Dr Magda Cepeda-Zorrilla investigates the adoption of electric vehicles in the UK alongside the government’s plans for net zero, and the challenges that the owners of electric vehicles face.

This article was written for the Birmingham Economic Review.

The review is produced by City-REDI / WMREDI, the University of Birmingham and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce. It is an in-depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and a high-quality resource for informing research, policy and investment decisions.

Global warming and fossil fuel shortages are two main problems that the UK government can address with the net-zero carbon policy. This policy has set 2030 as the deadline for the end of new petrol and diesel car sales, alongside the increase in the production and consumption of electric vehicles (EVs) in the UK. With this, the UK will be on course to be the first G7 country to decarbonise cars and vans (see GOV.UK news story).

The electric car market is growing steadily. In terms of business growth, according to a Tracxn report, there are 18 electric vehicle start-ups in Birmingham, and by June 2022 there were 1.8 million electric vehicles in Britain (see Jackman, 2023).

Data shows that by the third quarter (July to September) of 2022, 14% of new car registrations in the UK were battery electric vehicles (BEV) with a further 5% being plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV), of which the average CO2 emissions for vehicles registered for the first time in the UK decreased by 1% in 2022 third quarter compared to 2021 third quarter (see GOV.UK vehicle licensing statistics).

One of the short-term challenges for electric vehicle owners and the UK Government is the shortage of charging infrastructure. The ratio between EVs and charging infrastructure is essential and plays an important role in facilitating the use and ownership of EVs. Diverse reports and studies have consistently shown that the lack of infrastructure provision is a concern for many consumers and is a key barrier to mass uptake. Therefore an efficient and sustainable charging infrastructure network is essential to achieve the transition to electric vehicles.

Norway, for instance, has the largest number of EVs on the roads. These account for more than 20% of passenger vehicles in the country and more than 80% of new vehicles sold. To date, they count on more than 22,000 public chargers to service the more than half a million EVs on the roads.

