Professor Anne Green examines education, work, health, ethnic and generational inequalities in the West Midlands before and after the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

Professor Anne Green examines education, work, health, ethnic and generational inequalities in the West Midlands before and after the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

Introduction

In 2019 the Nuffield Foundation funded a major study, chaired by Sir Angus Deaton, to assemble the evidence on the causes and consequences of different forms of inequalities, and the ways that they can best be reduced or mitigated. An Introduction to the IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities, published in May 2019, contended that concerns about inequality should not just cover income, but should encompass themes such as health, wealth, political participation, and also opportunity, by gender, ethnicity, geography, age and education, and how key forms of inequality relate to each other. Through a series of thematic analyses, the Review has set out to examine the big forces that drive inequalities – from technological change, globalisation, labour markets and corporate behaviour to family structures and education systems.

A study on geographical inequalities in the UK, entitled Catching up or falling behind? Geographical inequalities in the UK and how they have changed in recent years highlighted that:

- Regional inequality is not increasing for incomes, but it is for wealth

- Local inequalities are significant

- Former industrial areas in the Midlands and North and coastal towns have not been falling behind but have become poorer

In 2020 the Covid-19 crisis brought inequalities to the forefront of popular and policy attention. As summed up in a New Year’s Message from the Deaton Review of Inequalities (pages 10-11) published in the first week of January 2021:

“This has been a year in which many inequalities have been exacerbated. Poor children have been hit worse than their better-off peers. Higher earners and graduates have had their work disrupted much less than lower earners and the less highly educated. The poor, and ethnic minorities, have borne the brunt of the health crisis. And the young have suffered a much bigger economic hit than the middle-aged, while the old – who, of course, have been most at risk from the virus – have been largely insulated from the awful economic shock.”

Selected key issues from analyses regarding education, work, health, ethnic and generational inequalities are outlined below, with key implications for the West Midlands identified.

Education

It is timely to examine educational inequalities given the closure of schools in the first week of January 2021 and so these are examined in most depth. The West Midlands metropolitan area has a higher share of the population in school (and pre-school) age groups than across England as a whole.

There were marked educational inequalities before the Covid-19 crisis. For example, about 40% of pupils on free school meals getting good GCSEs in English and maths compared with around 70% of other pupils. The West Midlands – and especially Birmingham – has more pupils on free school meals than the national average.

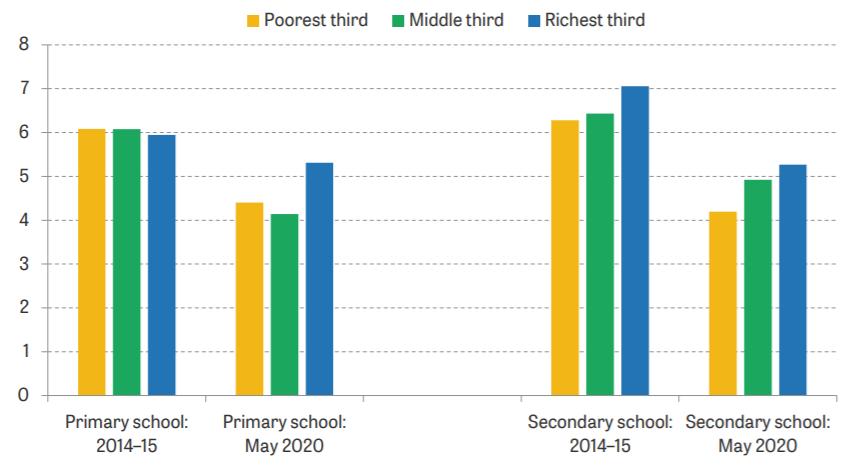

Evidence to date suggests that the Covid-19 crisis is exacerbating educational inequalities. Statistics from early May 2020 show that time spent on educational activities amongst primary school children fell by a quarter, to 4.5 hours a day, from around 6 hours per day before lockdown. However, whereas before lockdown the time spent learning varied little by family income, the Figure below, reproduced from an analysis of time spent on educational activities during a typical weekday, shows that the reduction in time spent learning fell least amongst students from the richest third of families (based on pre-Covid-19 income). Amongst secondary school students there is a clearer gradation by family income in time spent on educational activities prior to the pandemic, with those in the richest third of families spending most time on educational activities. The decrease in time spent on such activities when schools were closed was most pronounced for those from the poorest families.

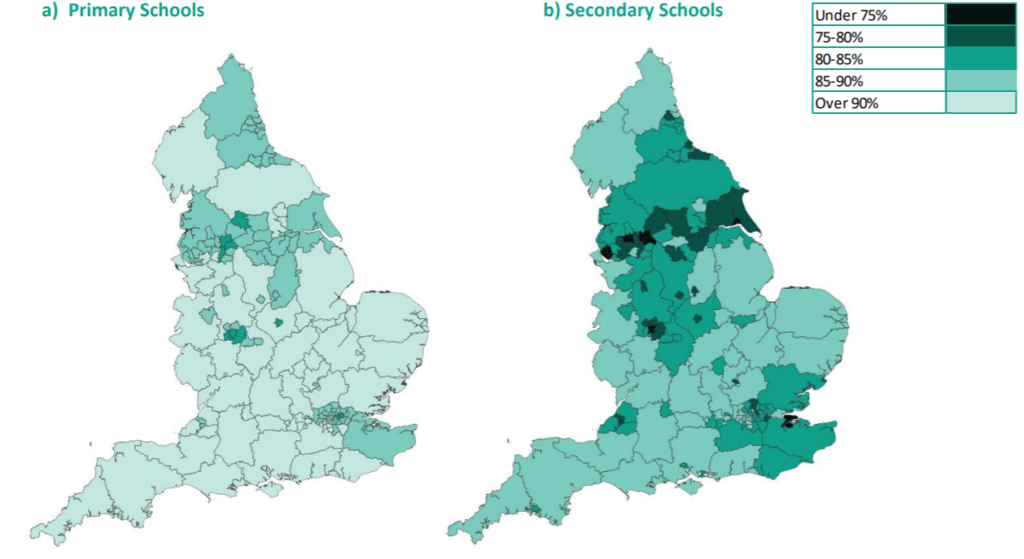

When schools re-opened from June 2020 provision for pupils varied and some pupils in secondary schools were limited to partial attendance. Schools fully re-opened to all pupils in September 2020. Analyses of school attendance and lost schooling across England from September to December 2020 show that pupils in areas with lower GCSE attainment and higher levels of disadvantage have missed more days of school than others; they also had fewer resources at home and from their school to learn effectively. The Figure below shows average attendance rates over the autumn term by local authority – with the West Midlands displaying some of the lower attendance rates (notably in Sandwell and Birmingham).

The Figure shows lower attendance levels in secondary schools than in primary schools and also greater local variation. In Sandwell, the attendance was 72% (one of the lowest rates in England), and in the metropolitan West Midlands, attendance rates were lower than average. However, these figures do not show what could have been significant variations across and within schools by local area; pupils in some year groups could have missed many more days of schooling than others.

The overall picture is one of exacerbated inequalities, with pupils more disadvantaged areas and with lower prior GCSE results losing most days of schooling relative to pre-pandemic levels.

Work

Typically graduates earn more than non-graduates, have better opportunities for training and progression in work and have better working conditions. The Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated labour market inequalities between graduates and non-graduates – and despite progress in raising qualification levels, with a less qualified workforce than nationally, the West Midlands has a larger share of non-graduates.

Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, 71% of employees without a degree either worked in a sector that was locked down or had a job that could not easily be done remotely. For employees with a degree, that figure was just 45%. The fact that more graduates than non-graduates have been able to work from home means that the former have avoided mixing in the workplace. They have also been more likely to preserve their income from work. Compared with proportions prior to the pandemic, there was a 7% reduction in the number of graduates doing any hours of paid work in a given week, compared with a 17% reduction for non-graduates.

Some ethnic groups have suffered disproportionately from disruption to earnings because of their relative concentration in sectors suffering lockdown and/or being amongst the self-employed, who have been at particular risk of losing hours and earnings during the Covid-19 crisis. Pakistani and Bangladeshi men, in particular, have been economically vulnerable in this regard. Bangladeshi men are four times as likely as white British men to have jobs in shut-down industries, due in large part to their concentration in the restaurant sector, and Pakistani men are nearly three times as likely, partly due to their concentration in taxi driving. Pakistani men are over 70% more likely to be self-employed than the white British majority. Research shows that minority groups in hard-hit labour market sectors (and in vulnerable self-employment) are more likely to have other adults and children financially dependent on them. For example, 29% of Bangladeshi working-age men work in a shut-down sector and have a partner who is not in paid work, compared with only 1% of white British men. Hence in these single-earner households, there is more risk of poverty than in a dual-earner household. This means that not only are existing inequalities exacerbated but there is also a risk of them being entrenched for the next generation. This risk is especially pertinent in the West Midlands given its ethnic and demographic composition.

Health

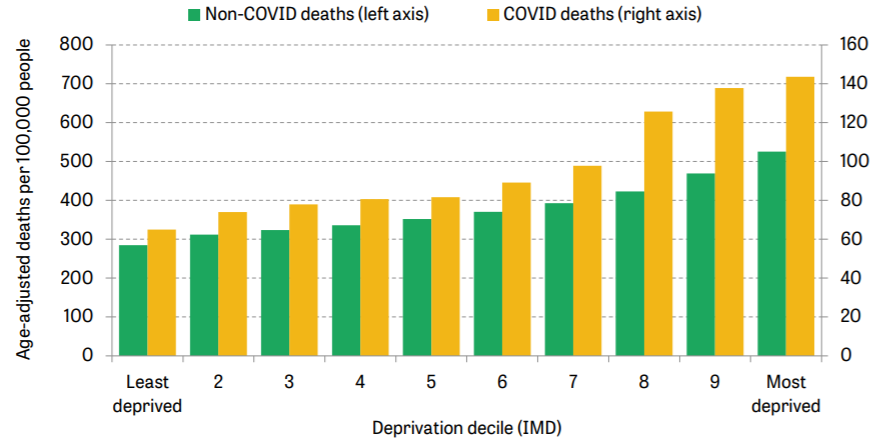

In ‘normal’ times there are disparities in deaths by deprivation. The figure below, showing deaths by local area deprivation for the period March–July 2020, indicates that deaths from Covid-19 are even more socially graded, so exacerbating existing inequalities in deaths by local area deprivation. Mortality rates were twice as high in the most deprived as in the least deprived areas between March and July.

