In this blog, Rebecca Riley, Administrative Director, City-REDI / WM REDI looks at the long term health impacts of the Coronavirus pandemic.

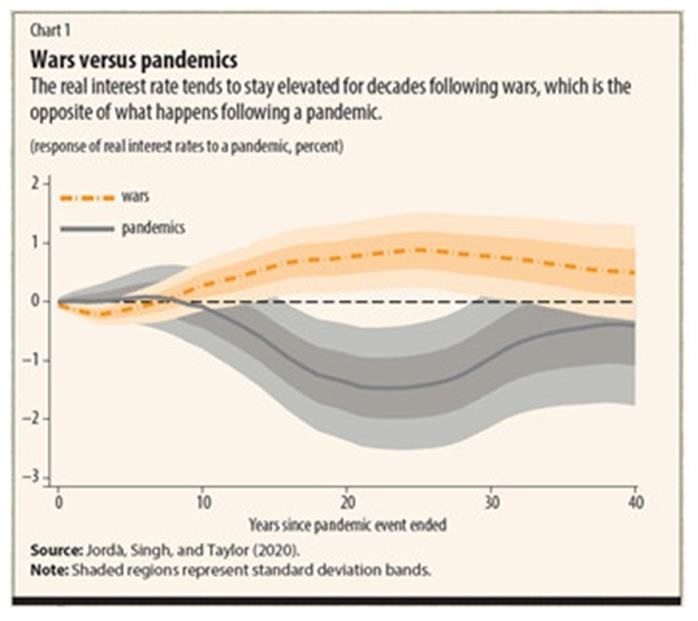

At the moment we are dealing with the short term impacts of the pandemic and the effect of the interventions that are being put in place and this is potentially only the beginning of the story. Earlier in the pandemic, I did a review of the 1918 pandemic and the effects it created. A lot of those warnings from history are unfolding now. As the IMF highlights whilst the rapid unravelling of production, trade and employment may be reversed long term consequences could persist for a generation. Pandemics have long term economic impacts which can be seen by examining interest rates, following a Pandemic the natural rate of interest is tilted down by nearly 1.5 percentage points about 20 years later. That’s a dip from the mid-1980s until today. And it takes 20 years for it to return. If pandemics are compared to wars, another economic shock the reverse can be seen as below. Pandemics are associated with subsequent low returns on assets and this might be due to lack of needed investment or desire to save (as we have seen in the last 6 months).

This could be prevented in this pandemic, through the use of modern medical care to keep the death toll down. Low-interest rates impact on the elderly who are more likely to save. Most importantly the aggressive counter pandemic fiscal action will boost debt and force pressure on interest rates. On balance, this might mean a period of low-interest rates which provides governments space to mitigate consequences. Previous pandemics have led to increased inequality, with higher death rates in poorer communities and ethnic minorities. We are seeing this now, through a combination of the types of jobs they hold, the housing they live in and levels of deprivation and access to services which they suffer. There have been significant gender-based impacts with high rates of furlough, redundancy, exposure risk through occupation and increased childcare demands. Longer-term these effects could shift the role of women and disadvantaged groups, could constrain growth in diversity and create longer-term mental health issues.

The impact on the working-age population and their ability to work suffered significant impact in 1918 and tore at the social fabric and world of work. We are seeing that today with the changes in working from home creating an advantage for the higher-skilled but forcing other industry workers out. The fear of catching the virus is dramatically changing consumer behaviour and we have yet to see if it will return. Cities are suffering more and the beginning of division in communities are starting to emerge along with reaction to the interventions.

Long COVID

Negative impacts on health reduced life expectancy and what we are beginning to see emerge now is the concept of ‘long covid’. Today’s longer life spans may mean the long term impact will be different. As older people are disproportionately affected, although they are less likely to be in the workforce their spending power is higher and they save more. However, we know very little about the impact of long covid. In some patients, the post-viral illness continues for weeks and months. But there is a wide variety of symptoms which doctors racing to produce guidelines on.

