Rebecca Riley looks at back at the Spanish Flu of 1918, who the virus affected, and what the short and long term impacts were for different countries.

The 1918 ‘Spanish’ flu, although it was a different virus to COVID-19, had similar wide-ranging pandemic effects. Transport and travel were far less common, the global population and average age of death are double what it was in 1918, but the spread was similar and as damaging. The pandemic had 3 peaks, one in spring 1918, a second more deadly one in autumn and a third in the following spring. In fact, the pandemic took 2 years to end, and estimates range from 2.7% to 5.4% of the world population (50m to 100m) died. Poorer countries were also hit harder with death rates double those in more developed countries.

The 1918 pandemic hit the 20 to 40 years olds harder (the working-age population). It is suspected that this was because of raised immunity in the older generation due to an earlier pandemic (Russian Flu) which many older people experienced. It also hit men harder than women, apart from pregnant women, where miscarriage was common.

Reviewing the impacts of the 1918 influenza pandemic a number of patterns emerged:

- Life expectancy dropped and negative impacts on health were abrupt and damaging.

- Although a pandemic is democratic and can affect everyone it’s not egalitarian, there were higher death rates in poor, disadvantaged communities. Poor sanitation, crowded living conditions and lack of access to health care all exacerbated death rates.

- There were no antibiotics which prevent deaths by secondary infections today.

- Global health systems were less developed and the population suffered extreme poverty, and many countries had spent any resources on the war.

Social impacts:

- This pandemic happened during WW1 and as such, many countries suppressed reporting. The virus is suspected to have started in the USA but because Spain was neutral during the war, reporting there was not censored which created the perception the country being especially hard hit by the pandemic and that it was the source of the virus. Information on prevention was also suppressed in many countries.

- The impact on the working-age population increased the impact on the social fabric and the world of work.

- Fear of catching the flu changed behaviours and dramatically altered social interactions. Authorities discouraged social interaction which fed rumours of enemies spreading the virus and created a climate of suspicion and distrust that characterised the period and long after. A greater death rate increases the levels of distrust, and this was a permanent change.

- In Spain, where the government and health care services proved to be ineffective, this distrust grew and led to more division in society, whereas Italy re-established solidarity and purpose and saw it as overcoming a difficult test as a nation. Mistakes and failures in managing the flu had long-lasting negative economic consequences.

- Cities suffered more than rural areas in general, but there was a large variation in cities. Newly arrived immigrants tended to die more frequently than older better-established groups.

- The impact on the adult population left significant issues with orphaned children, and elderly to fend for themselves. The deaths were seen as an apparent lottery. Only later did patterns emerge, with variability attributed to inequalities of wealth and social status or caste, and to an extent this was reflected in skin colour. Bad diet and crowded living created an environment where the poor, immigrants and ethnic minorities were more susceptible to infection.

- Underlying conditions left a person more susceptible to the flu, and remote communities felt the effects more severely due to lack of previous exposure.

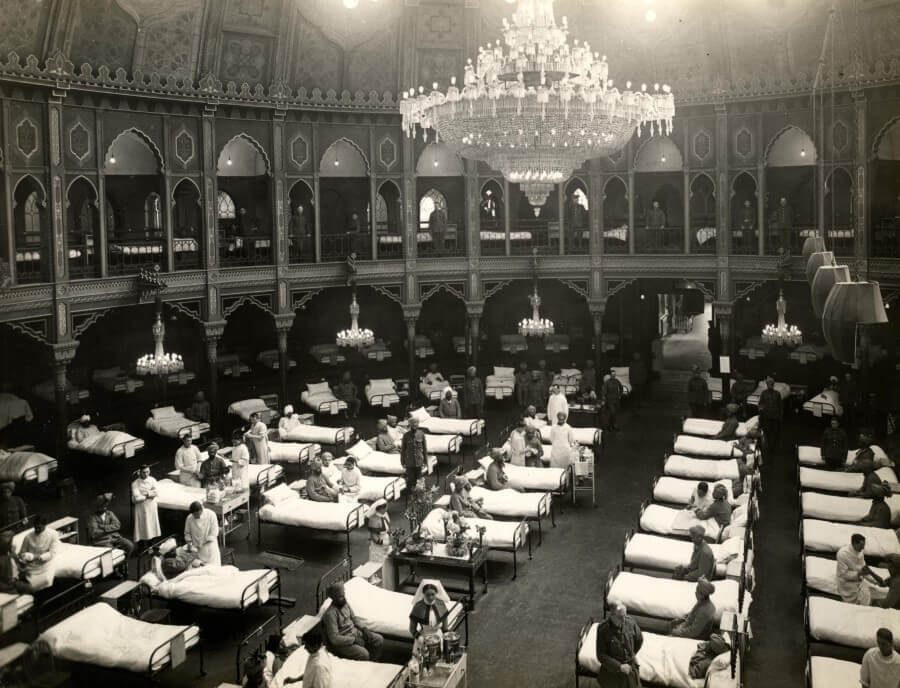

- Public health campaigns made a difference, social distancing was employed, with quarantine zones. Isolation wards and prohibition of mass gatherings. Australia kept out the more deadly autumn wave through closing its ports.

- Failing countries collapsed, Persia lost between 8-22% of its population. 8% equated to 20 times the losses in Ireland.

- At the time losses were seen as natural selection or competing races, emphasising the constitutional inferiority of some groups. This was seen in India, where there were 18m losses and the under-powered response by the British government fuelled backlashes and triggered protests.

- It also prompted a wave of workers strikes and anti-imperialism, a reaction to rising inequality.

City-REDI / WM REDI have developed a resource page with all of our analysis of the impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on the West Midlands and the UK. It includes previous editions of the West Midlands Weekly Economic Monitor, blogs and research on the economic and social impact of COVID-19. You can view that here.

This blog was written by Rebecca Riley, Business Development Director, City-REDI / WM REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.