In this blog, Dr Charlotte Hoole provides a summary of the paper she presented at the RSA annual conference in Lugano, Switzerland. Her co-authors include Dr Peter Lee (University of Birmingham), Dr Eric Chu (University of Birmingham), Dr Oliver Dlabac (University of Zurich), Roman Zwicky (University of Zurich).

In this blog, Dr Charlotte Hoole provides a summary of the paper she presented at the RSA annual conference in Lugano, Switzerland. Her co-authors include Dr Peter Lee (University of Birmingham), Dr Eric Chu (University of Birmingham), Dr Oliver Dlabac (University of Zurich), Roman Zwicky (University of Zurich).

The democratic foundations of the Just City: Urban planning politics in three European cities

This project investigates the roles of leadership, stakeholder cooperation and democratic scrutiny in different institutional and regulatory settings for pursuing urban planning policies that arguably contribute more or less to the ideal of the Just City.

The study aims to better understand whether cities are merely dependent on structural forces (such as the national institutional and regulatory environment) or whether it is in the power of urban political leaders to enforce urban planning policies that are in line with the ideal of the Just City. This is captured by the following two research questions:

RQ1: How do urban planning systems impact on Just City outcomes?

RQ2: What is the role of urban political leaders in contributing to the Just City?

We are using Susan Fainstein’s framework to assess social justice according to the three criteria of ‘ghettoization’, ‘gentrification’ and ‘affordability’. According to this framework, local policy should work towards:

- Avoiding involuntary spatial concentrations of population groups (e.g. non-white groups, low-income groups) (ghettoization)

- Counteracting displacement originating from the transformation of working-class or vacant areas of a city into middle-class residential and/or commercial use areas (gentrification)

- Creating and preserving affordable and decent housing that is accessible to economically and socially deprived groups (affordability)

This framework is being used to assess the link between urban planning policies and the way that social injustice becomes visible in space to inform policies aimed at tackling it.

The research is being carried out in three European cities – Birmingham, Zurich and Lyon. These cities have been chosen as those which are different but typical in terms of their institutional settings. Birmingham has a centralist governance system and Council-leader local government form, Lyon has a regionalist governance system and mayoral local government form, and Zurich has a localist governance system and collective local government form. Together, they provide three distinct urban planning contexts for investigation and for comparisons to be drawn.

Our methodology follows a two-step approach. To begin, we have mapped data in line with the three criteria in each city over time. We’ve used mainly census data for reasons of comparability across the three cities. This will go alongside an examination of national and local policy documents for each city in line with RQ1. The second phase is to carry out up to 20 semi-structured interviews in each city with local politicians and planning officials to explore RQ2. Now I will introduce you to the Birmingham case study and to some of our early analysis.

Birmingham Case Study

Following de-industrialisation and the loss of manufacturing employment in the 1970s, concerted efforts have been made to restructure Birmingham’s economic foundations and social composition. Initially, efforts were focused on regenerating older urban areas, improving housing conditions, and enhancing the existing built-up area. However, by the late 1980s, the focus was firmly on reinventing Birmingham and changing its national and international image, with the city centre as a focal point for action. Since this time, the emphasis has been placed on private sector initiatives and ‘flagship schemes’. This is not particularly unique to Birmingham but follows the kind of ‘urban renaissance’ that many post-industrial cities set out to achieve in the 1980s and 1990s.

Above are some examples of the kind of urban development that Birmingham has seen in the last two decades. It’s hard to deny that these haven’t been really positive for Birmingham, they have. However, getting beyond the kind of headline, easily visible successes that the city has achieved, for this project we are more interested in what has been going on around this in terms of socio-spatial outcomes over this same period across the whole city – according to ghettoization, gentrification and affordability. It is the first of these dimensions that I will introduce you to below.