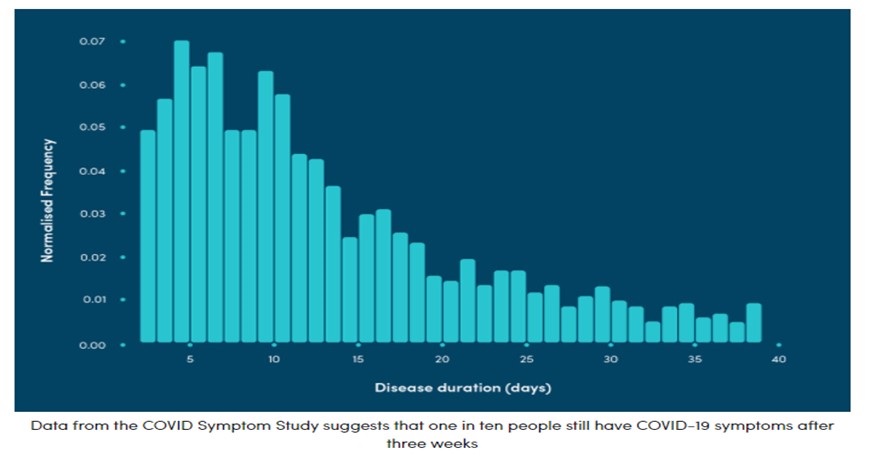

Data from the UK covid symptom study shows that most people recover within 2 weeks, however, 1 in 10 (see bar chart below) still experience symptoms over a longer period. A third of doctors are treating patients with symptoms believed to be a longer-term effect of Covid-19. A study in Rome has shown 87% of discharged hospital patients have symptoms months later and 50% had fatigue. The Covid app showed 4m people had symptoms after 30 days and 1 in 50 had symptoms after 90 days.

Symptoms include fatigue, palpitations, low mood, anxiety, headaches, coughs, loss of smell, delirium and ongoing shortness of breath. The research suggests that people with initially milder symptoms are more likely to have long term symptoms that come and go. There can also be significant long term cardiovascular and gastrointestinal distress and other organ issues. Evidence is emerging that it not only affects the lungs but also affects the brain, liver, kidneys, heart and blood vessels. 1 in 5 hospitalised patients suffers from a heart injury.

One review found about 40% of seriously ill Covid-19 patients in China experienced arrhythmias and 20% experienced other cardiac injuries. Those patients are more likely to die (51%).

Doctors also are reporting a growing number of Covid-19 patients with symptoms of neurological damage, including brain inflammation, seizures, and hallucinations. Health experts originally were telling patients to avoid seeking care at hospitals unless they had common Covid-19 symptoms such as a fever, cough, or trouble breathing, neurologists are hoping the new data will add neurological symptoms—such as confusion, numbness, or trouble speaking—to that list.

Kidney damage also is becoming a commonly reported issue among Covid-19 patients. Alan Kliger, a nephrologist at the Yale School of Medicine, said early data showed 14% to 30% of ICU Covid-19 patients in New York and Wuhan, China, lost kidney function and later required dialysis. The new coronavirus also appears to produce blood clots that can travel from patients’ veins to their lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism, and other organs. According to STAT News, Chinese researchers in one report said they found small blood clots in about 70% of the patients who died of Covid-19 and were included in the study. In comparison, the researchers found similar blood clots in fewer than one in 100 patients who survived the disease.

Clinicians and researchers have yet to determine whether the new coronavirus is directly attacking those organs, or whether the injuries are caused by the patients’ immune responses to the infection. Doctors say that researchers should also investigate whether organ damage and failure is being caused by medication, respiratory distress, fevers, the stress of hospitalization, and so-called “cytokine storms”.

People with these symptoms are struggling to get back to normal life, going back to work and they are not performing at the top of their game.

In summary

- Most people recover from mild COVID-19 within two weeks and more serious disease within three weeks

- Some people suffer from the effects of the virus for much longer

- The virus may cause damage to internal organs, resulting in long-term or potentially permanent health problems

- There currently is little information and support available for people with long-term COVID-19.

- We need to gather ongoing data about the nation’s health to understand the long-term effects of this disease.

These symptoms could affect more and more of the population as the pandemic continues, which stores up long term effects on the workforce, businesses and individuals. Many sufferers describe recovery followed by the illness roaring back.

The prolonged debilitating impacts from previous pandemics could be seen for decades after the initial infections. This virus is also showing early signs of significant long term health impacts which could knock onto the workforce and economy and as yet we have no data on what will happen. This will prolong the economic impacts as the impact and the knock-on impacts on the healthcare system dealing with these hangover effects.

This blog was written by Rebecca Riley, Administrative Director for City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham