It is not uncommon to hear that the UK is the most centralised country in the developed world. London utterly dominates the rest of the country to an extent that is quite remarkable. From politics to business, media to culture, the wealth and power of the UK is almost entirely within London’s orbit. Indeed, if London and its hinterland in the South East were for some reason to part ways from the rest of the UK (LonExit?), the effects would be quite dramatic. For one thing, what’s left of the British economy would be smaller than Russia or South Korea, falling from 5th largest in the world to 13th (Eurostat figures). The country would also lose far and away its largest city, its most significant international tourist destination, and the bulk of its infrastructure. The remains of the UK would also be required to make major decisions for itself – in some places a totally unprecedented development.

Decision-making power in the UK is jealously guarded by the central government in Westminster. Indeed, away from the parliaments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, it can be said that local government in the UK functions essentially as an extension of central authority. Scholars have identified the major reforms of local government in 1974 as the date when central government began fundamentally undermining the autonomy of local authorities. This domination of the centre by the periphery was illustrated in a 2011 report by the Institute for Economic Affairs, a right-wing think tank, which identified 1,300 statutory duties placed upon local authorities by parliament. So, with the arrival of new combined authorities in England and granting of additional powers to the Scottish Government following the independence referendum in 2014, what is the state of devolution in the UK today? And more importantly, what is the real point of devolution?

Devolution – a means to an end or an end in itself?

There are several reasons to pursue devolution and the decentralisation of policy-making. Firstly, local decisions can make use of local knowledge and adapt to specific conditions on the ground that a one-size-fits-all approach from Whitehall can’t adapt to. Secondly, bringing decisions closer to the level of the citizen can go some way to addressing the democratic deficit in the UK and helping individuals feel they can have a say over changes happening to their area.

What’s more, there is a curious contradiction in the British government’s encouragement of economic innovation among businesses while at the same time stifling opportunities for innovation among local authorities. Allowing for experimentation and diversity at a local level would create a “marketplace” of ideas, and a range of responses to significant policy challenges that central government has demonstrated it is unable to overcome, such as how best to respond to post-industrial economic decline or the integration of different communities. Successful interventions at the local level could inform areas with similar problems as to possible ways of tackling the issue. There is already evidence that the administrations of the devolved nations function as laboratories for new ideas. Consider for example the Welsh Government’s single-use carrier bag charge in 2011, which reduced the use of plastic shopping bags by 71% and has since been adopted across the whole of the UK.

There is also a significant economic dividend in devolution. Research by ResPublica estimated that devolving powers over council tax, business rates, infrastructure, planning, housing and skills to the ten Core Cities outside of London and the South East would generate an extra £222 billion in economic activity and create 1.16 million new jobs.

Local Industrial Strategies

One way of unlocking the economic benefits of devolution is through the formulation of Local Industrial Strategies (LIS) that are adapted to the strengths and challenges of an area. These are new policies that are produced in tandem by mayoral combined authorities and Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) to promote integrated working between the public and private sectors, as well as the coordination of local economic policy with national funding streams. The LEPs write these industrial strategies, which are subject to approval from central government; it hardly needs pointing however out that this could be seen as a further means of centralising power through committing local government to implement central government decisions.

Despite this risk, there is clearly a lot of scope for the Local Industrial Strategies to be beneficial for regional economies and populations. The government has acknowledged this, announcing in December 2018 that a “wave three” of LIS formulation will take place at an unspecified date in the future after “wave two” has been delivered in March 2020. This second tranche of LIS will be made up of policies for combined authorities such as the Tees Valley, West of England (Bristol) and North East (parts of the Newcastle conurbation).

“Wave one” comprised Greater Manchester, the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford corridor and the West Midlands. The documents are intended to drive productivity growth while also focusing on inclusive economic development – that is, ensuring all people benefit from growth in order to tackle the growing inequality crisis in the UK. They bring with them funding for housebuilding, infrastructure and investment in innovation as well as skills training. It should be borne in mind however that this is set against a context of austerity, which will be explored in a subsequent blog on this topic.

