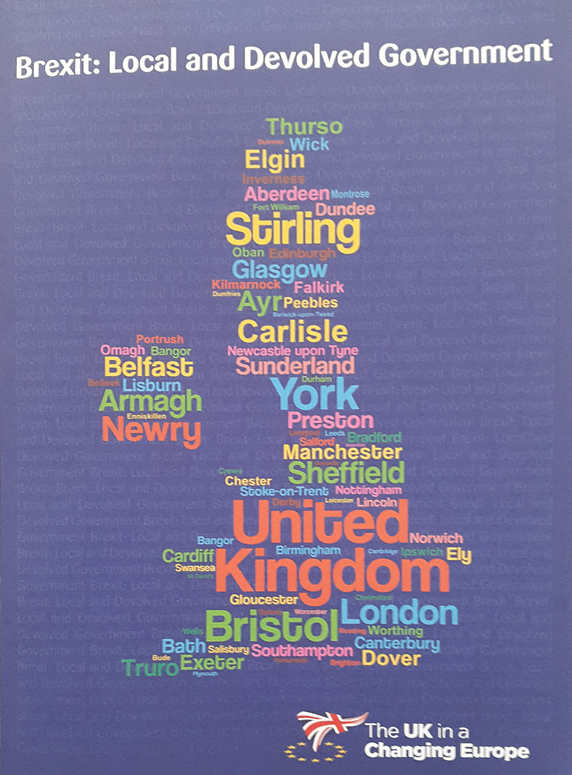

This week the new report Brexit: Local and Devolved Government has been launched. The report considers not only what happened in the EU referendum itself but also the consequences of Brexit at the sub-national level. The report was launched to coincide with The UK in a Changing Europe’s conference Brexit: local and devolved government, which took place yesterday at Royal Institute of British Architects in London.

The contribution by Will Jennings, Gerry Stoker and Ian Warren focuses on the regional differences revealed by the Brexit vote. In particular, the authors argue that the fact that many major cities voted heavily for Remain while rural areas tended to vote for Leave may be a clear reflection of a difference of identities and a cultural backlash but also of long-term forces of socio-economic change that have caused a polarisation in the attitudes, experiences and expectations for a post-Brexit Britain. The authors argue that Brexit has accentuated political divisions among places. Their analysis shows that places that have experienced the greatest decline in recent decades (in terms of population growth, economic activity or outflow of younger and educated workers) tended to vote Leave.

Andrew Carter’s contribution to the report starts to imagine how Britain would have been if the Remain vote would have been the outcome of the referendum. He reflects on the economic challenges that the coming decades will bring for UK cities regardless of Britain’s decision to leave the EU and the disparities of these challenges among the UK geography. Issues related to automation and globalisation are likely to hit differently different parts of the UK. His contribution also highlights that under either trade scenario, the economically vibrant British cities are set to see a fall in economic output as a result of leaving the EU. However, the most affected cities are in a better position to react to the predicted shocks ahead due their diverse industrial structure and strong economy.

The contribution by Chloe Billing, Philip McCann and myself stresses again the fact that UK regions which voted Leave tend to be more dependent on European markets for their prosperity than those regions which voted Remain. In contrast, the wealthier Remain-voting regions of the UK, in and around London and in Scotland are less exposed to wider Brexit trade-related risks in comparison with the economically weaker Leave voting regions. Moreover, many Leave voting regions have also been major beneficiaries of EU Cohesion Policy and these funding streams will also be lost post-Brexit. The results of these adverse Brexit effects will bring greater inter-regional imbalances. Our contribution argues that the challenge will be how to prepare to respond to the shocks, and again on this there are clear regional differences in the sub-national landscape. Many regional governance stakeholders have been proactive. In particular the devolved administrations and bigger cities have been more pro-active than many of the smaller localities. Examples can be found in the “Europe and External Relations Committee” set by the Scottish government, the Welsh Government Economic Action Plan, the monthly Brexit briefing papers by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority and the London Mayor’s commissioning of an Independent Economic Brexit Analysis., all of which reflect the need for places to prepare against the shocks set by Brexit. We end up our contribution with some observations about how things will develop. The re-domestication of regional policy will almost certainly mean the re-politicisation of it, making long-term commitments all the more difficult. But also the movement towards industrial policy should consider the place-based issues as a key element.

The report offers many more contributions regarding the devolved areas. Sir John Curtice discusses the politics of Brexit in Scotland. His contribution illustrates the nature of the vote of the EU referendum in Scotland and its relationship with the previous Independence referendum, along with the consequences of the snap general election results. Brexit has exposed a fissure in the nationalist movement, which turned-out to be more of a problem than an opportunity. Meanwhile, Michael Keating’s contribution about Brexit and Scotland is developed around the potential constitutional changes and the division of powers that might occur because of Brexit. The proposal that powers currently shared between Scotland and Brussels should now revert to Westminster has now become a major battleground. Similarly, Roger Awan-Scully contributes to the debate with his political views on Brexit, Wales and Devolution aspects of the Withdrawal Bill. Again, the Welsh Government has found itself battling what it sees as potential power grab by Westminster.

Katy Hayward contributes to the report by looking at the case of Northern Ireland. Her contribution stresses the uncertain times after the referendum in June 2016 and the impacts of the vote on the political culture of the province. The subsequent retreat to the familiar territory of “unionism” and “nationalism” is as unsurprising as it is regressive, and poses problems for ongoing and future governance. The problem of the border is still very real and challenges the foundations of the 1998 Agreement.

Dan Wincott contributes to the report with a discussion of Brexit and English identity. A clear majority of people who identify as English rather than British voted Leave whereas those who identify as British rather than English voted Remain, while by a narrow margin those with equal identifies voted Remain. Voters with very strong English identities are also willing to tolerate the break-up of the Union and the destabilising of the Northern Ireland peace process in order to secure Brexit. The blurred relationships between English and British identities may also have implications for devolution within England.

Finally, Noah Carl and Anthony Heath finish the report by analysing the sovereignty principle as an argument for supporting the vote to Leave in the UK referendum. The authors comment on where the power could be repatriated after Brexit, such as to the devolved administrations and the regions or cities. Analyses of the where pro-Remain and pro-Leave voters think that decision-making power over different areas should lie suggests that there is still only very limited support for city or regional power within England.

As a whole this collection offers some profound insights on the complexity of the UK’s sub-national arena in the post-Brexit context but presents them in a concise and easily digestible format accessible to a very wide audience. Anand Menon and his team at UK in a Changing Europe have done us all a real service.

You can access to the report here: Brexit: local and devolved government.

This blog was written by Professor Raquel Ortega-Argiles, Chair, Regional Economic Development, City-REDI, University of Birmingham

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.