Policymakers are once again focused on the potential of clusters to boost regional growth. However, as James Davies and Simon Collinson demonstrate, a cluster's contribution to growth can cross regional, national or even continental boundaries.

Policymakers, consultants and academics have focused on the potential of clusters to contribute to regional economic growth for a long time. Interest is cyclical, however, and currently, there is renewed interest from the UK government.

The aim is to stimulate agglomerations of similar, co-dependent or complementary firms which build a critical mass of economic activity in one place, attracting further investment and skills and creating positive multiplier effects for regional economies. It is an obvious target given both the UK’s current level of low growth and the disparities between regions.

Innovation Accelerators

Three innovation accelerators (Birmingham, Glasgow, Manchester) and various strengths in places-type funding emphasising local growth outcomes have been part of developing priority sectors in key regions away from London and the South-East. Some of these initiatives are sector-specific, focused on manufacturing, energy technologies, space, life sciences and healthcare, or the creative industries (as examined in the City-REDI Creative Clusters Project).

Are these efforts likely to be effective?

Traditionally, clusters were seen to emerge from a complex (often temporary) combination of ‘factor endowments’, which attract cumulative investments to create an agglomeration. These can include particular kinds of skills (or low-cost labour), capital assets, technologies and/or organisations like universities or government research labs, transport infrastructure, or local government subsidies and tax breaks. Together these provide a competitive advantage prompting firms to invest in a specific place. Other endowments, such as low-cost housing, good schools or local amenities have the same effect by enabling firms to attract high-level skills or scarce talent to that place. However, for some industry sectors, many of these drivers are increasingly irrelevant, as described below.

An established creative sector in the West Midlands, the videogame development cluster around the Warwickshire town of Leamington Spa, provides an example of some of these complexities. A key lesson for the government is the need to clearly define the parameters on which they are basing a cluster investment policy and to clearly map the contribution that the resulting clusters might offer to their host regions.

Silicon Spa, and Videogames in the West Midlands

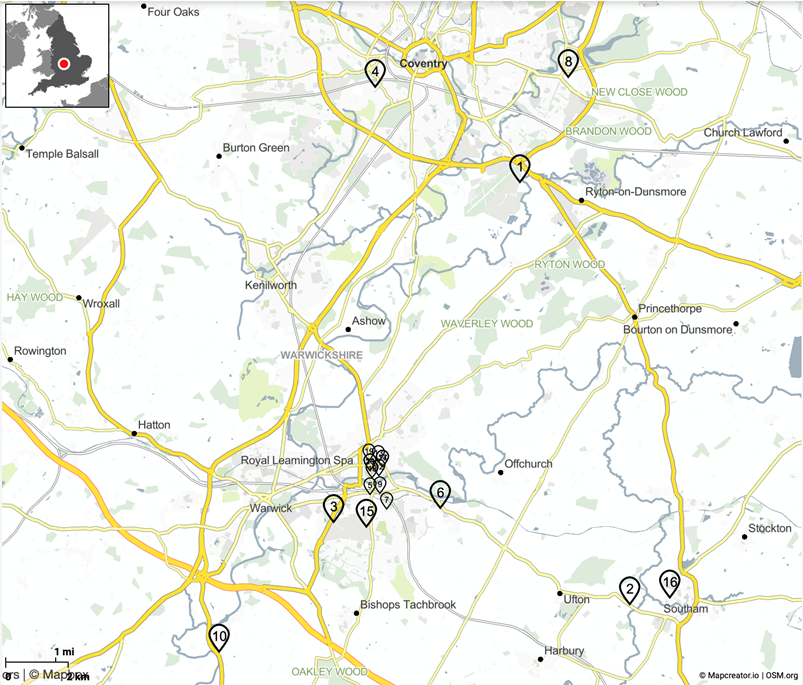

The West Midlands videogame cluster, known as Silicon Spa, comprises as many as 50 game development studios, based in and around the towns of Leamington Spa, Southam and Warwick. These studios include ‘Triple AAA’ PC and console developers like Playground Games, Codemasters and Ubisoft Leamington, mobile game development arms of large organisations such as SEGA Hardlight, as well as a slew of micro-business ‘indie developers’, often composed of just teams of a few people, or one developer working entirely solo. Impressive figures are thrown around in terms of the contribution of the cluster, with reports claiming that Silicon Spa comprises anything between 10% to 15% of the UK games industry in terms of employees, Leamington was identified by UKIE in 2020 as one of eight UK games hubs contributing more than £60m in GVA to their local economies, and ranking the town 3rd in Travel-to-work-area (TTWA), the highest contributor outside London and the South-East. Figure 1, below shows the locations of twenty of those companies, presenting a traditional image of what an industrial cluster looks like.

