A Brief History

On 14 April 2020, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) published a scenario in which the UK would see a real GDP fall of 35% in Q2 2020, followed by a quick bounce back. Under this same scenario, unemployment rises by more than 2 million to a total of 3.4 million (10%) in Q2 2020 but then declines more slowly than GDP recovers (OBR, 2020).

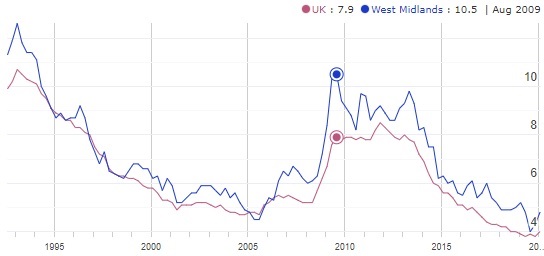

Previous recessions have seen marked increases in unemployment (as shown in Figure 1). During the Great Recession, the rise in unemployment was less dramatic than many commentators expected; but there was an unprecedented weakness in productivity and stagnation in real incomes (Hughes et al., 2020). In the 1980s the annual unemployment rate averaged 11.2% between 1982 and 1987, while from 2008 to 2013 it averaged 7.5% (Bell and Blanchflower, 2020). In the West Midlands, the unemployment rate remains higher than the national average, and in the Great Recession, regional unemployment peaked before the UK (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Unemployment rate in the UK, 1971-2019

Figure 2: Unemployment rate in the UK and the West Midlands, 1992-2020

The data in Figures 1 and 2 suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has hit the UK at a time when the labour market is tight. Clearly at the end of 2019 unemployment rates were well below those recorded in the Great Recession – but the trend of declining unemployment had begun to reverse. Indeed, Bell and Blanchflower (2020) dispute that the UK had a tight labour market at the onset of the pandemic, highlighting that the underemployment rate (measured as the number of part-time workers who say they want full-time jobs) was still above pre-recession levels in 2019.

The Current Situation

Although there is some delay in data becoming available, to date the level of claims and the speed of their increase is unprecedented, with almost one million new claims for Universal Credit (UC) in the last fortnight of March 2020. Analyses by the Learning and Work Institute on the labour market impacts and challenges of the coronavirus show that this was 7.3 times higher than the same period a year earlier. During the peak of the last recession, claims for Jobseeker’s Allowance the peak in new claims was just 1.8 times higher than the previous year (Evans and Dromey, 2020).

Policies such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme should both limit the scale of unemployment increases and the extent to which joblessness persists (Hughes et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it is clear that labour market policy will need to address higher levels of unemployment over a longer period than has been the case in recent years. Moreover, as in previous recessions, young people are expected to find themselves particularly hard hit, with analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies showing that employees aged under 25 years were about two and a half times as likely to work in a sector that is now shut down as other employees (Joyce and Xu, 2020).

So what does this increase in unemployment associated with the COVID-19 pandemic mean for labour market policy?

In their analyses of the labour market impacts of COVID-19 the Institute for Employment Studies (Wilson et al., 2020) and the Learning and Work Institute (Evans and Dromey, 2020) each identified five priorities for action, while analyses by the Resolution Foundation (Hughes et al., 2020) point in a similar direction. Combined they make six priorities (in no particular order of importance) – as presented in Box 1:

Box 1: Labour market policy priorities

| 1. Investment in new active labour market programmes for those out of work – including: – rapid employment of the newly unemployed – preventing long-term unemployment – through investment in employment support – specialist support for the long-term unemployed/disadvantaged2. Refocusing skills and training to support recovery – including through: – pre-employment training – advice and guidance – matching those out of work to short- and long-term jobs growth areas – local partnership working3. An integrated coherent offer to support young people – by bringing together youth employment, training, skills and welfare support in order to avoid a ‘pandemic generation’ of young people scarred with poorer education, earnings and skills prospects resulting from sustained periods of unemployment (as has been evident in previous recessions [Clarke, 2019]), especially given that evidence suggests that in the light of changes in the youth labour market and at times of uncertainty, employers take fewer risks on young people with less experience than their older peers..4. Preparation for an orderly withdrawal from the Job Retention Scheme5. A partnership-based ‘Back to Work’ campaign – using existing local partnership arrangements and reflecting the fact that local government and LEPs need to play an important role in recovery, including in ensuring that policies are joined up at local level.6. Planning for the future – to achieve high quality more productive employment with improved opportunity and security (as highlighted in the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices). |

Source: based on Wilson et al. (2020) and Evans and Dromey (2020)

Already young people have been designated a top priority in the West Midlands given the higher than average share of young people in the population. There are key questions for policymakers regarding:

- How can work-based learning help minimise the impact of the crisis on the labour market outcomes of young people?

