When I joined City-REDI in October, I was seconded 50% of my time to the Smart Specialisation Hub in Islington for six months. The Hub provided analysis to improve local and national understanding of innovation capabilities, benchmarking innovation activity across Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs).

When I joined City-REDI in October, I was seconded 50% of my time to the Smart Specialisation Hub in Islington for six months. The Hub provided analysis to improve local and national understanding of innovation capabilities, benchmarking innovation activity across Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs).

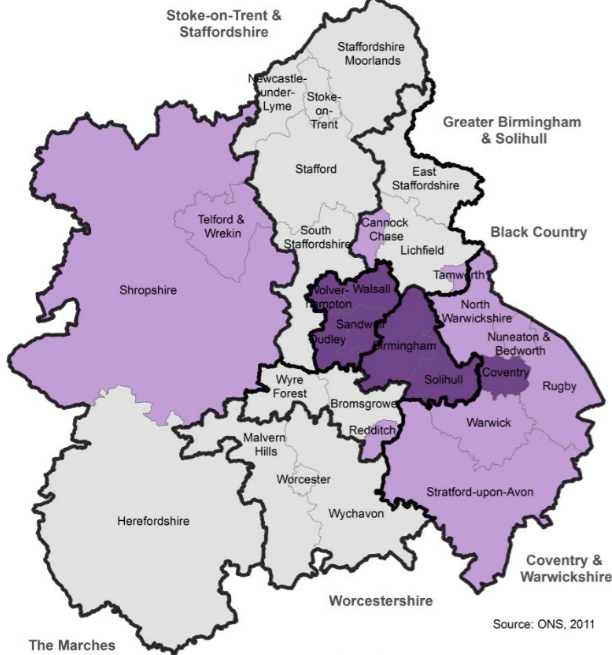

Established in 2010 by the then Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, LEPs are business-led partnerships linking the private sector, local authorities, higher and further education and the voluntary sector to drive growth strategically in local communities. Thirty-eight LEPs exist across England, with three covering the West Midlands: Black Country; Coventry and Warwickshire; and Greater Birmingham and Solihull.

My main project during my secondment was producing a report examining external funding at LEP level. I mapped the value of different funds awarded directly to LEPs and other organisations in LEP areas such as universities, showing how much money goes into supporting innovation and growth in each area. This enabled me to identify trends in the areas, which were most successful in securing external funding as well as to understand better why some LEPs were outperforming others in terms of the value of funding secured. In this blog, I pick out some of the key conclusions from the research.

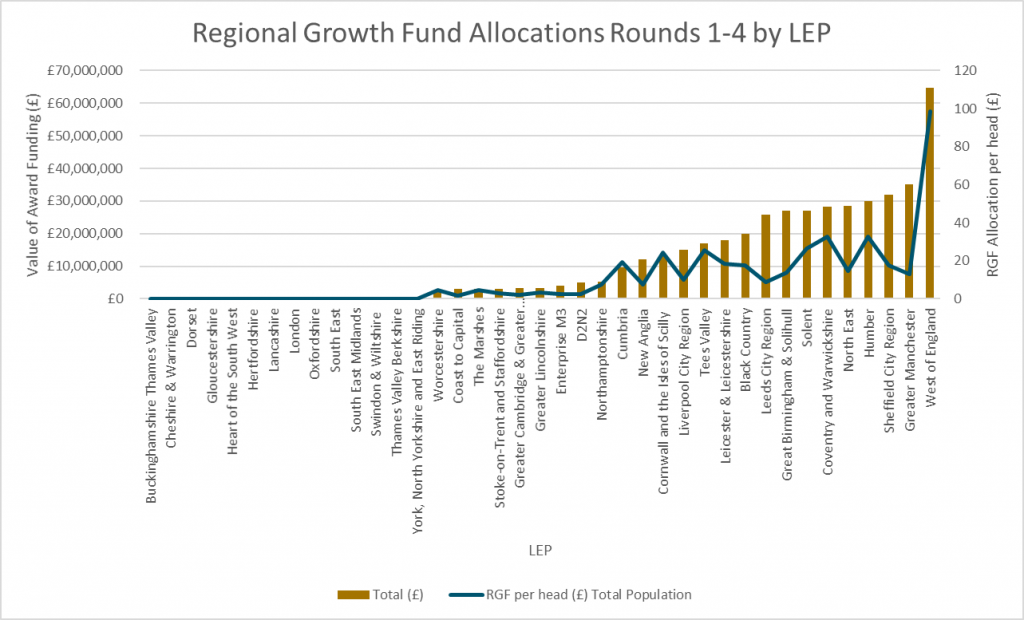

Large urban LEPs most successful in obtaining central government funding

In addition to core funding for staff, admin, strategy development and implementation costs (currently £500,000 per LEP per year), LEPs have also been eligible to apply for central government funding. My analysis revealed that the LEPs, which have performed strongly in terms of total allocations for central government funding such as the Regional Growth Fund, the Growing Places Fund and the Growth Deal, are Greater Manchester, London and Leeds City Region. Small, rural LEPS struggle the most to obtain funding. Whilst Greater Manchester stands out outside of London, combined funding for LEPs in the West Midlands is very similar with a similar population.

