Recently, I had the privilege of travelling to Montreal, to present a paper with my colleague Rebecca Riley and meet with key policy makers. The trip provided a fascinating comparison with the West Midlands, in particular in terms of the success of industrial clusters, approaches to promoting FDI, the use of innovation zones, and university engagement in economic development strategy.

The conference, organised by the Regional Studies Association, focused on the better understand the spatiality, costs and benefits of innovation. This fits closely with research undertaken at City-REDI. Therefore, Rebecca and I presented a joint paper bringing together research which we had worked on separately. Our paper considered how innovation assets, infrastructure, funding, institutions and governance interact at local/regional level. We presented in a session examining public sector innovation, which began with an excellent paper by Thomas Skuzinski from Virginia Tech University on the changing nature of local autonomy in US regions and how this offers opportunities for innovation.

My part of our paper analysed data from the report I published earlier this year examining the value of central government and research funding secured by institutions in different Local Enterprise Partnership[1] areas. I explained that my analysis of funding awards and interviews I conducted with senior decision makers in LEPs across England found that places that have more capacity win more funding. Capacity issues particularly affect rural and smaller LEPs. Staffing levels, networking capacity and a history of partnerships were suggested to be factors in why some areas have received higher grant awards than others. I emphasised how having one or more research-intensive universities is central to which areas received the highest value of Horizon 2020 and UK Research and Innovation funding. I stressed the crucial role that universities can play in relation to local economic development as ‘change agents’.

Rebecca then presented her research examining how people in ‘grey’ space roles (that bridge academia and policy making) within universities drive forward the role of universities in local economic development. Rebecca has triangulated her analysis through a database of observations of individuals in grey space roles and a pilot of in-depth questionnaires focussing on individual’s roles, their development and their objectives. She emphasised the importance of universities having employees with experiences in the ‘grey space’ in order to create the right innovation ecosystem. Rebecca pointed out challenges which people in these roles face including:

- tension between academic and non-academic research;

- tension over the need to publish for it to ‘count’;

- difficulties regarding how to measure impact in policy development and economic development where impacts are long term and not immediate;

- uncertainty regarding how to integrate these roles in funding applications across universities;

- lack of a corporate approach to setting the objectives and vision for the roles.

Following our paper, Peter O’Brien from Yorkshire Universities examined challenges promoting innovation in the current UK Higher Education environment, arguing that limited capacity and autonomy of sub-national institutions hampers regional innovation governance and institutional frameworks. Conrad Parke from the University Birmingham explored bottom-up innovation in a project aiming to unlock the skills and talents of migrants and refugees. The papers tied together really well and there was keen interest in how City-REDI is developing a hybrid academic/public policy/consultancy model where staff have a mix of skills, functions and competencies including in the grey space. We explained how City-REDI research and analysis is enshrined in developing a strategy for the UK West Midlands Region.

During the conference we met with the following organisations:

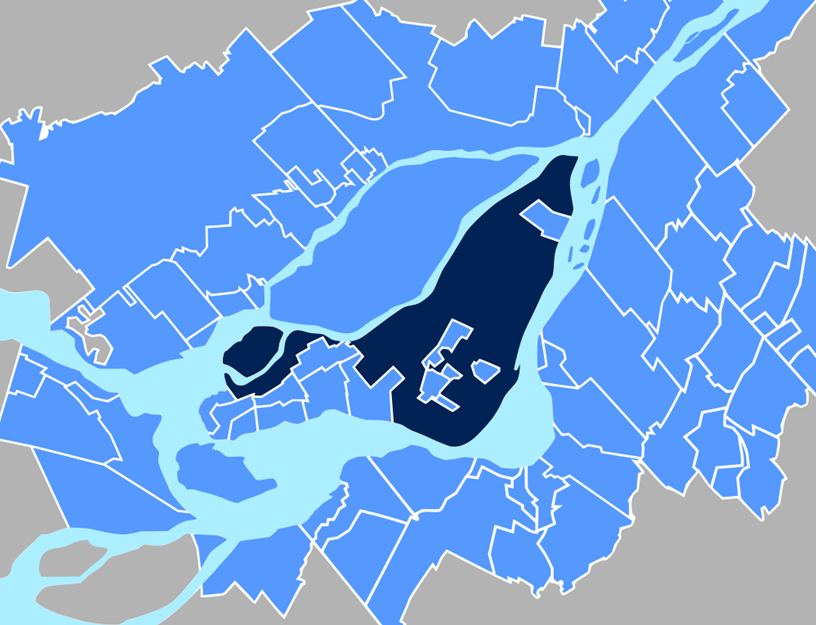

- The Montreal Metropolitan Community, a supramunicipal level of government for the Greater Montreal Area, responsible for the planning, coordination and finance of an area incorporating 82 municipalities and a population of 4 million. Its responsibilities include urban planning, economic development, waste management and public transportation.