Ghettoization

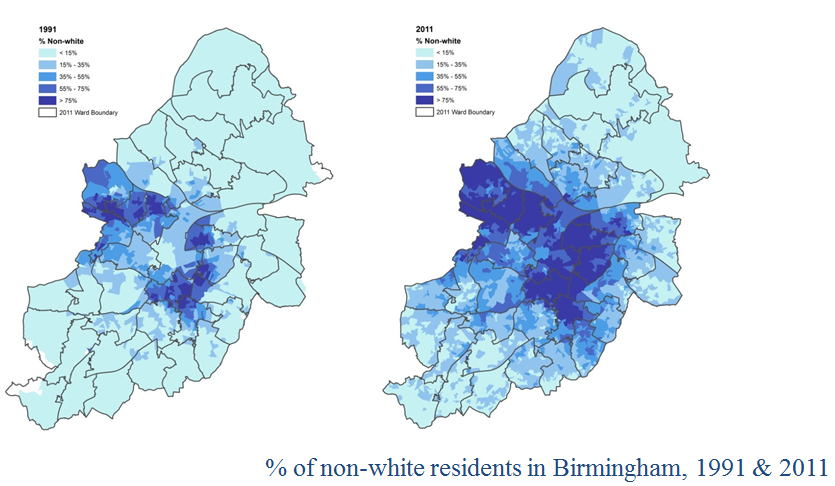

These maps show the spatial distribution of non-white residents in Birmingham for 1991 and 2011, with high concentrations found in the inner-city for both. However, the spatial distribution of this group has become more concentrated and has experienced spread over this time, with non-white residents in the dark blue areas now making up over 75% of the population in those areas. There are several reasons that may have contributed to the pattern we see here.

Firstly, Birmingham’s non-white population grew substantially over this period, from 17.5% of Birmingham’s total population in 1991 to 42.1% in 2011 (ONS). Possible reasons for this increase include a continuation of non-white migration (including chain-migration) and the natural growth of non-white communities. But why the inner-city?

According to literature and an initial scoping of local policy documents, other reasons include:

- The initial settlement of post-war migrants influenced by the available stock of vacant and affordable dwellings. This was also influenced by a high proportion being employed in factories in the inner-city.

- A lack of opportunity for non-white residents to access housing in other areas of the city due to issues of affordability.

- An outflow of white mobile residents from the inner city.

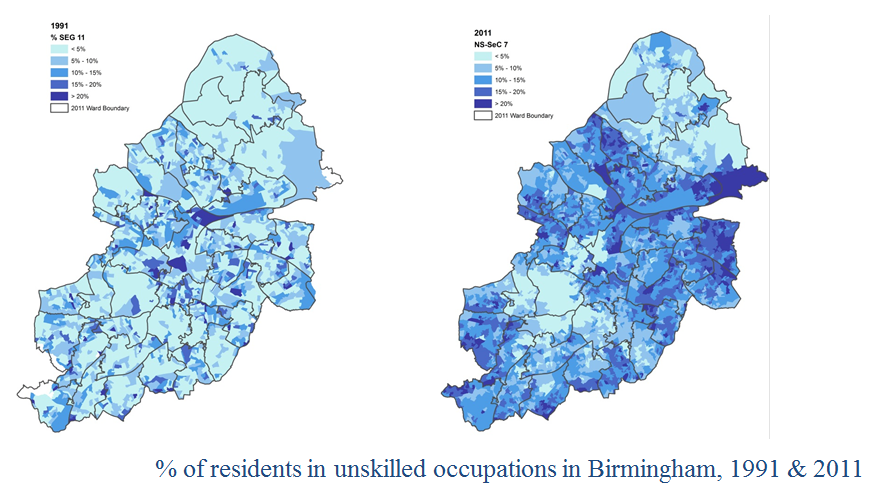

Another group we have looked at for assessing ‘ghettoization’ in Birmingham are those in ‘unskilled/routine’ occupations, with the maps below showing data for 1991 and 2011.