Figure 1 below demonstrates allocations from the Regional Growth Fund, established to help “areas and communities at risk of being particularly affected by public spending cuts”.

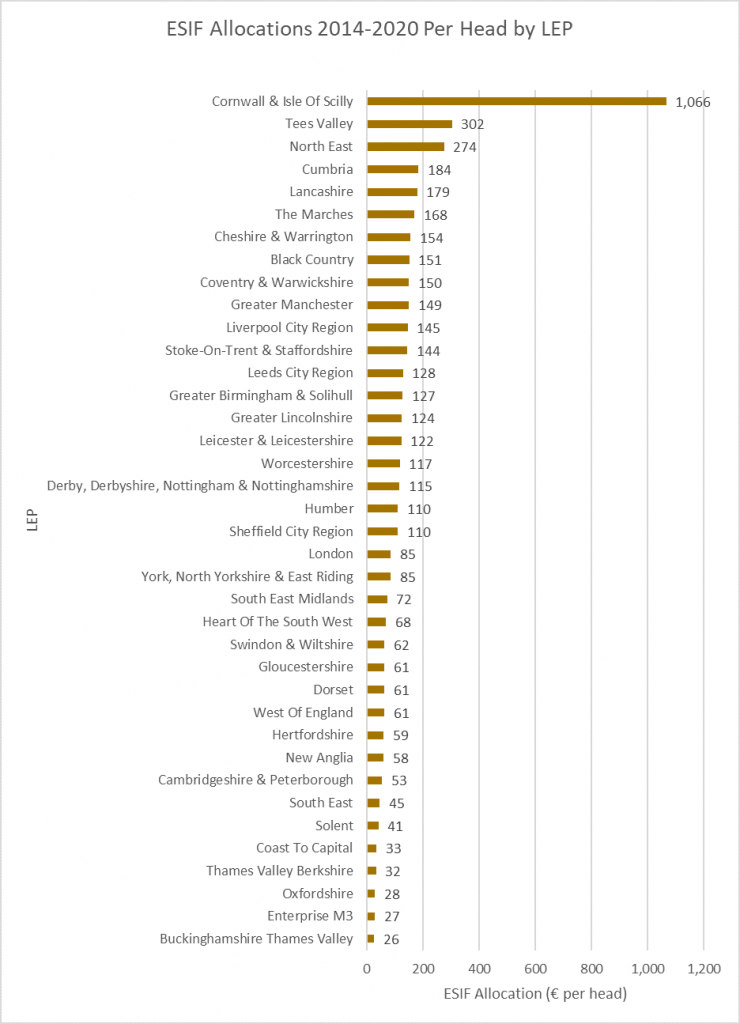

Importance of European Structural and Innovation Funds (ESIF) in the Midlands

The report shows the importance of ESIF funding, particularly the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund, in supporting economic growth in LEP areas.

LEPs are responsible for designing and delivering strategies concerning how to best use ESIF. Central government then manages the funds (House of Commons Library, 2017; HM Government, 2013).

ESIF allocations are based on notional funding allocations for each region within the 28 European Union member states. The European Commission categorises regions according to their per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as either ‘less developed, ‘transition’ or ‘more developed’. This explains why Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly received the largest allocation in terms of total grant and grant per capita. It is the only English region, categorised as ‘less developed’ due to having a per capita GDP of less than 75 per cent of the EU average.

ESIF funding stands out in Figure 2 in how it provides high per head allocations to areas with low per capita GDP rates (such as The Marches, Lancashire, Cumbria and the Black Country), not prioritised in the other schemes.

