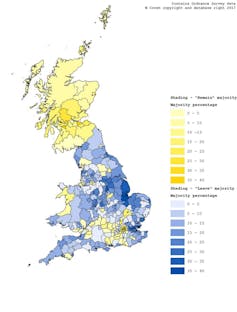

The very areas of the UK which voted Leave in June 2016 are likely to be the ones hardest hit by Brexit. Our research on the likely economic consequences of leaving the European Union on different regions and industries is consistent with the recently leaked government analysis which suggests that London will be one of the areas least hit in the event of a no-deal Brexit. The north-east of England, meanwhile, will be one of the worst affected.

An important element here is that these regions (and the sectors of the economy based there) have little representation in the Brexit negotiations and rarely figure in media discussions. When it comes to the potential impact of Brexit, the most prominent stories are those with underlying political or business interests. For example, the case for special treatment of particular industries after Brexit tends to revolve around financial services, automobile and aerospace firms.

On the one hand this is because these industries are widely understood as critical for the UK economy. But it’s worth noting that these industries also have strong lobbying power and access to government policymakers. In contrast, many other parts of the UK economy do not. Our analysis suggests that, in reality, it is many of the less high-profile sectors – and the regions where they are located – that could be the most exposed to Brexit.

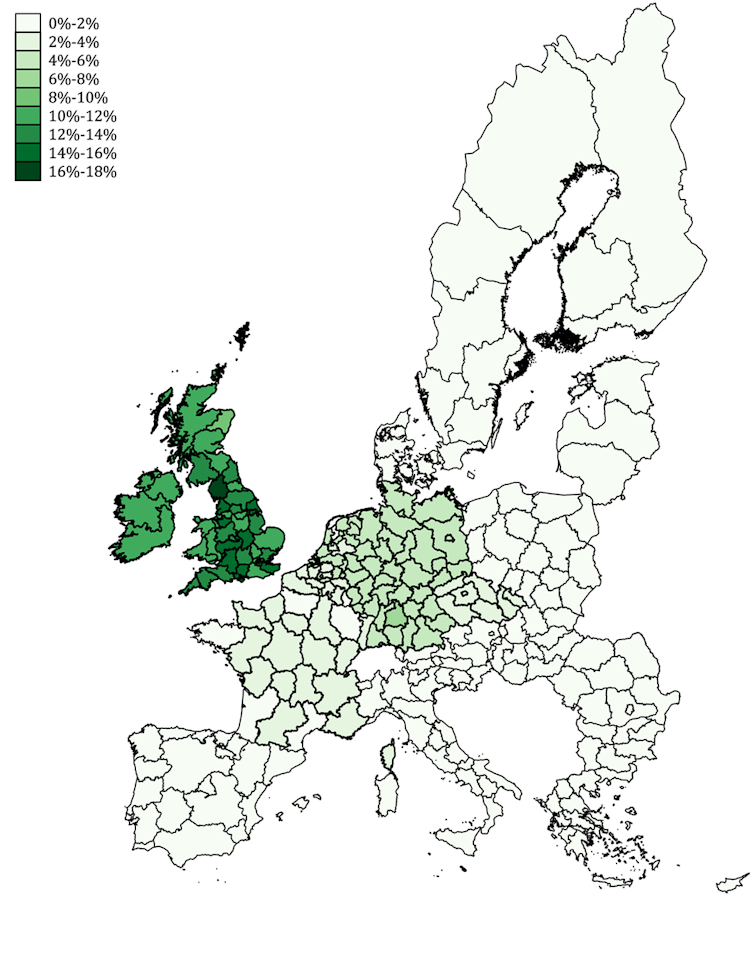

We examined the extent to which British industries depend on trade with the EU. On the basis of an analysis of global trade patterns across 43 countries and 54 industries, we were able to calculate a Brexit risk-exposure index.

We did this for each UK sector under a “no deal” Brexit scenario in which much of UK trade faces severe disruptions and impediments. We also put together a “hyper-competitive” scenario in which UK industries can rapidly adapt and mitigate against the effects of losing single market access.

In our analysis, an industry’s exposure to Brexit is defined by the extent it is dependent on products or services that cross a UK-EU border at least once. We calculated exposure levels for different industries. They indicate how much the industry has to restructure its supply chains and employees to mitigate against the losses caused by reduced post-Brexit trade and movement with the EU. This gives us a picture of which industries are likely to be hit hardest by a no-deal Brexit and which ones will most likely remain virtually unaffected.

Deal or no deal

Across the UK, the results for a no-deal Brexit scenario show:

- More than 2.5m jobs are directly at risk.

- Almost £140 billion of UK economic activity annually is directly at risk.

- Many important manufacturing and primary industries are at risk, but so are many service industries – not just financial services.

- Many of these services are not only exported directly to EU countries, but are also sold to UK manufacturing firms who then export to the EU.

- Workers in the jobs at risk are on average slightly more productive than the average British worker – so Brexit is likely to exacerbate the UK’s productivity problems.

The findings show that in 15 out of 54 industries, more than 20% (and up to 36%) of economic activity is at risk from Brexit. Industries include fisheries, chemicals and motor vehicle manufacturing.

The industries facing the highest risks overall, and likely to be the hardest hit by a no-deal Brexit, are service industries such as professional, scientific, administrative and technical services. Others at high risk include the wholesale trades, legal and accounting services, retail trade, warehousing, land transport services, computer programming, and activities that support financial services. These are all industries which are dissipated across the wider economy and have very little structured lobbying power or media profiles.

Alternatively, in a “hyper-competitive scenario” – where UK industries can rapidly adjust to life outside the single market by sourcing parts in the UK that are currently sourced from the EU – our findings suggest that increases in UK employment and GDP could be about one-third of the losses in a no-deal scenario. So the risks for the UK would be much less in this scenario.

But current UK productivity figures suggest that most of the UK economy is nowhere near being hyper-competitive, so this case appears to be largely unrealistic.

Sector and region inequality

Our research also found that financial services is one of the least vulnerable sectors to Brexit with an exposure level of 8% of its GDP being at risk. This is still significant, but it is low in comparison to many other sectors – largely because the financial services sector is already highly globalised and therefore displays a low dependence on EU markets.

Instead of financial services, greater emphasis should be placed on helping other, much more exposed sectors. Those that are likely to be the hardest hit by a no-deal Brexit are a range of other services industries. But these are parts of the economy which don’t lobby Westminster and rarely get the attention they need.

Our other analyses also show that it is the Midlands and the North of England which are by far the most vulnerable. They are more exposed to Brexit than any other region in Europe. The reason is that the Midlands and north of England are much more dependent on EU markets for their trade than London, the South-East or Scotland.

As such, in the UK-EU negotiations there is no real representation from either the most exposed sectors or the most exposed regions. Instead, the focus of government discussions tends to be on those sectors and regions which are actually the least exposed parts of the UK economy. This means that whatever is finally negotiated is unlikely to alleviate the effects of Brexit on the vast majority of the UK.

![]() This article was published in conjunction with the UK in a Changing Europe initiative. Wen Chen, Bart Los, Mark Thissen and Frank Van Oort were co-investigators on the research mentioned.

This article was published in conjunction with the UK in a Changing Europe initiative. Wen Chen, Bart Los, Mark Thissen and Frank Van Oort were co-investigators on the research mentioned.

Raquel Ortega-Argilés, Chair in Regional Economic Development, City-REDI, University of Birmingham and Philip McCann, Chair in Urban and Regional Economics, University of Sheffield

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.