- How well equipped is the skills and learning system to respond to the crisis?

- What could be done to ensure the crisis does not exacerbate inequalities in opportunity?

Work on an evidence review to support the development of the Employment Support Framework within the West Midlands Combined Authority can inform future policies to help people enter and progress in work. Examples of relevant learning with regard to young people include:

- The importance of young person led outreach and engagement to reach those individuals who are ‘hidden’ and of holistic and long-term support to de-risk transitions into employment – as shown by Talent Match.

- Close collaboration between providers of employability support and other types of support matters – as shown by the experience of the effectiveness of the integrated employment and skills MyGo service for young people in Ipswich shows (Bennett et al., 2018).

- A role for job guarantees delivered via wage subsidies – building on learning from the Future Jobs Fund, which facilitated funded, six-month paid jobs for young adults in the aftermath of the financial crisis, with sizable positive effects (Fishwick et al, 2011; Department for Work and Pensions, 2012).

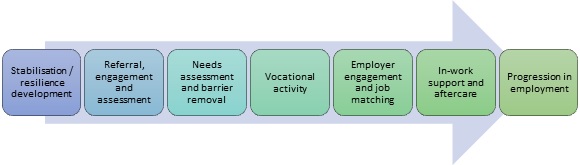

The evidence review is organised around seven stages on a continuum from those who are disadvantaged and some way from employment through to progression in employment (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Journey into and within employment

Cross-cutting themes and principles identified in the Evidence Review are pertinent for guiding employment support policy interventions in the context of building resilience and recovery in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Box 2). So there is an evidence base to draw upon – albeit there are significant challenges in getting the different elements aligned.

Box 2: Cross-cutting themes and principles for guiding employment support policy

| For individuals | Programme design/ operation | Key role of employers |

| Value of personalised support | Co-design can yield better policy while improving the well-being and employability of those involved | Links with employers are fundamental – need to understand their requirements and practices |

| A role for peer support and mentoring | The quality of key worker support matters | Employer engagement can take the form of an ‘agency’ approach or an ‘individual approach’ |

| Holistic intensive support is needed for the most disadvantaged | Benefits from the co-ordination of local provision and from local partnership working | Brokerage between employers, HR managers, education and training providers and job seekers is important |

| Long-term support is beneficial – especially for the most disadvantaged | Benefits of a ‘dual customer approach’ support the objectives of employers and (prospective) employees | Employers (and beneficiaries) can benefit from active involvement and engagement with employability programmes |

| Training and skills acquisition facilitates employment entry and in-work progression | ||

| Work placements can be helpful |

Source: based on Green and Taylor (2019)

References

Bell D N F and Blanchflower D G (2020) ‘US and UK labour markets before and during the COVID-19 crash’, National Institute Economic Review 252, R52-R69.

Bennett L, Bivand P, Ray K, Vaid L and Wilson T. (2018) MyGo Evaluation: Final Report. Learning and Work Institute, Leicester.

Clarke S (2019) Growing Pains: The impact of leaving education during a recession on earnings and employment, Resolution Foundation, London.

Department for Work and Pensions (2012) Impacts and costs and benefits of the Future Jobs Fund.

Evans S and Dromey J (2020) Coronavirus and the Labour Market: Impacts and Challenges, Learning and Work Institute, Leicester.

Fishwick T, Lane P and Gardiner L (2011) Future Jobs Fund: an independent evaluation, Inclusion, London.

Green A and Taylor A (2019) Review of the evidence on ‘What Works’ to support the development of the Employment Support Framework within the West Midlands Combined Authority, West Midlands Combined Authority.

Hughes R, Leslie J, McCurdy C, Pacitti C, Smith J and Tomlinson D (2020) Doing more of what it takes: Next steps in the economic response to coronavirus, Resolution Foundation, London.

Joyce R and Xu X (2020) ‘Sector shutdowns during the coronavirus crisis: which workers are most exposed? IFS Briefing Note BN278, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

Office for Budget Responsibility (2020) Commentary on the OBR reference scenario

Wilson T, Cockett J, Papoutsaki D and Takala H (2020) Getting Back to Work: Dealing with the labour market impacts of the Covid-19 recession, Institute for Employment Studies, Brighton.

Youth Futures Foundation and Impetus (2020) Young, vulnerable, and increasing – why we need to start worrying more about youth unemployment, Youth Futures Foundation and Impetus, London.

City-REDI / WM REDI have developed a resource page with all of our analysis of the impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on the West Midlands and the UK. It includes previous editions of the West Midlands Weekly Economic Monitor, blogs and research on the economic and social impact of COVID-19. You can view that here.

This blog was written by Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.