage sectors (including the ‘other service activities’ sectors) and adjusts for sector-specific price differences across countries.

[4] Card et al. (2018), ‘Firms and Labor Market Inequality: Evidence and Some Theory’.

[5] Van Reenen, J., “The Creation and Capture of Rents: Wages and Innovation in a Panel of U. K. Companies,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, feb 1996, 111 (1), 195–226

[6] Riley, R and Bondibene, C. (2015) ‘Raising the standard: Minimum wages and firm productivity’ NIESR Discussion paper No.449

[7] Ussher (2016), ‘Improving pay, progression and productivity in the retail sector’.

This blog is by Dave Innes, Policy and Research Manager (Economics), JRF and was first posted here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.