Figure 1: Studio Locations in and around Leamington Spa, Warwickshire

- 2p Games, Coventry

- Codemasters, Southam

- Fish in a Bottle, Leamington Spa

- Full Fat Games, Coventry

- SEGA Hardlight, Leamington Spa

- Kwalee, Leamington Spa

- Mad Fellows, Leamington Spa

- Midoki, Coventry

- Modern Dream, Leamington Spa

- Monster & Monster, Warwick

- Pixel Toys, Leamington Spa

- Playground Games, Leamington Spa

- Red Phantom Games, Leamington Spa

- UBISOFT Leamington, Leamington Spa

- Unit 2 Games, Leamington Spa

- Viewpoint Games, Southam

- Third Kind Games, Leamington Spa

- Super Spline Studios, Leamington Spa

- Well Played Games, Leamington Spa

- Soul Assembly, Leamington Spa

Patterns of Recruitment and Employment

The regional economic benefits of clusters depend largely on the generation of employment and therefore household income and local consumer spending. This comes directly from jobs in the firms that are part of the cluster, and indirectly from local companies (from cleaners to consultants) contracted by firms in the core cluster. In both cases, direct and indirect employment, across these tiered supply chains, needs to be local to create positive multiplier effects.

In the past, video game development was undertaken by teams based in the same physical studio environment. This has changed entirely. Remote working via online platforms had already changed the industry’s structure. This trend was accelerated by the double shocks of Britain’s exit from the EU and the Covid pandemic. Advances in digital infrastructure have facilitated entirely remote working for a variety of development roles, including coding and programmers as well as animators and artists. The extra challenges posed by hiring from within the EU post-Brexit have also encouraged studios to hire staff to work remotely.

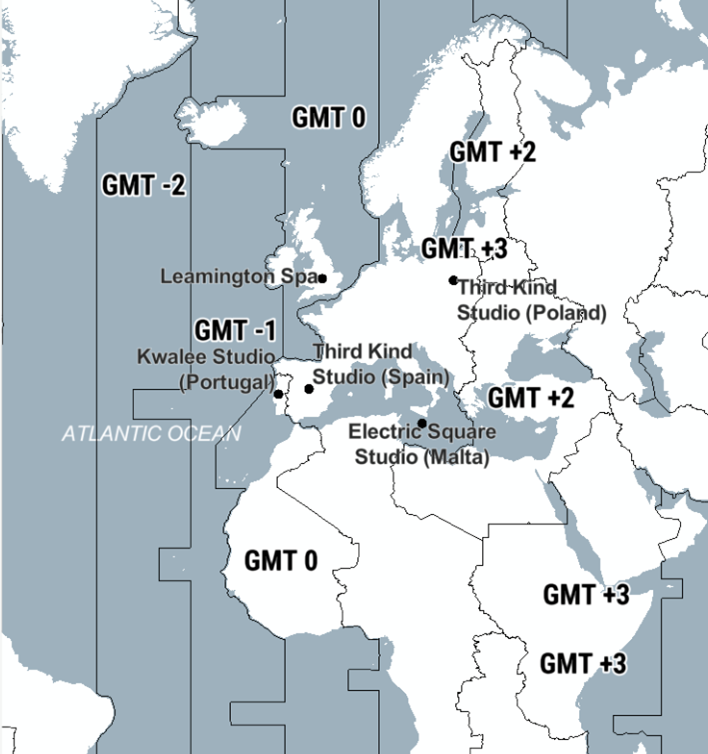

Job postings on gamesjobsdirect.com illustrate this, with independent animation studios such as Super Spline Studios advertising posts for employees based on any location within -3/+3 Hours of GMT, i.e. anywhere from Brazil to Saudi Arabia, with all of Europe and Africa, included. Other Leamington companies, such as mobile developer Kwalee list positions based in Portugal and Bangalore, and Third Kind Games boast a presence in Poland, as well as Spain. Electric Square, list its main UK office in Brighton, in addition to Leamington, as well as in Malta and Singapore. The potential reach of employment for the Leamington cluster is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Overseas Studio Locations & Locations for Remote Work (GMT -3/+3)

In an industry made up of 99% SMEs (which contribute an estimated £1.6bn + in GVA), there is also a huge amount of collaboration across projects too, with smaller studios offering a specific, segmented contribution to a much larger project. For example, Electric Square list their contribution to the development of the Triple AAA arcade racing game, Need for Speed: Unbound, developed by Guildford developer Criterion Games and published by American giant Electronic Arts. This also makes tracking the real economic impact of a cluster far more difficult to measure.

The Buck Stops There

So, employment patterns are not clustered, and neither is the consumer spending from employees in this sector. Many of the local multipliers associated traditionally with clusters do not therefore exist. There is also the question of ownership, and ultimately where ‘value appropriation’ takes place. Who (and where) benefits from the resulting revenues and profits? Large, Triple AAA releases are huge, complex projects, developed by multiple studios, with production budgets in the tens and even hundreds of millions, and estimated to be worth more than £800m in Gross Value Added (GVA) to the UK on their own. Two of the biggest studios in the Leamington area, Codemasters, and Playground Games, operate in this space.

Codemasters, a foundational pillar of the Leamington cluster, have existed in the area since the 1980s and cultivated a reputation in recent years as developers of top-quality racing console and PC titles, including the DiRT series and the official game of the Formula 1 World Championship. Similarly, Playground Games have built its reputation over the last decade on the phenomenally successful Forza Horizon racing series for Xbox consoles and PC. However, since June 2018, Playground Games have been owned by Microsoft, whose company HQ is based in Redmond in Washington, US. Despite operating independently for more than 30 years, in February of 2021, Californian publisher Electronic Arts paid more than $1bn to acquire Codemasters. Ubisoft Leamington, formerly known as Freestyle Games, are one of four UK studios owned by the Canadian publishing giant, whose founding offices are in Montréal, Quebec, and its current global HQ is based in Paris.

Figure 3: Locations of Parent Companies

- Leamington Spa, UK

- Sumo Digital (Parent Company of Lab42, Electric Square, Secret Mode, Super Spline Studios), Sheffield UK

- Tencent Holdings (Parent Company of Sumo Digital), Shenzhen, China

- Electronic Arts (Parent Company of Codemasters) & Meta Global HQ (Parent Company of Unit 2 Games) Silicon Valley, CA, USA

- Microsoft Global HQ (Parent Company of Playground Games) Redmond, WA, USA

- UBISOFT Montréal (Original Offices), Montréal, Quebec, Canada

- UBISOFT Global HQ (Parent Company of Ubisoft Leamington), Paris, France

- SEGA Global HQ (Parent Company of SEGA Hardlight), Tokyo, Japan.

This pattern is not confined to the Triple AAA console market either. SEGA Hardlight, a Leamington-based studio, develops for the mobile market, is subject to governance by SEGA Europe’s Brentford office, and is owned by the company headquartered in Tokyo, Japan. Unit 2 Games, a studio of just over fifty people based in Leamington, has been owned by Meta, the parent company of Facebook, since 2021. Finally, there is the case of Sumo. Since 2003, Sumo Digital has grown from a team of 13 people in Sheffield to 16 international studios. As well as its own branded UK operations in Leamington, Sheffield, Newcastle, Warrington and Nottingham, Sumo also sports its own studios in Pune and Bangalore in India, Czech Republic (Czechia), Poland and Canada. Other Silicon Spa studios, Atomhawk Advance and Lab42 are also under the Sumo Digital Umbrella. But it doesn’t stop there. Sumo Digital is ultimately owned by Chinese tech giant and multi-national Tencent Holdings.

What makes a Cluster a Cluster?

Is it a critical mass or agglomeration of similar companies, a certain level of contribution to employment and jobs to a cluster’s host region, or an economic impact that is difficult to unpack?

Is it a combination of all of the above?

The examples given here with reference to the Silicon Spa gaming cluster in the West Midlands are designed to illustrate the various ways in which clusters can be defined, and the vastly different geographic boundaries that emerge as a result. Based on the addresses of the studios themselves, the Leamington cluster appears localised within Coventry and Warwickshire. Considering the increasing utilisation of entirely remote working positions opens the cluster up to employing (without relocating) any talented individuals from across Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Factoring in collaborations and work smaller studios do on larger projects has a similar effect. Even independent studios now boast sister studios in Singapore, India and Malta. The ultimate owners of these studios make the picture truly global, whether they reside in North America (Meta, Microsoft, Ubisoft, Electronic Arts), China (Tencent) or Japan (SEGA).

Similar patterns are found elsewhere in the creative sector, and across other industries. High-End TV and Film shows clustering of production activity around London, Manchester, Glasgow and Cardiff, with an emerging cluster in Birmingham. For inward investment, however, large Streaming Video-on-Demand services like Netflix, Amazon and Disney, are viewing the whole of the UK as a ‘cluster’, based primarily on proximity to London as a hub for international travel. Netflix invests in South Wales because it is close to London relative to L.A. and there are strong tax incentives, relatively cheap skills and a pleasant work environment. Other territories, such as the Czech Republic (Czechia) are capable of offering many of the same benefits and attractions.

Lessons for Policy

Which places and people benefit more or less from different kinds of clusters? This is not simply a conceptual or methodological question. It relates closely to how an effective cluster policy can be delivered. As with any publicly funded investment designed to support local economic growth, we cannot assume that any region receiving £1 of public or private investment benefits by £1. The local value appropriation can be lower or higher, depending on the geographic scope of the related value chains and multiplier effects.

Depending on the criteria used to define a cluster, the value chains, spatial boundaries and apparent beneficiaries can vary significantly, crossing regional, national or even continental boundaries. This is particularly important for the current policy agenda because the geographic scope of their economic impacts can vary from substantial to irrelevant.

Any clusters policy should attempt to identify the likely employment multipliers, direct and indirect, that would result from new inward investments and a growing cluster of firms in a specific sub-sector and location. Alongside this, it is essential to trace the related value chains to identify who and where benefits.

This blog was written by Dr James Davies and Professor Simon Collinson, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.