Case study: West Midlands

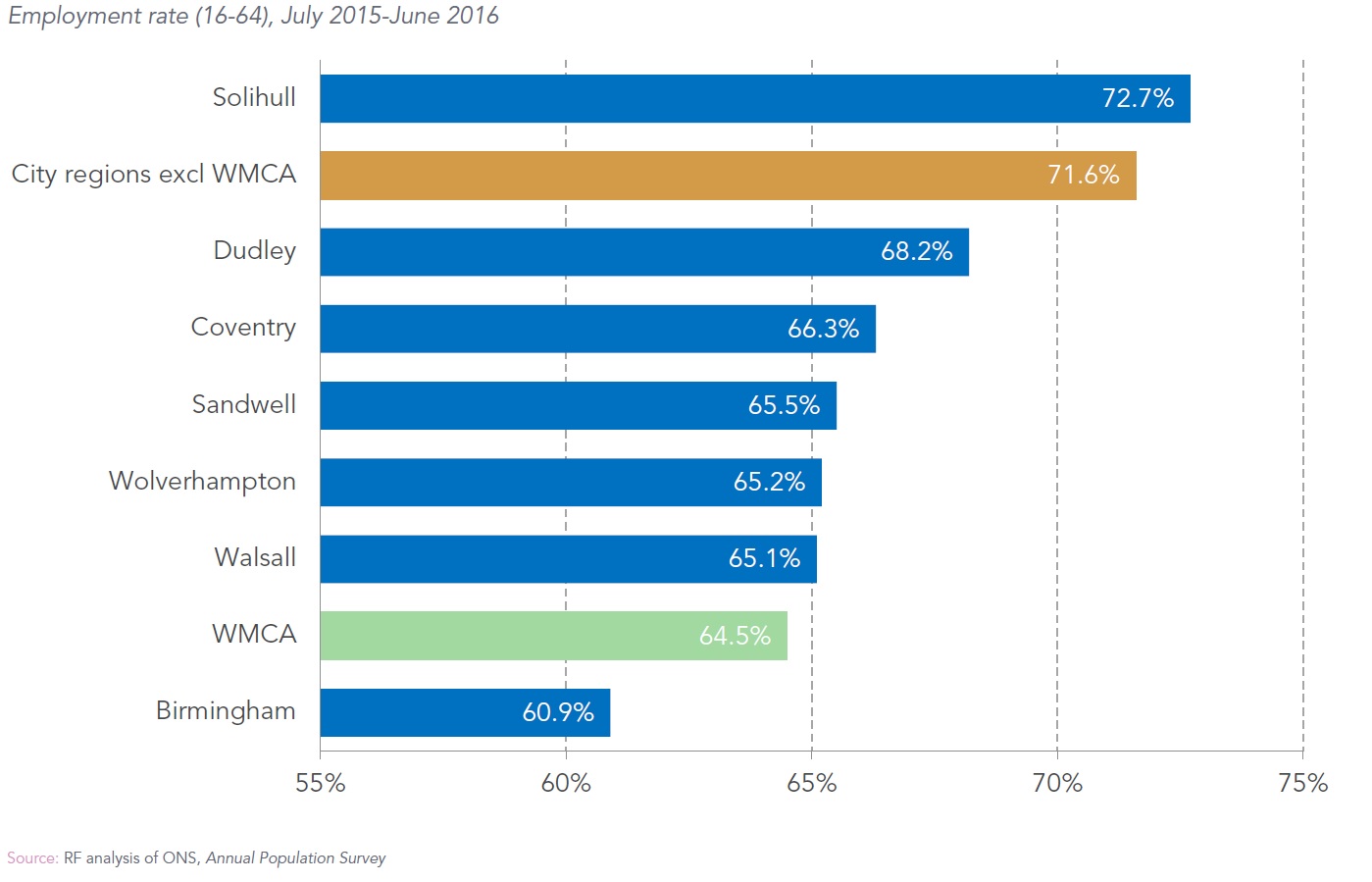

As the Resolution Foundation notes, from economic growth to income, the West Midlands underperforms not just the UK average but also other city regions, with a ‘particularly severe employment problem’. These are deep-rooted problems, with data showing little improvement in material wellbeing in the West Midlands prior to the crisis and during the subsequent period of austerity. It is therefore clear that the priorities of the new West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) mayor, as well as the LIS for the area, to tackle the twin challenges of employment and skills. There is a persistent shortage of higher qualifications and the employment rates of ‘low activity groups’ (BAME people, disabled people and those with low levels of qualifications) are even worse than the national average figures. Employment rates in the WMCA area have also improved the least of any city region since 2011.

While these challenges make for grim reading, there is a positive: the challenges faced by the West Midlands can easily be articulated, which means there can be a focus on getting people into work and helping them to develop their skills. To that end, adult skills funding has been devolved to the WMCA, and the combined authority has the chance to co-design employment support in the region. However, given the scale of the region’s employment problem it is clear that greater funding needs to be devolved, and schemes launched to target ‘low activity groups’ that have lower employment rates than they would in any other city region in England.

A final priority should be ensuring that there is ‘good work’ in the area that people can access. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation describes ‘good work’ as being about more than just paying the Living Wage Foundation hourly rate. It is also about offering flexibility, whether that means part-time work or allowing people to fit their work around caring responsibilities. Offering greater job security (i.e. moving away from zero-hours contracts) and greater investment in training and development are also factors of ‘good work’. The TUC has called on the Mayor to use his position to champion these values, which it argues could be effected through greater employee representation on company boards. This borrows from the case study of Germany, where companies with over 500 employees are mandated by law to have 1/3 of representation on a supervisory board being made up of employees.

