Sara Hassan summarises the key takeaways from literature on public transport and healthcare services accessibility with a special focus on disadvantaged and deprived areas.

Public transport (PT) is very important in terms of providing independence for groups of people who cannot drive, cycle or walk; it provides them with the chance to access services such as employment and healthcare independently, as well as preventing them from being excluded from society through engaging with people and being around them routinely. While some studies have highlighted potential negative impacts from public transport such as the opportunity to pass on viral infections, the larger challenges regarding public transport have been found to be in the lack of availability and accessibility. Still, many low-income households can perceive public transport to be costly. This is further exacerbated when public transport networks are disconnected which raises the cost and presents a barrier to accessibility.

There is international evidence to suggest that transport barriers are a contributory cause of missed and cancelled health appointments, delays in care, and non-compliance with prescribed medication. These forms of disrupted and impaired care are associated with adverse health outcomes. The economic costs (time and money) of accessing health care are borne by those with the highest attendance at health services due to the nature of their conditions and travelling the furthest distances. There is evidence that making these journeys, and parking, in particular, incurs some stress and anxiety. Finally, there are further costs to health services due to missed appointments.

This blog discusses the impact of public transport availability and accessibility on public health particularly for people who suffer from some physical conditions or disabilities. Many of the studies also note that mobility and accessibility inequalities are highly correlated with social disadvantage. This means that some social groups are more at risk from mobility and accessibility inequalities than others. This can largely limit not only their ability to travel inexpensively but impact their social engagement and employment opportunities. This long read explains how better transport availability and accessibility can be a route to better health Other more recent challenges for public transport and health include the negative branding of PT during the pandemic which affected travel patterns during the pandemic.

In Birmingham, public transport is particularly important as approximately 38 per cent of households in the area do not have access to a car (information collected from Census 2001). The highest numbers of households with no access to a car are concentrated around the Birmingham Treatment Centre, Newtown, Tipton, Great Bridge and West Bromwich health centres. A report from Centre for Cities in 2020 mentions Birmingham among other major English cities as being in particularly significant need of new public transport infrastructure to stop congestion and capacity constraints. Birmingham is also specifically noted for its “slow” and inaccessible public transport.

Health impact of Transport

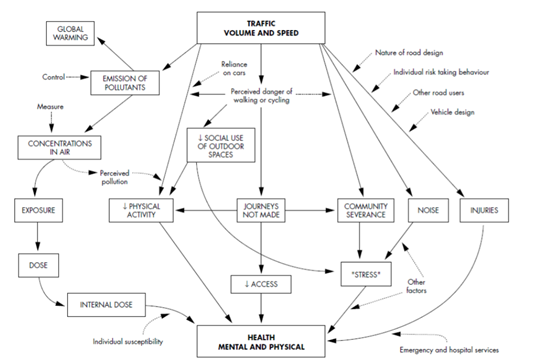

Transport is a complex system affected by infrastructure, individual characteristics and behaviours and can have a broad impact on health. Joffe and Mindell (2002) developed a map (Figure 1) showing the transport components that could be linked to health outcomes. (These include issues such as air and noise pollution, road design, impact on physical activity, road injuries and access, illustrating the diverse nature of the policy areas that are related to transport and may have a direct or indirect impact on health.

Low-income households, accessibility and public policy

An evidence review by the Government Office for Science in 2019, shows that many people in the UK may not be able to access important local services and activities, such as jobs, learning, healthcare, food shopping or leisure as a result of a lack of adequate transport provision. Problems with transport and poor links to opportunity destinations can also contribute to social isolation, by preventing full participation in these life-enhancing opportunities. The review identified that the published academic and policy evidence for this specific topic is quite sparse. This means that some social groups are more at risk from mobility and accessibility inequalities than others, namely:

- Lowest income households, 40% still have no car access – female heads of household, children, young and older people, black and minority ethnic (BME) and disabled people are concentrated in this quintile.

- children, the elderly, people with mental disabilities or long-term illnesses, are also more exposed to health-related externalities of the transport system:

- People living in disadvantaged areas tend to live in more hazardous environments, with greater proximity to high volumes of fast-moving traffic and levels of on-street parking and, as such, they have higher levels of exposure to road traffic risk.

- Young people (11–15 years) from disadvantaged areas are more involved in traffic injuries than their counterparts living in other urban areas. The risk is highest on main roads and on residential roads near shops and leisure services.

The review states that the lack of private vehicles in low-income households, combined with limited public transport services in many peripheral social housing estates, considerably exacerbates the problem in many parts of the UK. There is an urgent need for policies to more explicitly recognise the important social value of transport. Public transport service limitations, combined with largely unregulated land-use development, are driving a mobility culture that most advantages already highly mobile and well-off sections of the population while worsening the mobility and accessibility opportunities of the most socially disadvantaged in the UK.

Transport users often highlight the complexity of planning journeys, the length of time and the expense of making journeys. A report by Cambridgeshire JSNA demonstrates how getting to hospitals is particularly difficult for people without a car or who are living in places with inadequate public transport options. This lack of access can lead to missed health appointments and associated delays in medical interventions. An estimated 10% of hospital outpatient appointments are missed due to transport problems, thereby putting people’s health and wellbeing at risk and causing unnecessary costs to taxpayers.

Recommendations and further research

Strong and coherent networks of public transport and active travel are amongst the solutions that need to be widely investigated to tackle the issues and challenges of inequalities in access to healthcare. A report by the Department for transport states that there is a potential for change with data and connectivity transforming journeys, emerging modes of transport, rising travel demand, and new digitally enabled business models (e.g. journey sharing). While new technology and business models could deliver benefits for society, the environment and the economy, there are potential risks from failing to manage emerging technologies and services effectively, including safety and security threats, effects on health and wellbeing, loss of jobs and privacy issues. This needs to be considered alongside the future of healthcare accessibility.

There is a need to re-articulate the challenges and barriers of public transport and other modes to access healthcare, particularly in areas of socio-economic disadvantage. Many novel methodologies can help identify these challenges. There is a need to include much wider participatory approaches to planning transport, particularly in relation to healthcare accessibility. These approaches can reveal many travel-behaviour patterns and a deeper understanding of the barriers and challenges. However, these approaches can also help in shaping policies that are targeted and more inclusive. These co-created solutions have more public acceptability than top-down solutions most common in transport planning. This can be very beneficial to the enhancement of health and wellbeing in Birmingham and the West Midlands.

This blog was written by Sara Hassan, Research Fellow, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

Appreciate this post. Will try it out.