On 11 November 1918, the war to end all wars, World War 1, ended with the signing of the armistice. The next day, David Lloyd George, then UK prime minister, called a general election promising that the government would provide “habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war”. This became known as the “homes fit for heroes” speech. The election was a landslide victory for David Lloyd George’s coalition government.

On 11 November 1918, the war to end all wars, World War 1, ended with the signing of the armistice. The next day, David Lloyd George, then UK prime minister, called a general election promising that the government would provide “habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war”. This became known as the “homes fit for heroes” speech. The election was a landslide victory for David Lloyd George’s coalition government.

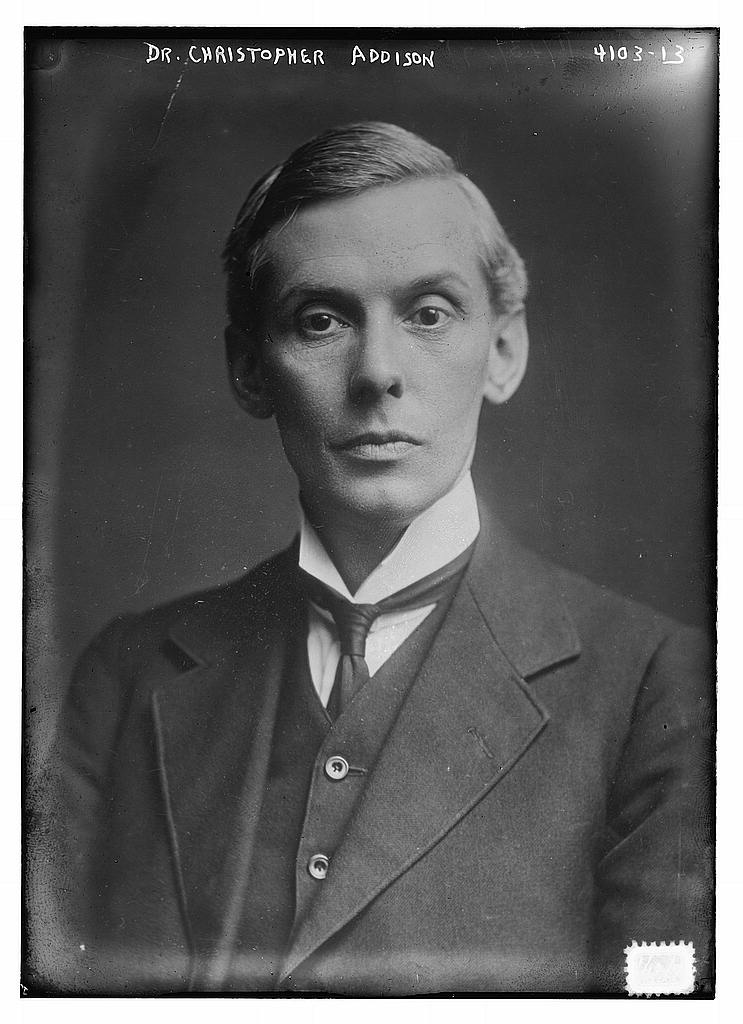

On 31 July 1919, the Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919 passed onto the statute books. This act amended the law related to working-class housing, town planning and the acquisition by local authorities of smaller dwellings. This act became known as the ‘Addison Act’ after its author, Dr Christopher Addison, the Minister of Reconstruction and then of Health. Lloyd George was concerned with the emergence of Bolshevism and Revolution; state expenditure on new homes, each with a garden surrounded by trees and hedges, was considered as an insurance policy against social unrest. The Act imposed a duty on every local authority to survey housing needs and to make and carry out plans. It guaranteed a state subsidy. The Addison Act was the start of a long tradition in the UK of housing provided by the state for the people.

On the 100th anniversary of the Addison Act, it is important to reflect on the importance of this legislation and the role it played in transforming the life experiences of soldiers returning from the battlefields. This act is one of the beacons in the development of UK housing policy. But, like most policies, it was only partially effective.

Today, housing provision remains a major challenge for the UK. These challenges include affordability, availability and accessibility. In the UK, housing is considered as an investment asset rather than a social asset. As an investment asset households’ fix wealth into a property on the understanding that they will benefit from an escalation in capital values. The resulting distortions produce localised skill shortages as key workers, teachers, nurses, firefighters, are unable to rent or buy.

Housing plays an important role in economic development as availability and affordability shape local economic outcomes. Linking housing provision with local employment opportunities would reduce commuting times, carbon emissions and enhance the quality of everyday living.

Ideally, every UK city-region should have an integrated housing strategy that is a core part of a local industrial strategy. At the moment, this is impossible. Housing provision in the UK can be considered to be a classic case of public and private sector failure and of the siloed nature of policy development. An integrated approach to housing provision would link housing with employment opportunities and public sector services. It would also capture escalations in land value derived from public sector investments to finance public services. Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway (MTR) applies land value capture (LVC) to create a financially sustainable business model. Increases in land value, derived from MTR investments, are captured to finance the continued development of the mass transit system. This is an excellent example of an integrated approach to housing, transportation and economic development.

For the London Underground, this additional value has been predominantly gifted to the private sector. The first London underground line, the Metropolitan Line, was opened between Paddington and Farringdon in 1863. The underground was built and run by private sector companies who had great difficulties attracting investment and in running the system for profit. The Metropolitan Line survived as a separate company until the creation of London Transport in 1933. This survival was based on the Line’s ability to exploit its land resources around its stations. The Metropolitan promoted housing estates adjacent to the railway under the “Metro-land” brand with nine housing estates constructed near its stations. The Metropolitan acquired the rights to grant building leases, to sell ground rents and to develop its own housing estates. This included extensive developments in London’s suburbs. In 1925 a retail development was constructed with 180 flats above Baker Street station with capital costs of £500,000 for an annual rental income of £40,000; a higher return on capital than could be made from running the railway line.

For the London Underground, this additional value has been predominantly gifted to the private sector. The first London underground line, the Metropolitan Line, was opened between Paddington and Farringdon in 1863. The underground was built and run by private sector companies who had great difficulties attracting investment and in running the system for profit. The Metropolitan Line survived as a separate company until the creation of London Transport in 1933. This survival was based on the Line’s ability to exploit its land resources around its stations. The Metropolitan promoted housing estates adjacent to the railway under the “Metro-land” brand with nine housing estates constructed near its stations. The Metropolitan acquired the rights to grant building leases, to sell ground rents and to develop its own housing estates. This included extensive developments in London’s suburbs. In 1925 a retail development was constructed with 180 flats above Baker Street station with capital costs of £500,000 for an annual rental income of £40,000; a higher return on capital than could be made from running the railway line.

The Metropolitan’s approach to LVC was innovative but ended with the nationalisation of London Transport. This LVC approach highlights the advantages of developing an integrated approach to local economic development.

One of the limitations of the Addison Act was that its focus was on housing rather than the development of an integrated approach to local economies. Housing is too often isolated from local economic development and is seen as distinct from skills and industrial strategies. This is unfortunate. It is timely, for the UK to develop an integrated approach to local economic development that prioritises the provision of high-quality residential living as part of a longer-term approach to the development of place-based industrial strategies.

This blog was written by Professor John Bryson, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.