In terms of access, an essential part of work-life balance is a manageable commute. To that end, the WMCA has received funding as part of the HS2 project to improve public transport in the region and help ease traffic congestion. During peak times Birmingham is essentially gridlocked, and so investments such as the Midland Metro extension or the reopening of stations on the Camp Hill Line are a smart part of improving the quality of life in the city. The Mayor and leaders of the constituent councils of the WMCA should call in unison upon government to spend far more money on public transport in the region; £250 million for transport infrastructure in the West Midlands pales in comparison to the £17.6 billion budget for Crossrail in London. The bipartisan Environmental and Energy Study Institute in Washington, D. C. found that “there is a $4 economic return to a community for every $1 invested in public transportation“. Public transport investment doesn’t only allow people to travel further, faster and more reliably for work and leisure – it also makes financial sense.

The political case for more devolution

The centralisation of power and money in the UK has exacerbated problems with regional productivity and employment. Government cost-benefit analyses that determine infrastructure spending favour places that are already doing well, meaning that the lion’s share of investment has been on London and its hinterland in the South East. For instance, while the North of England receives £289 in transport spending per head, London receives £708; moreover, this gap has been growing over time. The result is that there has been underinvestment in regional infrastructure in the UK over a period of decades.

While central government may be aware of these problems, as we have seen, all too often local issues are not seen as a priority in Westminster. Only during general election campaigns do they seem to attract political attention and promises of investment. The result is a widespread sense of apathy and resentment towards politicians, of which Brexit can be seen as an incarnation. The British Psychological Society notes that major drivers of political apathy in the UK are a sense that politicians are dishonest, that the running of the country is in the hands of a few privileged elites, and the perception than the government is doing a bad job of solving problems people face.

It is of vital importance that these feelings are addressed and that people feel they have a greater ability to change politics. Devolving greater power to communities to shape their own future – to articulate what their own problems are, and find solutions adapted to local conditions – should be a priority. It must be part of a policy mix to encourage our society, as well as our economy, to be more inclusive and sustainable in the future.

This blog was written by Liam O’Farrell, Researcher at the University of Iceland and Research Associate of City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The opinions presented here belong to the author rather than the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.