Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates is a bi-annual publication which will get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WM REDI staff and guest contributors will discuss some of the key topics when trying to understand the long-term economic impacts of the pandemic.

Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates is a bi-annual publication which will get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WM REDI staff and guest contributors will discuss some of the key topics when trying to understand the long-term economic impacts of the pandemic.

In this article, Dr Magda Cepeda Zorrilla looks at the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on mobility in the West Midlands and provides a series of recommendations on how transport authorities can approach this “new normality”. Dr Cepeda Zorrilla outlines a recovery plan that covers public transport, walking and cycling in the short, medium and long term. As well as explaining how this plan can help to address new problems that COVID-19 has created, and issues that already existed such as traffic congestion, air pollution and social inequalities in the region.

There are many factors that research has highlighted as influential in the development of COVID-19. However, the focus of this article is on two main factors that are relevant to the West Midlands which affect the spread of the virus as well as the severity of its symptoms and exacerbation of health conditions that might lead to a higher rate of mortality. These influential factors are air pollutants (Cole, M. et al. 2020; Sasidharan, M. et al. 2020; Xiao, W. et al. 2020; Wu, C.et al. 2020) and the contact rate (Ferguson et al. 2020).

In 2017 in the West Midlands, the measurement of the air pollutants showed levels above the guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO) (DEFRA and PHE, 2017) which placed the region in a risky position for exposure to coronavirus. With respect to contact rates, Birmingham is the UK’s second-largest city. The region has also an ageing population, which are more vulnerable to suffer from the coronavirus and “the proportion of people aged over 60 is projected to increase from 20.3% in 2014 to 23.8% by 2039” (TfWM, 2016). This is relevant because research has shown that “excess deaths as a proportion of usual deaths rise with age” (Tallack, C. et al., 2020).

