Dr Darja Reuschke explores how job satisfaction, autonomy, and commute experiences shape employee performance.

Whether working from home impacts employees’ productivity and performance is not a new question, but one that has received renewed attention with media coverage of organisations asking their staff to work fully or a minimum number of days in the office. Most recently, members of Metropolitan Police staff have begun a two-week strike in a dispute over hybrid working.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is one of those employers in the UK that want their staff back in the office due to concerns about low productivity and innovation due to a lack of face-to-face contact. Another concern is likely to be that employees sleep, rest or exercise more when out of sight, based on an ONS report from 2024 that looked at time use patterns of those working from home compared to those working away from home. However, this headline seems misleading. Working hours for employees working from home were similar to those working away from home. The key difference is that home workers gained nearly an extra hour per day by skipping the commute. This suggests that working from home helps employees achieve a better work-life balance.

Measuring employee productivity – especially in the service sector, which dominates the UK economy – is not straightforward. For instance, labour market surveys don’t provide individual productivity data. This complexity contributes to the ongoing debate about working from home, as studies often rely on different methods to compare the performance and productivity of remote workers with those working on-site.

What job satisfaction tells us about working from home and commuting

Job satisfaction is linked to productivity. The two are not the same, but it is assumed that the more satisfied employees are with their jobs, the greater their productivity or performance. I therefore use job satisfaction in my analysis to explore the relationship between working from home and employee productivity.

The data comes from a large, high-quality annual survey of the UK population called Understanding Society and was released in November 2024, with interviews carried out between 2022 and 2024. In this survey, employees were asked how satisfied they were with their jobs on a scale from 1 (completely disappointed) to 7 (completely satisfied). Employees were also asked how much autonomy they have over different aspects of their job including over their work location, whether they have an agreement with their employer to work from home on a regular basis, how often they work from home, and how satisfied they are with their commute.

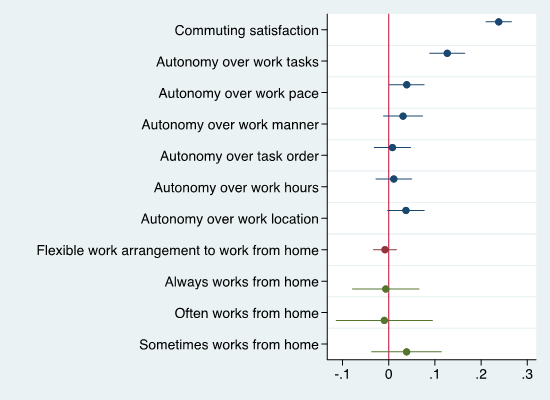

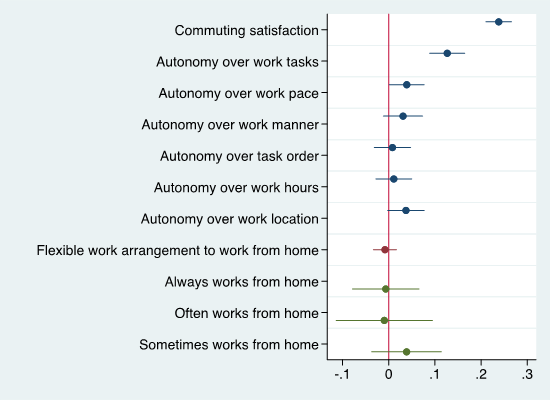

Findings are based on just over 16,000 employees and displayed in Figures 1 and 2 separately for women and men. The estimates are adjusted for age, occupational social group (which captures wage and status) and usual hours worked per week. The vertical red line indicates no relationship with job satisfaction. The closer to the red line, the smaller the relationship, if any. The further away from the line, the greater the relationship.

Looking first at women’s job satisfaction, those who have greater autonomy over their work location and those who work sometimes from home, are more satisfied with their job. Always or often working from home or having an agreement for flexible working from home, are not related to job satisfaction.

Some other aspects of autonomy over the job are important for job satisfaction, in particular, how the work is being done (work manner). However, the strongest relationship with job satisfaction is shown for the satisfaction with the commute. Hence, working from home has some, although limited positive relationship with job satisfaction, but it is the commute that matters the most and more so than other autonomy-enhancing aspects of the job.

Figure 1. Determinants of women’s job satisfaction

Source: Author’s compilation using the Understanding Society wave 14 (2022-2023). Women aged 16-64 who are in paid employment. All coefficients are standardised and adjusted for age, occupational social class and hours worked. The vertical lines indicate the confidence intervals. The colours blue, red and green indicate that the coefficients are from different models.

The better the commute experience, the greater the satisfaction with the job, which will be reflected (in some ways) in work productivity.

For men, working from home or autonomy over work location does not show a relationship with job satisfaction. A number of autonomy-related aspects of the job are not relevant either. What is outstanding again, similar to women, is the strong relationship between job satisfaction and commute satisfaction. The better the commute experience, the greater the satisfaction with the job, which will be reflected (in some ways) in work productivity.

Figure 2. Determinants of men’s job satisfaction

Source: Author’s compilation using the Understanding Society wave 14 (2022-2023). Men aged 16-64 who are in paid employment. All coefficients are standardized and adjusted for age, occupational social class and hours worked. The vertical lines indicate the confidence intervals. The colours blue, red and green indicate that the coefficients are from different models.

Let’s talk about commuting and work productivity

If commute satisfaction is so strongly related to job satisfaction, while working from home is weakly related to women’s job satisfaction and not at all to men’s, then the question of whether working from home is bad for work productivity and the economy, seems the wrong question. We should rather focus on the detrimental impact of commuting on how well employees do on their jobs and on the links between transportation and work productivity. Commute satisfaction is impacted by the accessibility, speed, reliability and quality of transport networks which need to become a more focal point in the discussion about work productivity moving forward.

This blog was written by Dr Darja Reuschke, Associate Professor at City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.