- Montréal International, Greater Montreal’s economic promotion agency. Established over 20 years ago, its mandate is to attract direct foreign investment, international organisations, entrepreneurs, talented workers and international students to the region.

- The Quartier de l’Innovation (QI), an experimental innovation zone in the heart of Montreal which brings together academics, entrepreneurs and residents to generate benefits for society. The QI is supported by the Government of Canada, the Government of Quebec, the City of Montreal, four universities, and nearly thirty private partners. The zone aims to develop local solutions to global innovation challenges.

Montreal city has a population of just over 2 million. Greater Montreal has more than 4 million residents. The population of Birmingham is nearly 1.2 million, whilst the West Midlands Combined Authority area has a resident population of over 2.9 million.

We identified parallels and contrasts between Greater Montreal and the West Midlands. Both areas have similar constitutional structures and have recently experienced an economic renaissance. In the West Midlands, GVA is growing at the same rate as the UK national average and GVA per hour is increasing at a rate significantly above the national average. Greater Montreal experienced considerable job growth between 2001 and 2014 with the number of jobs rising by about 300,000 to 2.02 million. The economic base in both areas has deindustrialised over the last twenty years as the number of jobs in the knowledge and service sectors has increased. Professional services in particular have grown. Montreal was ranked the 24th largest financial centre in 2018 whilst the West Midlands is home to more than 43,000 business, professional and financial services companies who employ 321,000 people making it the most significant business hub outside of London. Both areas face common challenges including historically low skills levels.

Key differences between Greater Montreal and the West Midlands that we observed are:

- Over the last 15 years, Montreal has established 11 clusters of excellence in sectors from aerospace, to finance, to life sciences. Whilst the West Midlands identifies clusters in sectors such as the automotive industry in its Local Industrial Strategy, the clusters are less established than in Montreal. One explanation we heard for the success of the clusters was how they are led by the private sector and a highly collaborative environment exists in Canada. The clusters are designed to operate according to a model where when the private sector face issues, they ask academics for support and then apply to the government for funding to implement initiatives to address the issues. The ability of all industries to speak as a single voice was suggested to be particularly important in the growth of businesses in the area, for example collective pressure had led the Québec government to reverse plans to cut tax credits by 20%. It was also said to be important in identifying skills shortages in the clusters and implementing training policies to address them.

- Montreal/Quebec appears to have adopted a more structured approach to attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) than the West Midlands. A clear division looks to exist in Montreal between the government which offers funding to businesses moving to the area and Montréal International which promotes the area and helps businesses with their business plans. Montréal International is funded by 3 levels of government (80%) and the private sector (20%), which they argue offers them more flexibility. They have an international mobility department which helps companies to obtain work visas for international staff. The approach appears to be working well with Montreal ranked 17th globally in terms of FDI value attracted to cities, and being home to 65 international organisations.

- The use of innovation zones in Montreal. Crucial success factors highlighted in our meetings were: the use of international benchmarking to identify innovation ideas, mix of public (40%) and private (60%) funding, not being afraid to fail, seeking to constantly reinvent the zones in response to innovation trends, humanising and involving local people in new technology from the beginning rather than imposing it on them, animation, meetings with senior representatives from all universities in the city.

- Despite the focus during the conference on the links between Higher Education Institutions and Economic Development it appears that universities in Greater Montreal are less involved in supporting local economic strategy development than universities in the West Midlands. We heard about a lack of collaboration between universities caused by competition between universities for students. There was lots of interest among the policy makers in the civic university model in the West Midlands to deepen analysis and develop longer-term policy solutions.

The obvious economic parallels between the West Midlands and Greater Montreal offered valuable academic and policy insights. While links between the Higher Education sector and economic development in the West Midlands are already strong, Greater Montreal offers a valuable case-study into possible future economic strategy to develop innovation zones and attract greater levels of FDI.

[1] business-led partnerships linking the private sector, local authorities, higher and further education and the voluntary sector.

This blog was written by Dr Abigail Taylor, Research Fellow, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham