In a series of blogs, Simon Collinson, Fumi Kitagawa and Tomas Ulrichsen examine the role of universities in regional development.

The blogs are co-authored by the Policy Evidence Unit for University Commercialisation and Innovation (UCI) at the University of Cambridge Institute for Manufacturing (IfM) and the West Midlands Regional Economic Development Institute (WMREDI at City-REDI), University of Birmingham.

In the third blog from the series, Tomas Ulrichsen discusses how universities can invest in their innovation and wider knowledge exchange activities to boost the innovation performance of their regions for the benefit of their local communities.

Read the other blogs from the series:

Place Matters: Universities and Local Innovation Systems

Enhancing University Contributions to Local Growth by Targeting High-Potential Firms and Industries

Universities’ Role in Helping Regions Transition From Legacy Industries Into New Areas

The UK government has set ambitions to reduce the significant disparities in economic and societal prosperity that exist across the UK to increase the opportunities and life chances for all UK citizens. Tackling the long-standing productivity challenges facing the country and unleashing the economic potential of towns, cities, and rural communities. Places that have, for too long, been left behind the most prosperous parts of the UK, many of which are located in the Golden Triangle between Oxford, Cambridge and London.

In the first blog from this series, we argued that the solution in parts of the country will require investments in strengthening the regional innovation system to enable it to not just create new sources of value but also to raise its ability to appropriate more of this value locally. With universities often one of the largest employers in their local economies, and organisations that provide some of the critical knowledge-based resources for innovation to thrive, university research and knowledge exchange (KE) funders such as Research England (part of UK Research and Innovation), university leaders, and local governments and others, are being challenged to find ways of better mobilising the university system to help deliver on these important ambitions.

In early October 2023, the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology announced a new pilot Regional Innovation Fund to enable universities in weaker regions to better contribute to delivering this agenda. It provides £60 million to universities to support local innovation, commercialisation, and economic growth, with the funding prioritising regions with lower R&D investments and universities with strengths in delivering local growth and regeneration activities. In England, this funding is being channelled through Research England.

The arrival of this additional funding raises important questions for funders and university leaders alike about how, in practice, universities can invest in their innovation and wider KE activities to boost the innovation performance of their regions for the benefit of their local communities. Below we set out some thoughts.

Generating innovations and creating potential value for their region

Perhaps the most talked about roles of universities in unleashing regional innovation centres on their contributions to the generation of new innovations, typically through their research, and research-related KE activities (Kitson, 2019). This includes, for example, building global centres of research excellence in key technology areas (e.g. quantum, artificial intelligence, energy technologies, and bioinformatics and genomics), working closely with large, R&D-intensive companies on their next-generation products and services, and commercialising breakthrough technologies and ideas through spinouts and IP licensing activities.

These activities help to create seeds of potential value that need to be invested in and further developed to translate these opportunities into economic value. In many cases, much of the downstream value realised from these activities will be outside the university’s local economy, and often overseas. Once a critical mass is reached, these activities can become an important factor in the development and success of high-technology clusters (as it has been for Cambridge), helping to attract inward investment, talent and other key resources to the area.

Strengthening the ability of a region to appropriate value from innovations

This ‘innovation generation’ focus on universities’ roles in regional economic development is only part of the story. The ability of a region to appropriate value from innovation is critically important for ensuring local communities realise benefits from innovation. In the first blog, we noted that a critical mass of local firms with sufficient capabilities to exploit knowledge and translate it into value-adding opportunities for the business is crucial here. We set out a framework capturing many of the key factors that can help to deliver this, not least:

- Strong local institutions and governance;

- Availability of general and innovation-specific infrastructure, amenities and support;

- A dynamic labour market and skills base;

- A vibrant knowledge base;

- The strength and availability of local supply chains and complementary assets;

- The attractiveness of the area and quality of life.

Firms also benefit from being part of a cluster which, among other things, can facilitate the diffusion of ideas, knowledge and talent. Our first blog highlighted that the development of local areas is often strongly path-dependent, with strong effects of legacy investments and existing capabilities.

In all these areas, universities have the potential to contribute. Over the past few decades, we have seen universities across the UK become much more active in helping local firms – particularly Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) – to build up their capabilities to innovate and realise value from innovation. Examples include the emergence of KE initiatives providing technical and management training; helping companies to identify new opportunities for innovation and open up new market opportunities; helping companies to demonstrate, test and launch their innovations; helping partners to adopt the latest technologies and processes; and working together to solve technical problems hampering their innovation efforts.

We also see universities working with local partners – including, for example, local government, business groups, innovation support organisations, and other education providers – to strengthen the underpinning conditions and improve the resources available for innovation in the area (Ulrichsen and Kelleher, 2022). Examples here include (co-)investing to build innovation districts, incubation and scale-up spaces; seeding networks to better connect different organisations involved in innovation; leveraging their convening power to bring disconnected actors together around common challenges; and investing to better align skills provision with current and future local industry and innovation needs. We have also seen a growing involvement of universities in supporting the development of local innovation strategies and strengthening local efforts to attract inward investment to the region.

For many areas, it is these wider efforts that will be particularly important for delivering a step change in their local economic performance.

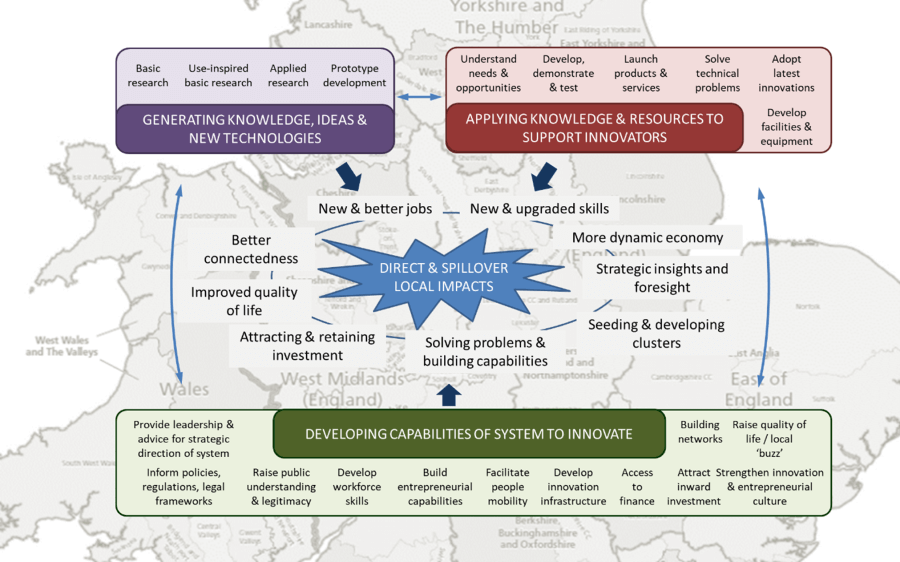

As FIGURE 1 below shows, the university’s contributions to regional innovation are multi-faceted, developing new knowledge and technologies, leveraging existing knowledge and resources to help innovators solve problems, and strengthening the innovation system by building the networks, infrastructure and capabilities to innovate.

FIGURE 1: University contributions to regional innovation

An increasingly strategic agenda for university leaders

A recent survey of university KE leaders showed that, when looking forward from 2021 to the economic recovery and future, most placed significant strategic importance on working within their local economies to increase innovation and economic prosperity locally (Ulrichsen and Kelleher, 2022). This was equally true of large research-intensive universities with global missions as well as more teaching-driven, regionally focused institutions. It was also one of a number of strategically important priorities.

Above we highlighted many ways through which universities can contribute to boosting local innovation. How a particular university will contribute will depend in part on its strategic ambitions and available resources and capabilities (including skills, knowledge bases, physical and digital infrastructures, social networks and partners etc.).

It will also depend on the specific conditions, opportunities and challenges in their local economies. Richard Lester – in his seminal work on university roles in local innovation systems (Lester, 2005) – showed how the industrial dynamics at play locally were a particularly important factor in shaping how universities contribute. He highlighted key differences between local economies seeding new industries, those working to attract industries from elsewhere, economies seeking to diversify into related markets, or those needing to upgrade to survive (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2: Differentiating university contributions to local economies undergoing different types of industrial transformation

| Type 1: Emerging Industries | Type 2: importation/transplantation of industries | Type 3: Diversification of existing industries into technologically related new ones | Type 4: upgrading of existing industries |

| · Forefront science and engineering research

· Technology licensing policies · Promote/assist entrepreneurial businesses (incubation services, etc.) · Cultivate ties between academic researchers and local entrepreneurs · Creating an industry identity o Participate in standard-setting o Evangelists o Convene conferences, workshops, entrepreneurs’ forums… |

· Education/manpower development

· Responsive curricula · Technical assistance for sub-contractors, suppliers |

· Bridging between disconnected actors

· Filling ‘structural holes’ · Creating an industry identity |

· Problem-solving for industry through contract research, faculty consulting, etc.

· Education/manpower development · Global best practice scanning · Convening foresight exercises · Convening user-supplier forums |

Source: Lester, R. (2005) Universities, Innovation, and the Competitiveness of Local Economies: summary report from the local innovation project – phase I, Cambridge, MA: Industrial Performance Center, MIT.

Crucially, it is likely that not all universities will be able to meet the full range of innovation needs of their local economy, particularly where they are larger and more complex. The diversity of universities in a region can be an important asset for improving the economic fortunes of the area.

We must appreciate that universities have very different knowledge bases, expertise and infrastructure which they can leverage to support different points along the innovation journey. For example, while universities like Cambridge and Oxford pursue large amounts of more fundamental research that push the frontiers of science and unlock breakthrough inventions, others have much greater capabilities in applied research, solving manufacturing challenges, and delivering product development/engineering solutions. Combined, they have the potential to provide a more complete and integrated set of support that can help partners not just seed new sources of value through innovation, but help them solve critical scale-up challenges and build the capabilities to anchor more of the value here in the UK and in a particular region.

Looking forward

Funders like Research England – whose remit is to create and sustain the conditions for a healthy and dynamic research and KE system in the English higher education sector, and allocate much of their funding via formula – are grappling with how to develop effective and targeted funding programmes to boost the regional innovation performance of weaker economies across the UK. One major challenge here is the lack of high-quality and up-to-date data and evidence on the scale of need, how universities contribute to their regions, what works in different contexts, and the impact of these efforts.

Research England (RE) has committed to developing its capability as a national centre for KE data, metrics and evidence to improve its ability to fund KE effectively, support the development and impact of the English university system, and demonstrate the value of the university system. This is being formally supported by the Policy Evidence Unit for University Commercialisation and Innovation (UCI) at the University of Cambridge, with Tomas Ulrichsen as National Adviser. In October 2023, RE’s Executive Chair, Professor Dame Jessica Corner asked that early attention be given to improving local and regional growth metrics.

For university leaders, there are important challenges around translating strategic priorities around supporting economic growth in their regions into actionable initiatives and activities on the ground delivering impacts. It will also benefit from greater efforts to better connect capabilities from different universities, innovation intermediaries, further education colleges, businesses large and small, local government, professional services and others, to drive a more coordinated and system-wide effort to boost innovation for regional economic benefit. This, however, takes resources and commitment from across the system to a common goal. Our survey of university KE leaders from 2021 suggested that most, while seeing strategic opportunities in this area, also believed they lacked the necessary financial and non-financial resources to do so. The pilot Regional Innovation Fund will help.

Wider research being undertaken by UCI is also finding that universities can struggle to adapt and reconfigure operationally to deliver on major new strategic priorities, particularly where these significantly push the boundaries of their more traditional focus. Here, we need greater ‘dynamic’ capabilities and tools at the university level to deliver strategic change.

This blog was written by Professor Simon Collinson, Professor Fumi Kitagawa, Chair of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham and Tomas Ulrichsen, Director of the University Commercialisation and Innovation (UCI) Policy Evidence Unit at the University of Cambridge.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.