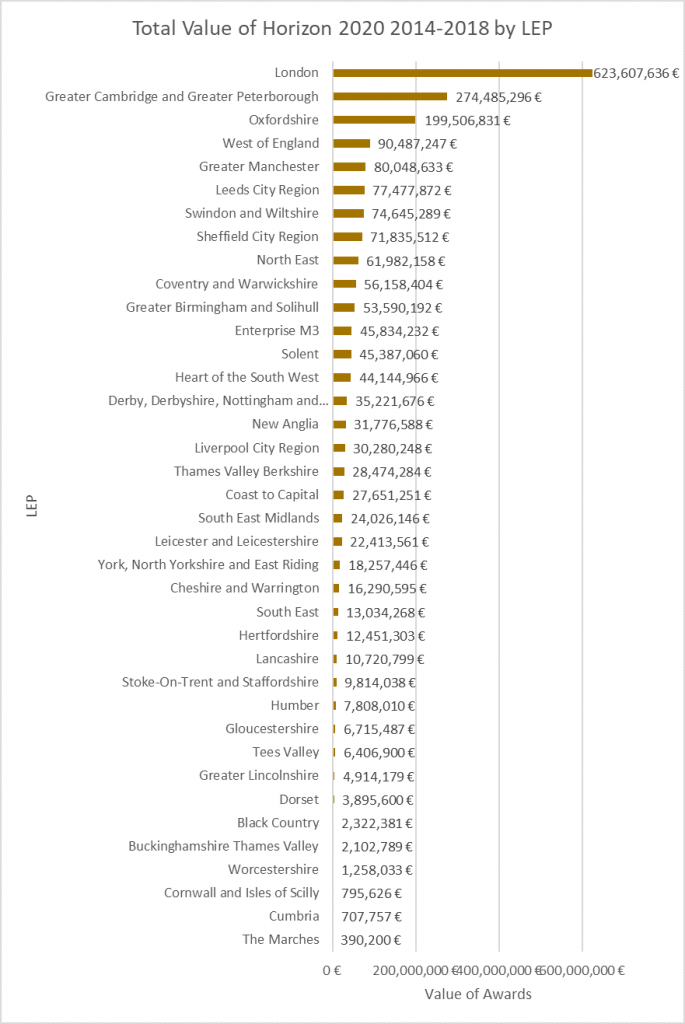

Importance of research-intensive universities

Having one or more research-intensive university is central to which areas have received the highest awards for Horizon2020 and research Council/Innovate UK funding. For example, of the 10 LEPs awarded the highest number of Horizon 2020 grants, 8 have at least one Russell group university (the 24 leading research universities in the UK). Indeed, these 10 LEPs include 14 of the 20 Russell group universities in England. The majority of applications are awarded to Higher Education Establishments – 57%; followed by private for profit companies – 28%; research organisations – 9%; other organisations – 4%; and public bodies – 3% (Figures do not add up to 100% due to rounding). Figure 3 below shows the value of funding awarded by Horizon2020 to organisations within each LEP 2014-2018. This emphasises the crucial role universities play in local economic development.

After analysing trends in the value of external funding secured by each LEP, I conducted qualitative interviews with key decisions makers in 13 LEPs across England to investigate issues revealed in the survey in depth. My questions focused on how LEPs perceive their role in terms of obtaining external funding, the challenges they face regarding funding as well as the strengths of approaches adopted in different areas.

Role of LEPs in external funding

I found that LEPs do not consider obtaining external funding to deliver projects in their local areas to be their central role. Indeed, many feel this represents a distraction from their principal aims. One urban LEP stated:

“Maybe it’s a misunderstanding of LEPs generally out there in the policy community, but I don’t think that’s actually our role to win and secure funding”

Instead, LEPs described having an important role in delivering funding for their areas through leadership and partnership. However, as the report explores, the LEPs interviewed differed in how they conceive of the extent to which LEPs are responsible for strategy design, implantation and support. The report suggests four different types of LEPs can be identified: direct action LEPs; collaborative, partnership LEPs; convening, supporting LEPs and internal challenge LEPs.

Key challenges regarding funding

LEPs interviewed reported experiencing challenges related to staffing, the amount of central government funding available, access to match funding, existing outcome/output requirements, alignment between different funding pots, governance arrangements, data evaluation and the ability to implement cross-LEP projects.

To look at just a few challenges in detail:

- Central government funding – LEPs revealed concern over a lack of clarity regarding future funding, suggesting this is starting to impact on LEP projects and strategic planning. Details of the Shared Prosperity Fund designed to replace ESIF funding (likely to cease following Brexit) and reduce inequalities between communities across the four UK nations are yet to be released despite being included in the 2017 Conservative manifesto, being proposed by government in 2018 was due to be released before the end of 2018.

- Staffing – some larger LEPs described challenges paying staff competitively given the core LEP staffing budget is the same regardless of the size of the LEP. Participants suggested limited staff budgets in turn constrain the activities of LEPs to bid for funds. Nonetheless, larger LEPs, particularly those with combined authorities suggested they had greater networking capacity, which helped not them just in terms of understanding the expected content of bids, but also in finding out additional information regarding expectations and exploring options for funding when bids were not successful.

- Governance – the establishment of combined authorities appears to have posed difficulties for some both with and areas without a combined authority. One LEP in a combined authority area suggested structures were “disjointed” and that it was taking time to identify assurance processes and the key responsibilities of the Combined Authority and LEPs. Another LEP implied areas without a mayoral combined authority suffer in terms of funding allocations.

Looking Forward

LEPs clearly operate in a complex and rapidly changing environment. This project has shown it is very important that LEPs and Combined Authorities are given sufficient time to establish their structures and core responsibilities to maximise their impact and long-term outcomes. Given the value of funding from ESIF, it is important that clarity on future central government funding be provided to LEPs soon. Whatever grant regime replaces the European Regional Development and the Growth Deals, should also make it easier to implement cross-LEP projects, as innovation is highly dependent on networking.

This blog was written by Dr Abigail Taylor, Data and Policy Analyst, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

1 thought on “The Realities, Challenges and Strengths of the External Funding Environment at LEP Level”