We all think we know the internet right? It’s a vast playground where the very good and the very bad can occur. It’s an environment where political debate, memes, and likes all form the cohesion of discourse online. Yet I would dare say we don’t know the real impact the internet is having today on humanity. We can gather as much data as we like, but when we put the pieces together to see the bigger picture, it will be too late to react.

We all think we know the internet right? It’s a vast playground where the very good and the very bad can occur. It’s an environment where political debate, memes, and likes all form the cohesion of discourse online. Yet I would dare say we don’t know the real impact the internet is having today on humanity. We can gather as much data as we like, but when we put the pieces together to see the bigger picture, it will be too late to react.

Good or Bad?

Most notably the internet is being blamed for polarisation over the Brexit Election, as well as, various other political topics. Evgeny Morozov, a Belarus/American writer for Stanford University wrote: “The Internet is like money; you cannot identify its good or evil in general as it already forms part of society and it will depend on the individual conditions”. He goes on to state that there is no right and wrong view on many matters, such as the 2011 Arab Spring and the role of social media. On the one hand, supporters state how effective social media was a mobilising millions of people to topple kleptocratic and autocratic regimes. The counterview states the internet was a bad thing in the Arab Spring as it led to more surveillance and paralysis of the masses after the first wave of protests. The online debating arena doesn’t produce a clear winner, but instead a political ping-pong match of points that goes on endlessly with no conclusion. Evgeny determined that often it is common for both opposing parties in the debate are simultaneously right and wrong.

The result of the continuous road of debate and no destination in sight has vastly changed how we live our lives and our values. Tribal groups have emerged that seek to consistently oppose its political opposites, and there is no true place of this apparent reality than in the realm of Twitter. The last decade defined the rise of “a revolution in politics is underway… being fought 140 characters at a time”. Politicians tweet the agenda and journalism then rush to cover what has been said. Furthermore, the role of social media such as Twitter and Reddit has thrust a previously passive audience into an opinion-centred culture which becomes a feedback loop.

The very notion that we can be in touch with anyone in the world and hear anybody’s thoughts ironically creates a sense of disconnectedness. Never before has the world been so intertwined in a cyber-nexus of human interaction, but this interaction has been diluted and confined to a small light-up rectangle, instead of a human face. In effect, because we are suffering from what Marshall McLuhan predicted over 40 years ago when “augmentation leads to amputation”. Formerly, if an individual wanted to disconnect from media they could do so quite easily, but since the coming of the “Global Village”, privacy is now a premium commodity, its worth driven up by its diminishing supply. The result of the powerful forces of hyperconnectivity and activism colliding terraforms the political climate into vast polarised tribes, in constant suspicion and disgust of one another 24/7. Studies on the United States show that in a 22 year period from 1994, party affiliates’ view of the other party was “very unfavourable” was at 20% but had risen to 55% in 2016.

A Divided Climate

A Divided Climate

What is causing this spike in political polarisation? Polarisation has certainly happened before in the 60s and 70s in America. Unlike those times, however, never has the level of discontent been so publically displayed for the world to see as passive political individuals have transitioned into vocal activists. What happens in America ultimately filters into UK politics as well whether it is the Presidential style that was Blair’s premiership, the rise of television debates, establishment of a separate judiciary named the Supreme Court or even “#fakenews”, it shows how susceptible we are to the political climate across the pond. A theme around the rise of fake news has been the view that social media sites are “echo chambers” that place individuals in safe-space environments where increasingly all their social interactions are with people who believe and tweet the same thing. The algorithms are the rudder and the sail of political debate as it drives and steers individuals into their preferred harbour of political preference. This is a problem for politics as the role of the internet categorises people into different thinking camps, and then creates an anarchic arena for these vast swathes of individuals to shout and taunt each other from the safety of their somewhat online anonymity. Social media platforms amplify emotive messages which make their message more radical, and before long regular exposure to an opposite political opinion drives you towards polarisation of your own political leanings. When the algorithms of the internet place us in these safe spaces of filtered political rhetoric, the polarisation effect that occurs makes consensus building much less likely across the political structure, which is hugely problematic for democratic nations that are supposed to respect the outcome decided by the majority and unite to make the nation whole again.