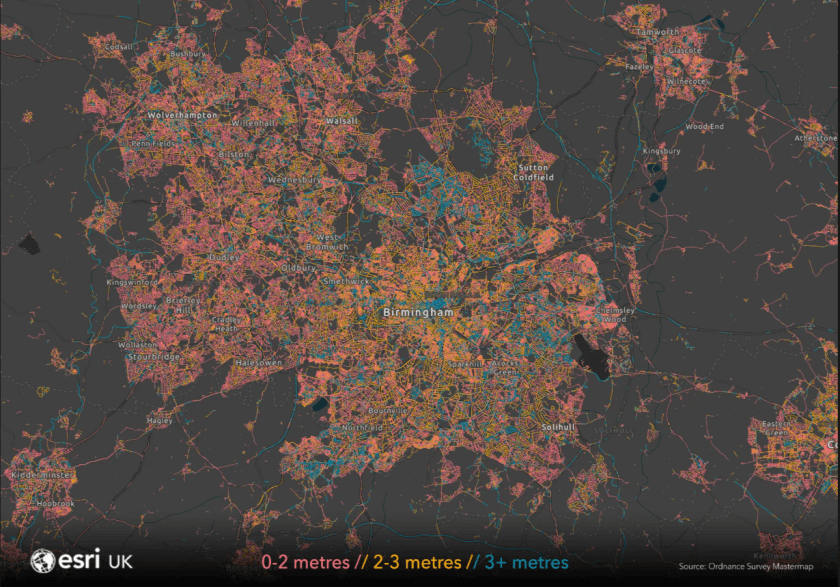

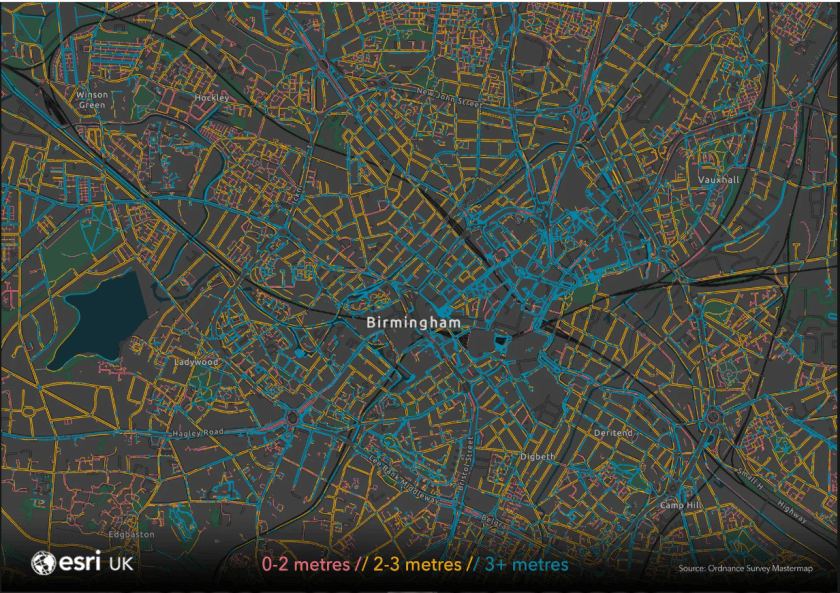

To reduce the contact rate, measures such as social distancing should be maintained, however, some areas in the region would find it difficult to do this. ESRI, a company that specialises in mapping software, has produced maps of every footpath width in the UK. The analysis found that “only 30% of Great Britain’s footpaths are at least 3 metres wide, 36% are between 2-3 metres and 34% are less than 2 metres wide” (ESRI, 2020). In the West Midlands, maps of Birmingham, which has a high population density, show that the city does not have the conditions to provide the minimum distance of separation for pedestrians.

Therefore, it is critical for the region to carry out particular changes and interventions in the urban environment and to transport services to be able to respond to the challenges faced by COVID-19.

Below there are a series of recommendations proposed to face these challenges. The recommendations are divided into four areas

- Service adjustments

- Changes in infrastructure and mobility alternatives

- Behavioural changes

- The production of further evidence

Services adjustment

In order to keep the transmission of the coronavirus as low as possible, it is essential to minimise the risk of contagion in public transport. Therefore, special attention needs to be given to changes such as frequent sanitising, back-door boarding, cashless operations and occupancy limit to allow for physical distancing.

- In the short term, in response to COVID-19, the WHO (2020) have suggested maintaining a cleaning routine that should be undertaken using hospital-grade cleaning and disinfecting agents for frequently touched areas. In the cases of public transport poles and areas to be touched should be wipe down frequently (potentially at the end of the route) but also spraying disinfecting mist for the rest of surfaces. Additionally, staff undertaking the job should have adequate materials to be safe such as face masks and gloves.

- Back-door boarding on buses has also been advised by experts (UITP, 2020). However, this means also that services adjustments are required in the West Midlands in the short term. For instance, the use of smart cards for cashless operation for all public transport and installing machines in the back-door could be used to pay the fee while boarding the transport. Even if the drivers have a protective door, installation of the machines in both doors can be used, and this will help to distribute the people boarding the buses, allowing greater distances between each passenger. This measure can help in the medium and long term to reduce waiting delays at bus stops.

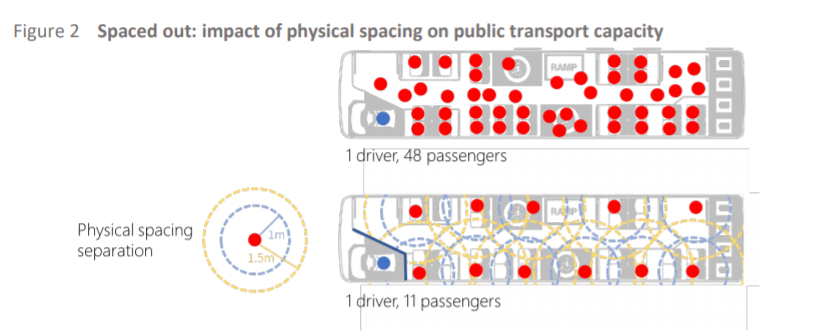

- Increase the frequency of the bus services to allow for social distancing during the trips and to avoid long waiting queues. An example of the difference in capacity maintaining social distancing is shown in the image below.

Spaced out: impact of physical spacing on public transport capacity. Source – ITF. 2020 To help with this, some operators have already developed a tool to inform travellers which bus is less busy. This is linked to repurposing streets in the short term and infrastructure investment in the medium term. For instance, providing exclusive corridors to the additional fleet of buses can help to reduce the risk of buses caught in congestion at peak times, which is an old problem in Birmingham according to research (Forth, T. 2019) and increases the exposure risk to coronavirus for the passengers.

Changes in infrastructure and mobility alternatives

According to WMCA (2019) pre-COVID-19, approximately 41% of journeys in the region made by car were under 2 miles, therefore before the coronavirus outbreak, there was potential for cycling in the region. But in order to increase bicycle use, different measures and combined strategies are necessary.

- Wider public sharing programs for bicycles, e-bikes and e-scooters are essential in order to distribute the demand for public transport and to avoid a spike in the use of a car to commute. The West Midlands is already planning trials for the e-scooters share system, but other options such as e-bikes and a bicycle share systems could be also encouraged in the medium term.

- Infrastructure and shared programs for alternative mobility are equally important. Research shows the positive effect of combining cycling infrastructure and bike-sharing systems in increasing the use of the bicycle (Felix, R. et al. 2020).

- Although there are several sociodemographic, attitudinal, and transport characteristics that influence bicycle use (Fyhri, A. 2017), cycle infrastructure is essential. Previous research (Hull, A. and O’Holleran, C., 2014) stated the importance of prioritising cyclists and to provide a safe, comfortable and attractive network to make cycling more attractive than private vehicles. The authors suggested that government fiscal policy can help to reinforce this through car taxation and tangible restrictions associated with owning a car, however, for this a strong leadership from the government will be necessary.

- An approach that can be used to implement short term bottom-up interventions is using what is known as “Tactical Urbanism” (TU). TU was defined by the Tactical Urbanism Toolbox in the Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action, Long-Term Change (Lydon, M et al. 2012) and is characterised by developing measures in a phased approach, based on local ideas, involving short-term commitment and low risk (potential with a high reward), and the development of social capital and collaborative partnerships. In the case of the West Midlands, this could translate in the mobilisation of existing resources such as traffic cones and the construction of temporary emergency cycle lanes. It can be used to help to repurpose general traffic lanes and streets. The same approach can be used as an alternative to widening the footpaths to help to maintain space between people, whilst other changes in infrastructure for widening the footpaths are carried out in the medium term. Successful examples of this approach can be found for instance in Spain (Besson, R., 2016), USA (Lydon, M et al. 2012) and New Zealand (Kingham, S. et.al 2020).

Behavioural changes

A recent survey carried out by a Consultancy found that in the UK, people fear the risk of the spread of the COVID-19 on public transport and therefore try to make less public transport journeys. This may potentially increase of the use of private motor vehicles to commute, which in turns will negatively affect the air quality (already poor in the region), cause traffic congestion and consequently delays for public transport and will ultimately affect climate commitments of the UK Government. Therefore, measures focusing on addressing peoples’ fears and questions as well as dealing with negative perception and attitudes is something that is essential in the short and medium-term.

- Campaigns communicating the health and safety measures taken by the transport operators could be very important to influence peoples’ perception positively.

- The UK Government (UK. 2020) had already suggested that if possible travel at off-peak times, however, it is essential that government works closely with trade union reps to provide support at negotiating with employers necessary changes in travel behaviour when travelling to work.

Research and further evidence

Planning for urban mobility, especially post COVID-19, requires analysis, creation of models and simulation scenarios. Therefore, it is very important to strengthen collaboration between academia and the public sector in order to produce empirical evidence and forecasting tools to inform policymakers and practitioners.

- A recent study carried out, in London (Sasidharan, M. et. al. 2020) investigated how measuring the levels of air pollutants in the city could support transport planners fighting COVID-19. The authors concluded that air pollution could be used as an indicator of vulnerable spots in the city. By identifying these spots, policymakers can decide quickly where to reduce or suspend public transport operations, considering the link between poor air quality and COVID-19 transmission. A similar study West Midlands could be very helpful for the reasons expressed previously.

- Further research on behavioural models using theoretical frameworks can be helpful to understand the link between peoples’ attitudes and behaviour and to be able to predict their behaviour. Investigation of underlying factors influencing peoples’ modal choice can help to produce targeted policy measures and interventions that can be more successful than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Summary

In summary, the West Midlands is a region already facing many mobility challenges and COVID-19 is adding to these. However, by addressing the present challenges the region can also tackle the old issues. In order to do this, in the “new normality”, it is important to have strong leadership from the authorities but also needs collaboration between different groups such as civil organisations and academia in order to develop measures and interventions that work in the short, medium and long term.

This blog was written by Dr Magda Cepeda Zorrilla, City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham