Anne Green, David Waite and Richard Crisp discusses their new paper which compares the five leading agendas that have been positioned as alternative and progressive policy responses to urban economic change.

Decades of traditional growth-oriented economic policies have failed to stem widening social inequalities and rising environmental challenges. This has triggered growing interest amongst policymakers around alternative approaches to local economic development.

Perhaps the most well-known of these approaches is inclusive growth. It has gained traction amongst international and local organisations. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sees it as economic growth that creates opportunity for all segments of the population and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity – in monetary and non-monetary terms – across society. But this is only one of a number of different definitions. In a critique of inclusive growth, Neil Lee concludes that it is “conceptually fuzzy and operationally problematic”. As such it means different things to different people. Overall, however, Ruth Lupton and Ceri Hughes suggest that inclusive growth is a broad enough concept to provide a ‘jumping off point’ for local strategies and actions designed to ensure that prosperity and inclusion go hand-in-hand.

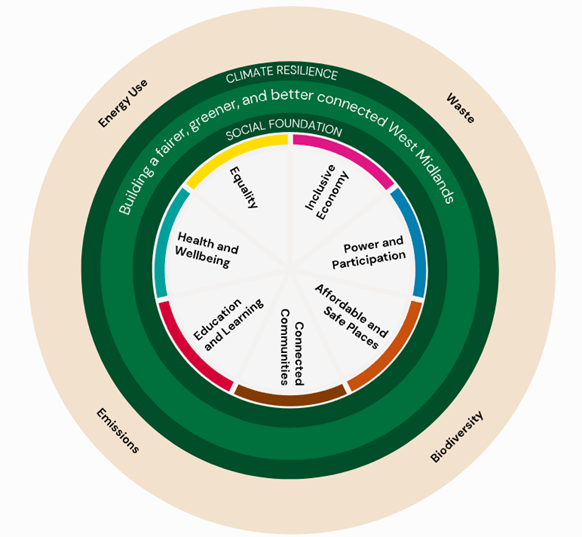

In the West Midlands, the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) has an Inclusive Growth Framework and an accompanying Inclusive Growth Toolkit. The WMCA defines inclusive growth as “a more deliberate and socially purposeful model of growth, measured not only by how fast or aggressive it is; but also, by how well it is created and shared across the whole population and place, and by the social and environmental outcomes it realises for our people”. The Framework comprises fundamentals derived from the Sustainable Development Goals and is structured according to Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model, as depicted in the Inclusive Growth Doughnut (as shown below from the WMCA website. Visit the WMCA website for a full description of the image).

This Inclusive Growth Doughnut is indicative of a ‘pick and mix’ approach to combining different elements from alternative economic development frameworks. Yet what do proponents of these alternative frameworks advocate?

The following table compares five alternative approaches – Inclusive Growth (IG), Wellbeing Economy (WE), Doughnut Economics (DE), Community wealth building (CWB) and Foundational Economy (FE). This fills an evidence gap as relatively little work has been undertaken to date to compare and contrast these alternative approaches.

An overview of the five ‘alternative’ approaches

| Inclusive Growth (IG) | Wellbeing Economy (WE)

|

Doughnut Economics (DE) | Community Wealth Building (CWB) | Foundational Economy (FE) | |

| Emergence | Late 2000s, increasingly gaining traction from c. 2015 | Wellbeing economics since late 1980s, gathering pace from late 2000s | Pioneered by Kate Raworth 2012, expanded in her 2017 book | Mid-late 2000s in UK and US, with increasing traction since c. 2015 | From 2013 (Manifesto for the Foundational Economy), increasing traction since COVID-19 pandemic |

| Leading Proponents | OECD

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Centre for Progressive Policy (UK)

Brookings Institution (US) |

Wellbeing Economy Alliance (global)

New Economics Foundation (UK)

Carnegie UK |

Kate Raworth and Doughnut Economics Action Lab (UK) | CLES (UK)

Democracy Collaborative (US) |

Foundational Economy Collective of researchers (a mainly European group)

|

| Vision | An economic system which enables the greatest number and range of people to participate in economic activity and to benefit from economic growth

|

Economies which promote ecological sustainability, intergenerational equity, wellbeing and happiness, and a fair distribution and efficient use of resources | An ecologically safe and socially just space (the Doughnut) in which humanity can thrive | Local economies are organised so that wealth is broadly held and generative of income, opportunity, dignity and well-being for local people (wealth for all)

|

Society is strengthened by focus and investment on the infrastructures that make civilised everyday life possible

|

| Urban Examples | West Midlands (UK)

New York, Paris, Seoul, Athens |

North of Tyne (UK), Santa Monica (US) | Amsterdam,

Brussels, Melbourne |

Preston (UK),

North Ayrshire (UK), Barcelona, Cleveland (US) |

Barcelona, Enfield (UK), Wales |

Source: Authors’ research (Crisp et al., 2023)

There are some differences in terms of the visions set out, the mechanisms for change articulated, and the geographies that the approaches respond to. In terms of visions, WE and DE are arguably most pronounced as they hinge on a vision of the “good life”. With regard to mechanisms for change, there is a common concern for democratic participation. However, there are marked differences in terms of prescriptiveness (with CWB being the most prescriptive). With respect to geographies, strikingly, there is rarely an explicit articulation of the geographic disparities to be addressed (aside from CWB), despite the mobilisation of these approaches by local authority actors – albeit in Birmingham the Birmingham Anchor Network has a ‘community wealth builder in residence’. Here work is being done to open up entry-level vacancies to those in greatest need and to use procurement opportunities to increase their contribution to the Birmingham economy.

As part of a Royal Society of Edinburgh Research Workshop series with colleagues at the University of Glasgow and Sheffield Hallam University, as well as at the University of Birmingham, we have been exploring how alternative economic approaches are being operationalised in local policymaking contexts.

A workshop in Birmingham in July 2023 surfaced considerable interest in learning about alternative approaches and their implementation but concluded that while crises drive policymakers to search for alternative approaches, there is not yet a clear movement towards them. Rather the reality is one of patchwork funding and accountabilities, with concurrent pressures that both demand and stifle innovation. Hence, while the context for policy implementation is not ideal, it is imperative to ‘get on and act’ at the local level regardless.

It is also important to identify what success looks like and how this can be measured. This requires integration across geographical scales and data sources so as to work across policy silos and measure what is happening at the local level – and how this links to larger trends and ultimately bigger goals. Here it is notable that Ladywood, a neighbourhood in Birmingham, has a Neighbourhood Doughnut Portrait, which is a product of community-based work. Going forward, this suggests that local and regional authorities could work more closely with community groups in exploring alternative economic development approaches, what they might mean in practice and how they might be implemented.

Reference and credit for full paper referred to in this blog – Crisp, R., Waite, D., Green, A., Hughes, C., Lupton, R., MacKinnon, D. and Pike, A. (2023) ‘Beyond GDP’ in cities: assessing alternative approaches to urban economic development. Urban Studies, OnlineFirst. Copyright © 2023 (Crisp, R., Waite, D., Green, A., Hughes, C., Lupton, R., MacKinnon, D. and Pike, A). doi.org/10.1177/00420980231187884

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.