Political Advertising

The extent of polarisation and allegations of political foul play has impacted how political advertising campaigns are conducted across nations. Twitter recently banned political ads, possibly due to the catalytic story of Russian hackers infiltrating the US Presidential election and possibly the Brexit referendum in the UK. Still, this has not stopped twitter users retweeting screenshots of their chosen political candidates in an effort to shout louder than their opponents and to appeal to their political tribes. Tim Berners-Lee, the architect of the World Wide Web, has spent much of his time in the last 30 years thinking and speaking about how to protect the invention he created. His concern lies around ad-based revenue models that reward clickbait and the viral spread of misinformation. This points to a post-truth world that is more concerned with getting its voice and opinions heard over the truth, which people are unsure of what truth even is anymore.

Conclusion

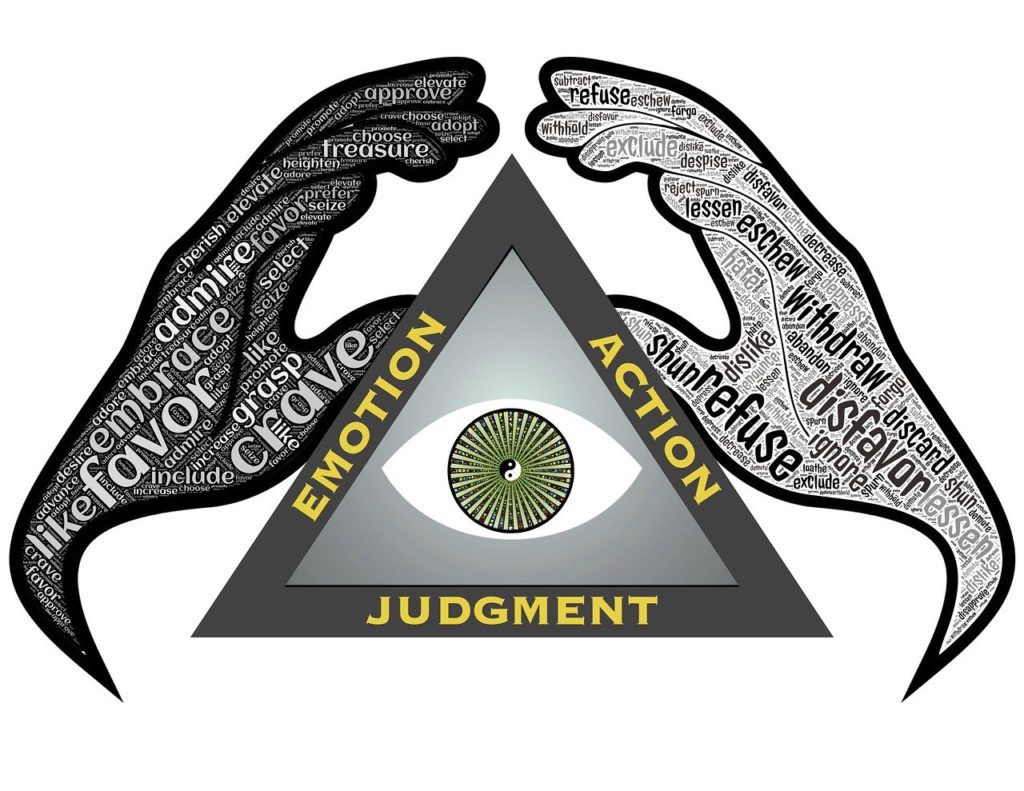

Earlier I referenced that the internet is a lot like money, in that a lot of good or evil can be achieved through its means, but the debate on whether the entity is good or bad in itself is not something that has been concluded. Perhaps it is wrong to think of the internet as ‘Good’, ‘Bad’ or even just a bit of both. Perhaps it’s more of a case of a fine line between order and chaos; too much of one strikes imbalance in the system. We live in a time of a new political arena that belongs at the supra-national sphere of affairs and to the likes of which, remains uncertain. Political discourse has polarised, grouped and fractured member states into different political camps. Truth is no longer at the forefront of peoples’ minds, emotions are more and more becoming how people think and ultimately how we should design policy. Political discourse is messier than ever, thanks to the rise of the internet and the death of the passive individual. Action must be taken in order to prevent further exacerbation of the symptoms felt in every corner of public debate.

This blog was written by Josh Swan, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.