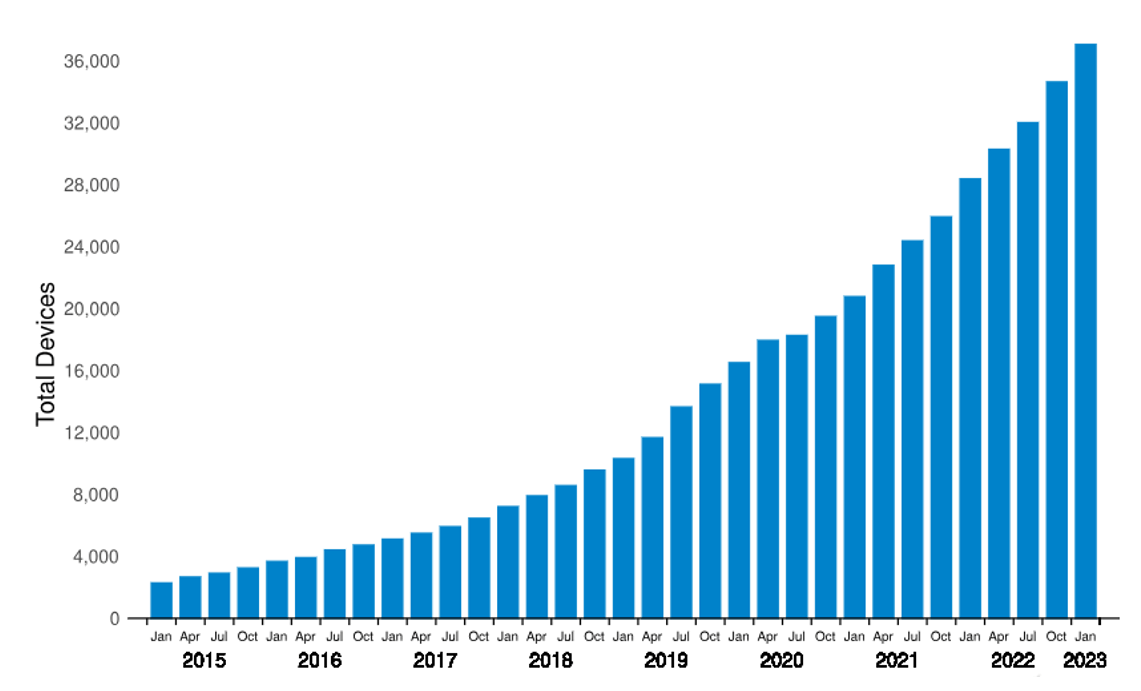

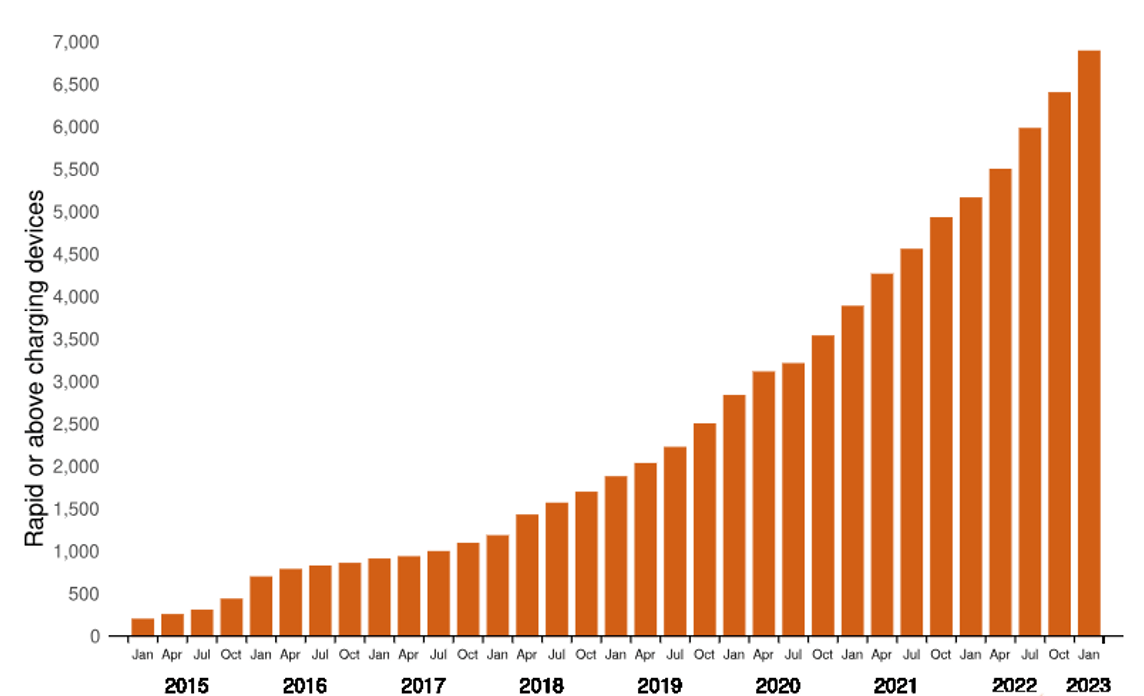

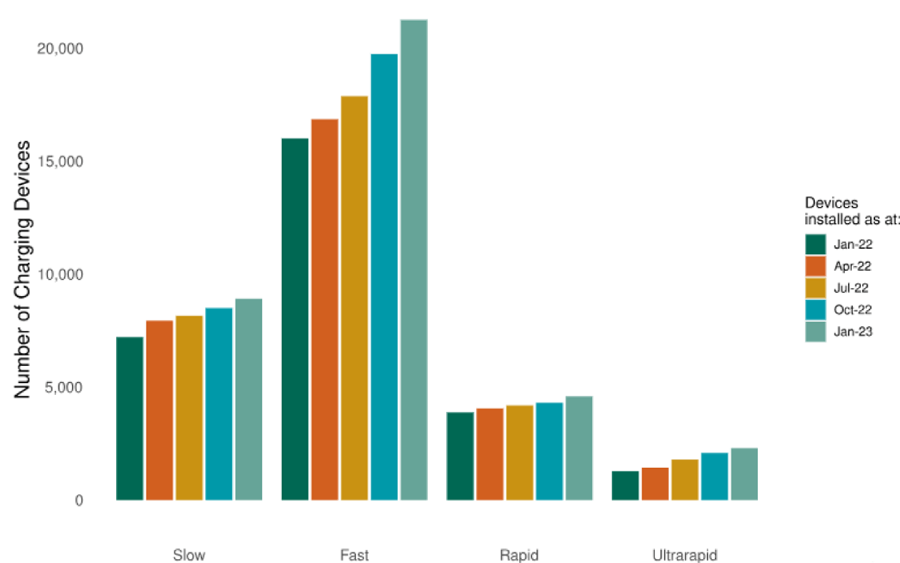

The charging infrastructure in the UK started in 2011 and in Figures 1 to 3 we can see that although there has been a sustained increase in the installation of chargers, the big increase has been for slow and fast charging, rather than the rapid and ultra charging, which makes a difference for people spending longer to charge their vehicles. To compare the four charging speeds, we can see that the Slow Charging Devices represent 3 kilowatts (kW) to 6 kW; the Fast-Charging Devices represent 7kW to 22kW; the Rapid Charging Devices represent 25kW to 100kW and the Ultra Rapid Charging Devices represent 100kW plus.

Figure 1: Installed UK public charging devices, midnight, 1 of month, since 2015

Source: DfT. 2023. Electric vehicle charging device statistics: January 2023 (table EVCD_02)

Figure 2: UK public rapid charging or above devices, midnight, 1 of month, since 2015 (table EVCD_02)

Source: DfT. 2023. Electric vehicle charging device statistics: January 2023 (table EVCD_02)

Figure 3: Public charging devices by charging speed, since 1 January 2022

Source: DfT. 2023. Electric vehicle charging device statistics: January 2023 (table EVCD_02b)

In the UK there are currently 31,476 charging connectors at 11,274 locations – the majority (25%) of these are in Greater London. In the West Midlands, there are charge points at car parks and the following train stations: Bromsgrove, Longbridge, Solihull, Rowley Regis, Tile Hill and Yardley Wood.

The UK government recognises that a focus on vehicles is only half of the challenge to delivering net zero road transport. Charging infrastructure is essential, and the plan is that by 2030, there will be a minimum of at least 300,000 public charge points in the UK.

Although EVs can help to achieve net zero by 2030, to achieve the targets for 2050, researchers have stated that the target requires more than just using electric vehicles, it requires also reducing the distance travelled and consistent investment in active travel.

Moreover, we cannot ignore the fact that EVs are not the solution to other social and environmental problems. By reviewing empirical research, we can conclude that although EVs can help in delivering Net Zero road transport, these vehicles do not contribute to a sustainable future for different reasons.

One reason is that they do not contribute to reducing traffic congestion. According to the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA), 62% of people in the West Midlands said they were dissatisfied with current congestion levels. A report from the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce stated that in the region, 41% of journeys of less than 2 miles are undertaken by car (whereas the national level is 38%). Birmingham is the third most congested city in England, where motorists in the city spend 9% of their total journey time in traffic congestion, costing the city £407 million in lost revenue and on average, £990 for each driver.

On the other hand, research shows that “battery production significantly impacts the environment and resources, and battery materials recycling and remanufacturing present considerable environmental and economic values”. In fact, according to research, the greening of electricity is critical to reducing carbon emissions during the battery life cycle.

This blog was written by Dr Magda Cepeda-Zorrilla, Research Fellow, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.