Donald Houston and Iain Docherty highlight that insufficient attention has been paid to the regional implications of economic policy choices such as Brexit, which has hampered efforts to address place-based inequalities. This blog was originally posted on the UK in a Changing Europe website.

For almost a century, the UK policy system has – with decidedly limited success – grappled with the implications of its highly regionally imbalanced economy. The latest iteration of regional policy aimed at fixing this imbalance is the government’s flagship 2019 manifesto pledge of ‘levelling up’ the regions. But for almost as long as there has been an explicit (narrative about) regional policy, actual policy decisions have worked against reducing the gap between regions.

Decisions

Systemic decisions – including the concentration of public research and development spending in the ‘golden triangle’ and the failure to decentralise central government jobs meaningfully – that concentrate the political economy of the UK so strongly in and around London fail to recognise that national economic performance relies on each region doing well.

Challenges

Each of these regional economies has its own unique set of challenges and opportunities. As long as national economic policy regards regional policy as a market ‘correction’, ameliorating the worst excesses of spatial inequality rather than as essential to growing the economy, then genuine levelling up will remain a pipe dream.

That the economic debate so often focuses on abstract metrics and national data, which tell us little about what is happening in any real place, hasn’t helped. Much better sub-national economic data are crucial to understanding what is really happening across the UK economy, and making better decisions.

The geographical illiteracy of the national economic debate is especially apparent when it comes to Brexit. Analysis of Brexit has seen precious little discussion of its differential regional impacts, and how they have manifested themselves in the real economy of specific places. And Brexit has been remarkably absent from the levelling up debate, which has emphasised rebuilding ‘pride in place’.

Since the Referendum

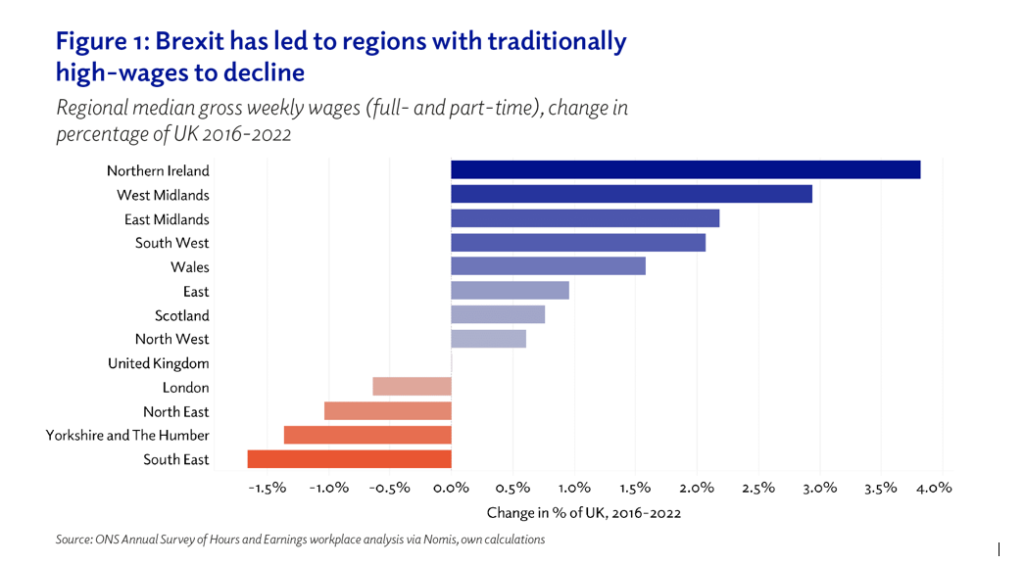

Since the Brexit referendum in 2016, there have been surprising shifts in the economic performance of some regions. Over this period, COVID-19 has affected trends and data collection, and differences between regions in the size of the public sector and industrial composition are also important. Nevertheless, shifts at regional level since the Brexit referendum are striking. Northern Ireland, long one of the UK’s economically weakest regions, has improved the most relative to the UK on earnings (Figure 1).

The South East, the second strongest region, has fared the worst relatively. London, despite having had substantially higher wages and stronger wage growth than any other region before Brexit, has declined slightly too, along with the North East and Yorkshire & The Humber. As Sadiq Khan has pointed out, perhaps the capital’s exposure to Brexit uncertainty over financial services and reliance on EU workers has been at play.