In comparison to 1991, in 2011 we find higher concentrations and a clearer contrast between areas with high and low proportions of residents in unskilled/routine occupation. Generally, the distribution we see is similar to Birmingham’s non-white population, except in areas on the edge of the city to the east and south – these are predominantly white areas. These areas also align closely with out-of-city social housing estates.

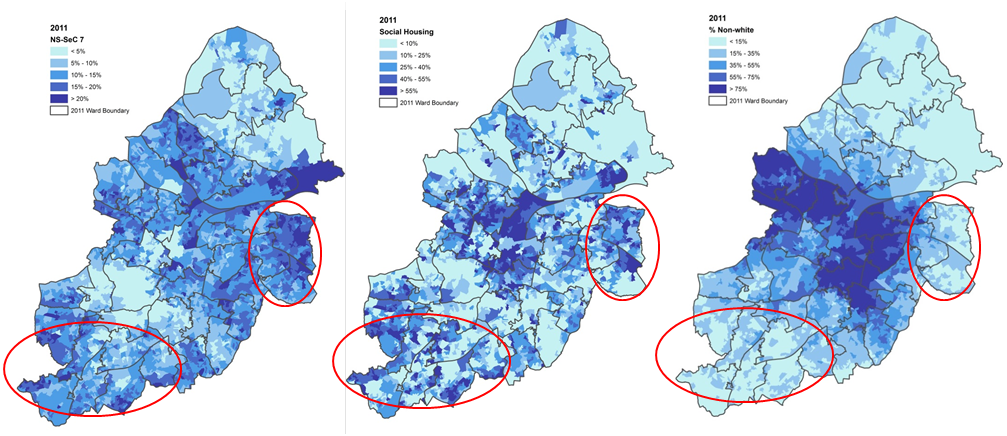

The maps above highlight areas of the city (circled in red) that have high proportions of residents in unskilled occupations (left), high proportions of residents in social rented housing (middle), and high proportions of residents that are white (right). This leads us to our second narrative of ghettoization in Birmingham – out-of-city social housing estates.

Between the 1920s and 1970s, many residents living in inner-city slums took the opportunity to move to newly developed social housing estates on the outskirts of the city. Research has shown that these were preferentially allocated to white, working-class residents. However, following the onset of deindustrialisation in the late 1970s, traditional working-class communities collapsed and social housing increasingly became a means to accommodate the most vulnerable in society. These were residents who were unable to exercise their right to buy under the UK’s Right to Buy scheme in the 1980s or were otherwise unable to purchase private housing on the open market. In the years since social housing estates have faced acute problems such as high levels of deprivation and unemployment. The latter is particularly significant for those that are peripherally located and struggle to access jobs in the city centre.

Taken at face value, early evidence suggests that urban regeneration in Birmingham has largely not been concerned by issues of spatial justice over recent decades. This can be seen, for example, in the way that investment in the city centre that caters for a growing professional population has been prioritised over tackling deprivation and unemployment in areas in the inner-city and peripheral social housing estates. This can also be found in the literature, with Barber and Hall (2008) referring to the “partial nature of the city’s overall economy”, and Henry and Passmore (1999) claiming that “flagship projects have created an elite international enclave within Birmingham city centre… which is increasingly divorced from its regional/local context”.

The next step for this project, however, is to investigate to what extent local leaders have been in control of the city’s development since the early 1980s in a national policy context that is highly centralised?

This blog was written by Dr Charlotte Hoole, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

Wards with low income levels and high levels of deprivation in the inner city, and in the ex-council estate fringes differ in more than access to employment opportunities in the city centre, or ethnic composition. Walk around, say, Small Heath, and then walk through the estates of Kings Norton, and the difference is clear. The inner ward has a local centre, and a High Street full of small businesses, including the services that are required for a local economy (accountants, lawyers). I saw figures some time ago showing public library usage by ward, and that, too showed that library use was lowest in places like Kings Norton, and highest in places like Ladywood. My conclusion is that inner city ‘poor’ wards have the capacity to generate their own wealth and employment opportunities, whereas the outer fringes don’t. Just an observation from a flaneur!