Age-adjusted mortality rates were highest among black African men, at 2.7 times the rate for white men, and among black Caribbean women, at twice the rate of white women. South Asian groups have also been at heightened risk. Overlapping risk factors of geography, deprivation, housing and overcrowding, alongside differences in pre-existing health conditions, explain part of the ethnic group differences in mortality. Moreover, ethnic minorities are over-represented in jobs displaying higher risks of COVID-19 infection and mortality – including care workers, transport workers and security guards.

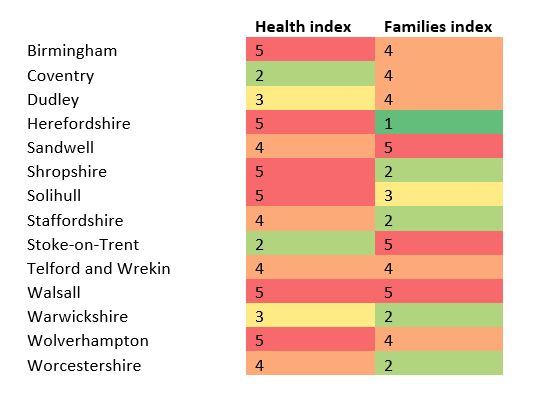

A study on The Geography of the Covid-19 crisis in England presented a ‘Health Index’ showing health-related vulnerability at local authority area level. This measure captures the prevalence of risk factors for experiencing severe symptoms from COVID-19: and the share of people aged 50 or older, and the shares with certain pre-existing health conditions (coronary disease, hypertension and diabetes). The figure below indicates the position of local authorities in the West Midlands by quintile group in England, with a score of ‘5’ indicating that a local area is positioned amongst the 20% most vulnerable in England.

A ‘Families Index’, measuring family vulnerability in the context of Covid-19, is presented above also. This is constructed using local area information on the number of children entitled to free school meals, the rate of referrals to children’s services, and the number of children on child protection plans.

Here several local authorities in the West Midlands emerge as vulnerable on ‘Health’ and ‘Families’ dimensions. Walsall is in the fifth (i.e. most vulnerable) quartile of local areas in England on both the Health Index, while Birmingham, Sandwell and Wolverhampton are in the fifth quartile on one index and the fourth quartile on the other.

Generations

Before the Covid-19 crisis pensioners were becoming relatively better off. Between 2002/3 and 2018/9, the real incomes of the over-60s rose by 28% while the incomes of the under-60s rose by 7%. During 2020 the majority of retired people report no financial impact from the Covid-19 crisis and recession, while a fifth of them report that their financial situation improved. Over the longer-term, this generation has also seen the benefit of defined benefit pension schemes (which are now much less prevalent) and from real house price rises – and it is salient to note here that recent movement in the housing market has been concentrated disproportionately amongst higher value properties.

Conversely, young people have suffered the brunt of job and income loss. Analyses show that by September/October 2020 young people aged 16–25 years were more than twice as likely as older employees to have suffered job loss during the Covid-19. A majority of the group had seen their earnings fall. These disproportionate negative impacts occurred in the context of average earnings among employees currently in their 30s (who were largely in their 20s when the 2008 recession hit) being 7% lower in real terms in 2019 than they had been for their predecessors at the same age in 2008. Hence the Covid-19 crisis exacerbated a longer-standing picture of a difficult labour market for young people.

The generational divide is of particular significance in the West Midlands, given the youthful age structure of its population.

However, within this broad picture of inter-generational inequalities in experience, it is important to remember that there are important intra-generational inequalities too, reflecting the way in which different forms of inequality – by education, employment, health, wealth, location, gender, ethnic group, geography, etc. – intersect.

Looking ahead

As the Covid-19 crisis continues to evolve it is important to monitor and assess whether and how current patterns of inequalities change too and how they might be tackled. The review to date has revealed that largely the Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated existing inequalities but that detailed analysis is needed to show the full picture of variation across sub-groups and geographies. The work of the IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities is continuing yielding new insights in the coming years.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation is also continuing its work on poverty in the UK. In its report on UK Poverty 2020/21 (published on 13th January 2021). An initial assessment suggests that in the early stages of the Covid-19 crisis relative poverty may have fallen, due to two complementary forces. The relative poverty line would have fallen, as average incomes fell due to the labour market effects. At the same time, the income provided for some by the benefits system will have risen, with people benefitting from temporary increases in benefits, albeit counterbalanced by people being pulled into poverty by losing their income from employment. But with much support currently planned to be withdrawn by April 2021, relative poverty is likely to be higher than before the coronavirus outbreak – with increases in poverty likely to be mainly among working-age families affected by the negative labour market change.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.