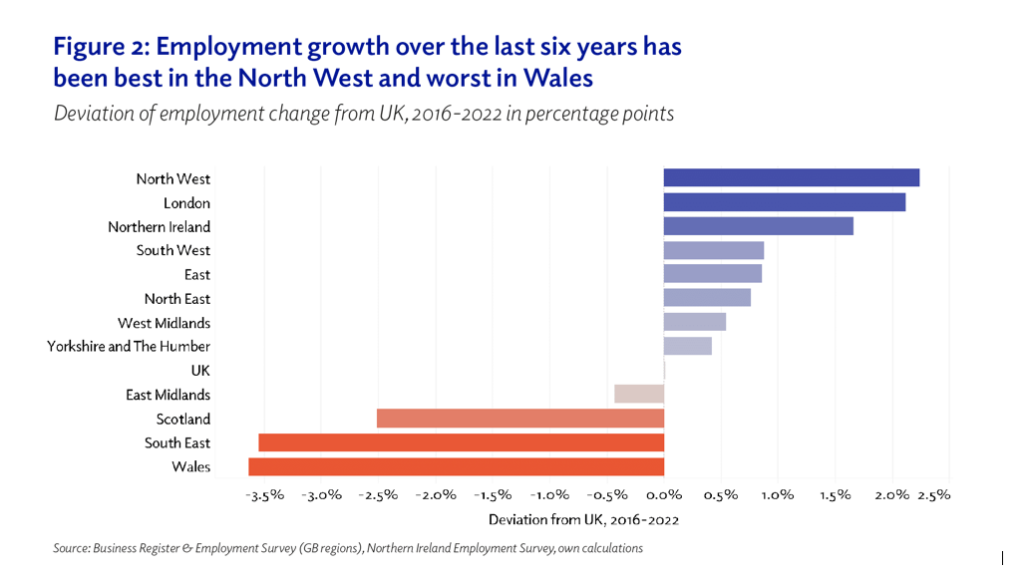

Turning to employment growth, the North West comes out on top (Figure 2). In the second place, London has continued to pull away from the rest of the UK, in contrast to its relative decline in earnings. Northern Ireland also does well on employment growth, ranked in third place.

The regional rankings in Figures 1 and 2 are important given that 99% of the writing about the economic and (potential) constitutional consequences of Brexit have been in the abstract terms of economic growth, fiscal autonomy, trade, currency, and so on.

Whenever the Brexit debate has moved beyond the abstract, it has tended to focus on symbolic sectors with relatively little economic impact, such as fishing which accounts for only 0.03% of UK economic output (or 0.2% of Scottish economic output for that matter). But voters tend to think about jobs, wages and the cost of living, hence the now infamous heckle that “that’s your bloody GDP, not ours”.

The notion that the UK comprises a number of regional economies, and that they would be differentially impacted by Brexit, failed to gain much traction. The Scottish government put forward a compromise position on Brexit highlighting the importance of single market access, but other than the London Mayor’s interventions, that was largely it.

But the differential performances of Northern Ireland and London raise an important question that hasn’t had sufficient attention.

What exactly is the wider spatial impact of Brexit?

Northern Ireland’s unique status in terms of access to both the UK internal market and the EU single market for goods has been at the heart of UK-EU relations since Brexit. Although the politics of the Protocol have been rather difficult to say the least, it does appear to have precipitated a recovery in earnings and employment growth compared to the UK average.

Brexit gives special poignancy and voice to Northern Ireland, but it is striking that many of the debates around the Protocol and Windsor Framework were, in fact, essentially economic ones.

Despite the obvious distinctiveness of Northern Ireland, it is worth thinking about why other regional economies in the UK aren’t stimulating similar debates about what Brexit means for them.

From time to time, there are hints that discussion about the ‘economic case for independence’ in Scotland might extend beyond fiscal- and currency issues to encompass whether the UK or European markets offer the best prospects for growth, inward investment, wages and therefore the capacity of the Scottish economy to deliver an improved standard of living.

Indeed, with the new First Minister admitting independence isn’t coming soon, perhaps the next phase of constitutional politics in Scotland might be about how to engineer a move back towards the single market (and customs union).

What needs to be done?

All across the UK, there needs to be more attention given to regional economic distinctiveness, especially if levelling up is going to be more than a slogan, because the data show that differences remain stark.

But as yet, there are precious few signs of anything comparable in England to debates in Northern Ireland and Scotland (and to a lesser extent in Wales) about how Brexit has affected the capacity for the regions to be anything other than economic bit players compared to London and the wider South East.

This blog was written by Donald Houston, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham and Iain Docherty, Dean, of the Institute for Advanced Studies and Professor of Public Policy and Governance, the University of Stirling.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.