Dr Deniz Sevinc looks at the disproportionately strong effects of Covid-19 on minority ethnic groups within the West Midlands Region and the struggles they face at work, at home, and in the healthcare system.

Covid-19 has exacerbated longstanding inequalities affecting Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups in the UK as mounting evidence suggests that BAME communities were disproportionally hit hardest by the pandemic. According to recent research by two leading think tanks – IPPR and the Runnymede Trust – almost 60,000 more coronavirus deaths could have occurred in England and Wales if White people faced the same risk as BAME communities. Stripping out the effects of age and sex it is estimated that at least 2,500 Black and South Asian deaths could have been avoided (IPPR, 2020).

Now that we are in the middle of the second wave we are beginning to see the recurrence of what happened the first time around in the West Midlands and also across the UK. The figure below shows that a disproportionately large number of people from ethnic minorities are ending up in intensive care.

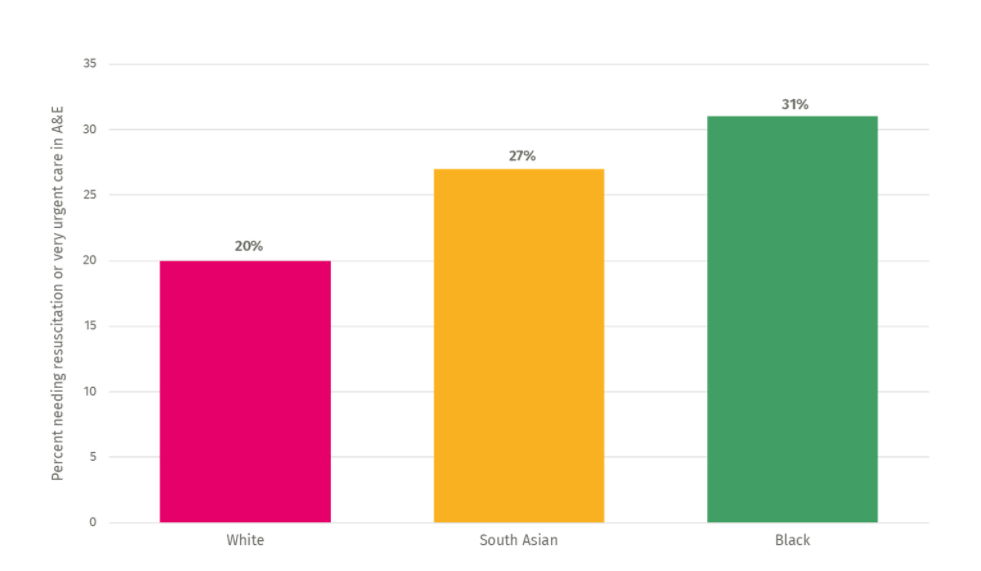

It is worth noting that non-White patients are often sicker when they arrive at A&E. In the UK, 55 per cent of black patients and 35 per cent of South Asian patients are more likely to need resuscitation or very urgent care than white patients according to IPPR’s research.

Public Health England confirms that people from Black ethnic groups were most likely to be diagnosed with Covid-19 in the hospital testing data and death rates from Covid-19 after their arrival at A&E were highest among people of Black and Asian ethnic groups in the West Midlands (Public Health England, 2020a). In addition, they show that Bangladeshi households had around twice the risk of death than people of White British households across the region, whereas Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Other Asian, Caribbean and Other Black ethnicity households had between 10 and 50 per cent higher risk of death when compared to White British (Public Health England, 2020a). As shown in the figure below black and south Asian patients with Covid-19 are more likely to need resuscitation or very urgent care than white patients with Covid-19.

Structural differences or social factors?

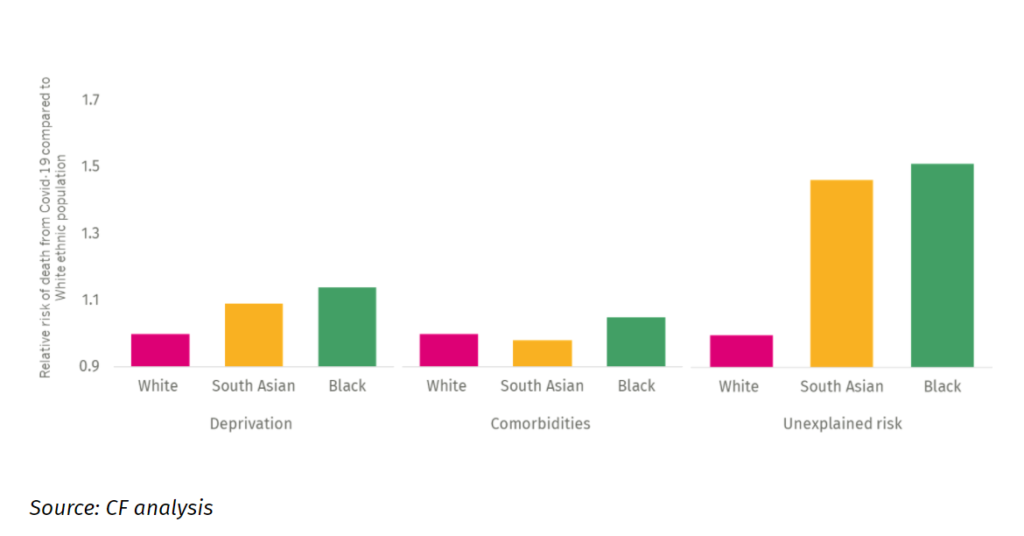

It is well documented that BAME groups face structural barriers and IPPR’s research finds that underlying diseases and genetic factors explain only a fraction of what is a ‘massive risk disparity’ (IPPR, 2020).

They suggest that although genetic factors play a significant part in explaining ethnic inequalities, structural differences are the main drivers of these inequalities such as differences in jobs they do, the area they live or the conditions they live in. Thus, in the rest of this narrative, we explore these contributing social factors for the BAME community in the West Midlands region.

Why ethnic inequalities in Covid-19 are playing out again in the West Midlands?

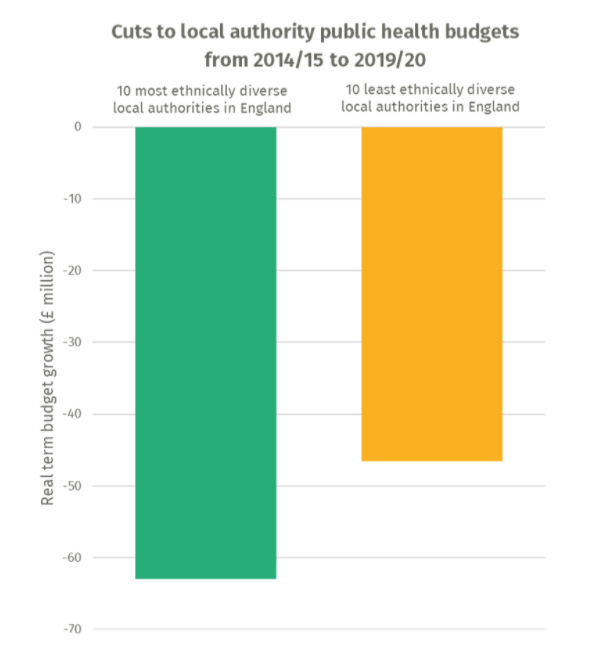

Cuts to local authority public health budgets and lack of sustainable NHS funding in ethnically diverse areas

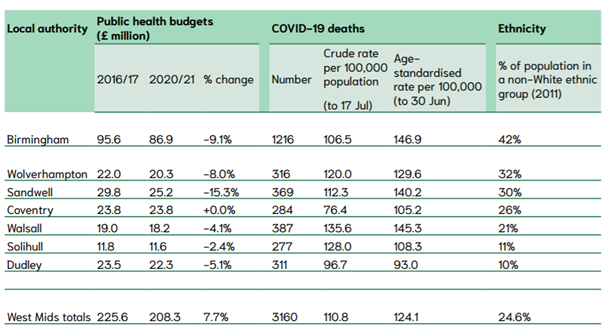

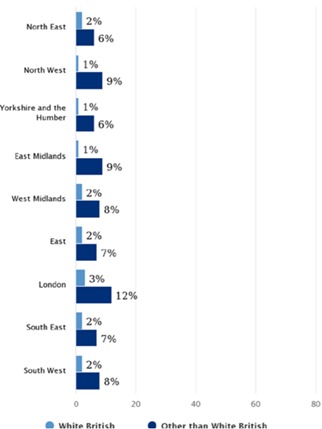

An important concern here is the lack of NHS funding and how it should be allocated across regions so that those people at greatest risk get the greatest measure of intervention. Recent IPPR findings as shown in the Figure below suggest that minority ethnic communities have been exposed to significant public health budget cuts in recent years. Particularly, the ten most ethnically diverse local authorities in the UK have lost £15 million more in public health budget compared to the ten least ethnically diverse local authorities due to cuts to local authority public health cuts (IPPR, 2020).

Public health funding by most diverse areas, the West Midlands region. Source: House of Commons LibraryThese cuts are particularly pronounced for the West Midlands region, statistics reveal that Sandwell, Wolverhampton and Birmingham – the most ethnically diverse local authority areas in the region – have suffered significant cuts to public health budgets over the last five years, of 15 per cent, 8 per cent and 9 per cent respectively as shown in the figure above (NHS BAME Network Taskforce, 2020). It is noteworthy to mention that these figures are well above the national average cuts to public health budgets of 5 per cent.

Ethnic inequalities in housing

Risks associated with Covid-19 mortality are significantly exacerbated by overcrowded housing, mainly a common challenge faced by BAME groups across the country. IPPR’s research suggests that 24 per cent of Bangladeshi households and 15 per cent of Black African households are classified as overcrowded compared to only 2 per cent of White households in the UK (IPPR, 2020).

Overcrowded housing and income inequality are independently associated with COVID-19 mortality as households cannot often afford to move to a larger house and self-isolation rules are much more difficult to implement in overcrowded households. The West Midlands region has an aggregated 1.72 homeless households per 100,000 households that are relatively higher than the national average of 1.49. As far as temporary accommodation is concerned, 1.91 per 100,000 households live in temporary accommodation in the West Midlands region (WMCA, 2020). Birmingham has the highest rate of 6.7 per 100,000 households and 81.7 per cent of these households are with children, followed by Coventry (4.01 per 100,000 households and 56.9 per cent with children) (WMCA, 2020).

As far as housing conditions are concerned, in the West Midlands region overcrowding is four times higher in the ethnic minority community than the white British community and 2.8 per cent live in overcrowded houses (which is similar to the national figure 3 per cent) (NHS BAME Network, 2020).

Ethnic inequalities in the workforce

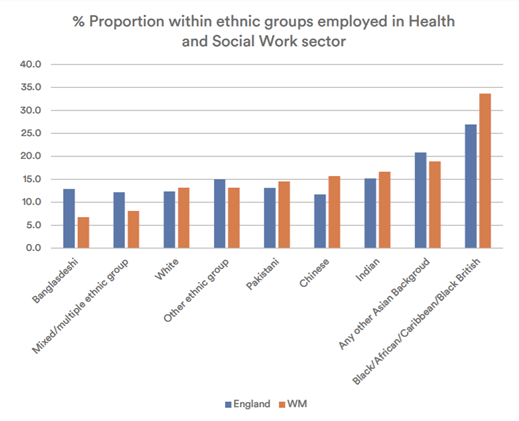

As far as occupational inequalities are concerned, a recent study by Public Health England that is highlighted by the West Midlands Regional Health Impact of COVID-19 Task and Finish Group finds that certain occupations such as social care, nursing, taxi and bus drivers as well as security guards have the highest increased health risk due to Covid-19 exposure (Public Health England, 2020b).

In terms of disparities within the transport sector, PHE’s review shows that Bangladeshi ethnicity drivers face twice the risk of death than White drivers whereas Pakistani drivers face a range of 10-50 per cent of higher risk of death in comparison with White British drivers. In our region, the Pakistani ethnic group has the largest proportion within its population working within the transport and storage sector (17.2%) followed by the Bangladeshi ethnic group (15.5%) and therefore have a greater risk as population groups of being exposed to the infection (WMCA, 2020).

Ethnic groups employed in Health and Social Work sector, England vs. West Midlands – Source: WMCA, 2020As shown in the figure above health care system in the West Midlands region consists of a significant proportion of workers from Black and other Asian background, respectively by 34 per cent and 19 per cent (WMCA, 2020).

Evidence of systemic challenges faced by BAME staff in the NHS reveals that nationally 29 per cent of BAME staff and 24.2 per cent of white staff reported being harassed, bullied or abused by other staff during 2019. A valid concern here is that three Trusts in Birmingham and the Black Country were identified as being amongst the worst-performing nationally (NHS BAME Network, 2020). Most recent findings by Public Health England confirm that racism and bullying at work were significantly correlated with BAME staff’s reluctance to put themselves out when they faced PPE challenges (Public Health England, 2020b).

References

IPPR. (2020). Ethnic inequalities in Covid-19 are playing out again – how can we stop them?

NHS BAME Network. (2020). NHS Black and Ethnic Minority Network Taskforce: West Midlands Inquiry into COVID-19 Fatalities in the BAME Community.

Public Health England. (2020a). Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19.

WMCA. (2020). West Midlands Regional Health Impact of COVID-19 Task and Finish Group: Interim Report and Call for Evidence.

This blog was written by Dr Deniz Sevinc, Research Fellow for City-REDI / West Midlands REDI

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.