In this blog, Professor Anne Green discusses a report published by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Housing and Social Mobility called “Improving Opportunities: How to support social housing tenants into sustainable employment”, which was released in October. The report outlines the role that social housing providers can play in supporting households and communities into sustainable livelihoods through employment both to support their well-being and to contribute to the broader levelling up agenda. This reflects the role of social housing providers play as local anchor institutions – as employers, builders, deliverers of employment support programmes, partners and placemakers in local areas.

A function for social housing in stimulating the economy

A recent briefing from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation highlighted a role for social housing in stimulating the economy. It highlights four main reasons why investing in housing (with a greater prioritisation of homes for social rent) has fiscal advantages, including over and above investing in market-based tenures. First, in the short-term, investment in housing can reduce the housing benefit bill and universal credit expenditure for those in the construction sector. Secondly, investment in housing creates jobs, both directly in the construction sector and indirectly through the supply chain. This is exemplified through both new build housing and schemes to retrofit the existing stock. Thirdly, the lag between investment and impact is often far shorter in housing than in other types of investments. Fourthly, housing investment can create significant tax revenues.

The role of social housing

Social housing has a key role to play in addressing challenges of housing affordability. This has been identified as a key issue in the West Midlands with the WMCA introducing a localised definition of affordable housing earlier in 2020, based on local people paying no more than of their salary on rent or mortgages. Two of the defining characteristics of the sector are (1) tenure security, and (2) sub-market rents.

In recent decades the stock of social rented housing in England has decreased. Initially, this occurred via the ‘Right to Buy’ programme and then through building failing to keep up with demand. In recent years the proportion of people living in the private rented sector has increased. Traditionally, private renting played an important role in providing accommodation for young people and for those wanting a short-term solution to housing need, but increasingly families with children and older people are housed in the private rented sector for longer durations. Yet private renters face the highest housing costs of any tenure.

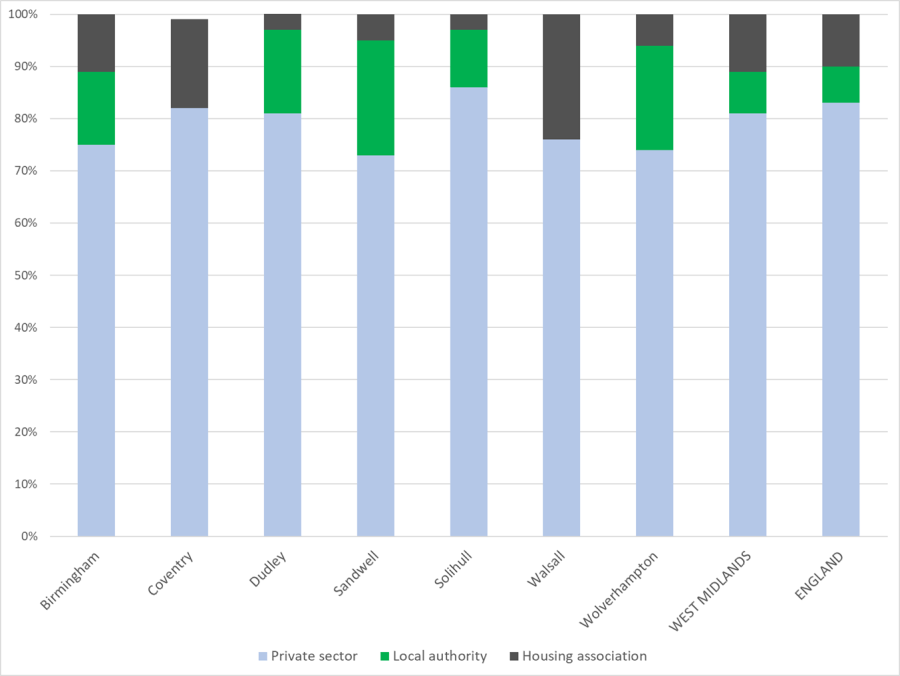

Housing stock data by local authority for 2019 published by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) shows that in all parts of the West Midlands Metropolitan area except Solihull the social rented sector (with a distinction made in the chart below between social rented housing provided by local authorities and housing associations) accounts for a larger share of total housing than in England (13%). The diagram below shows that the share of social rented housing is highest in Sandwell (27%), Wolverhampton (26%), Birmingham (25%) and Walsall (24%).

Tenure, work and poverty

Research studies have shown poorer labour market outcomes associated with living in social rented housing. Analyses for the period from 2014 to 2018 showed that just over half of working-age social tenants were at work compared to 80% of those owning or in the market rented sector. The rate of economic inactivity was twice as high in the social rented sectors as in other tenures combined.

These poorer labour market outcomes are explained largely, but not entirely, the characteristics of working-age social housing tenants in social housing that are associated with low levels of labour market participation. These include lower-level qualifications (which weaken individuals’ position in the labour market), long-term illness and disability and having dependent children – lone parents are disproportionately social housing tenants.

These characteristics are reflective of the way that social rented housing is allocated to those people with priority housing needs. Contextual factors, such as the concentration of social rented housing in weaker labour market areas, also help to explain part of the poorer labour market outcomes for tenants in the social rented sector.

A more recent report by the Resolution Foundation in April 2020 highlighted how for many tenants in the social rented sector entering work reduces poverty, but that in-work poverty remains a key issue. Low pay and short hours increase the risk of poverty. Moreover, when in work interacting with the benefits system can be problematic, which in turn leads to some tenants being risk-averse in entering employment when sustainability is uncertain.

Barriers to employment for tenants in the social rented sector highlighted by the APPG report on Housing and Social Mobility include:

– Personal characteristics: lack of/ low educational qualifications, lack of/ poor digital skills (which are increasingly important in the Covid-19 crisis), poorer mental and physical health, low aspirations;

– Contextual factors: notably cost and reliability of public transport (especially on peripheral estates) and cost and availability of childcare.

Housing associations as anchor institutions

Housing associations play a social purpose and are embedded in and committed to the communities they house and the local places where they operate. They can improve local economic and social wellbeing in the way they spend, employ and use their land and assets. Their economic footprint extends beyond the people they employ and has an impact beyond their residents.

They are in a strong position to act to link social housing tenants to employment because of the long-term (and perceived trusted) relationship with tenants. Many social housing providers have shown their commitment to employment support by building up advice teams providing intensive but flexible and bespoke one-to-one support, including post-placement monitoring. Many occupy a leading and/or strategic partner role in local labour market employment support and training collaborations. They have supply chains and procurement purchasing power which they can and do use to support tenants and residents in the labour market, alongside their role as direct employers.

Currently the Birmingham Anchor Network – which includes two universities, University Hospitals Birmingham, the West Midland Police and Crime Commissioner and housing providers – is working to link social housing residents to employment. The Pioneer Group’s team of employment advisors is working to link residents to job opportunities in hospitals and the police force (which are recruiting during the Covid-19 crisis), while at the same time enabling these large employers to learn how to engage disadvantaged neighbourhoods in their recruitment campaigns.

Recommendations from the APPG Inquiry into Housing and Employment

On the basis of previous research and new evidence, the Inquiry’s recommendations included:

- More regional and national public funding resources should invest in neighbourhoods to reinforce positive social networks helping social landlords be better placed to work with statutory bodies and deliver employment and training programmes locally

- Greater use of tailored joined up one-to-one support which focuses not only on employment opportunities but also finding out what the individual wants and how to actually help them train and get them into a job and to give them confidence in their jobs

- Devolution of employment support programmes to more functional labour market areas and encouragement of providers to form consortia at this scale to deliver key local programmes

- Encourage and support greater partnership working between housing associations and other organisations – e.g. further education colleges, employers and other organisations that could then help provide access to the job market

- Provision of time-limited financial support on entering the labour market to cover costs associated with the transition to employment – in recognition that keeping a job is hard

- Promotion of better labour market outcomes for local people via procurement and supply chain routes through local labour clauses, apprenticeships and other matching of people to opportunities

- Greater clarity and certainty about future funding (such as the Shared Prosperity Fund)

- Support across the whole employment journey – from pre-employment to job entry, to sustaining employment, to progression in work

In the context of the Covid-19 crisis, social rented housing providers have a key role to play in helping some of their residents who have been hard hit by job loss link to new employment opportunities.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.