Anne Green examines rates of economic inactivity in the West Midlands. Who is inactive and why? This article was written for the Birmingham Economic Review 2023. The review is produced by City-REDI / WMREDI, the University of Birmingham and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce. It is an in-depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and a high-quality resource for informing research, policy and investment decisions.

In the context of concerns about labour and skill shortages, policymakers have increasingly focused attention on the economically inactive, defined as people not in employment who have not been seeking work within the last four weeks and/or are unable to start work within the next two weeks.

Economic inactivity in the UK

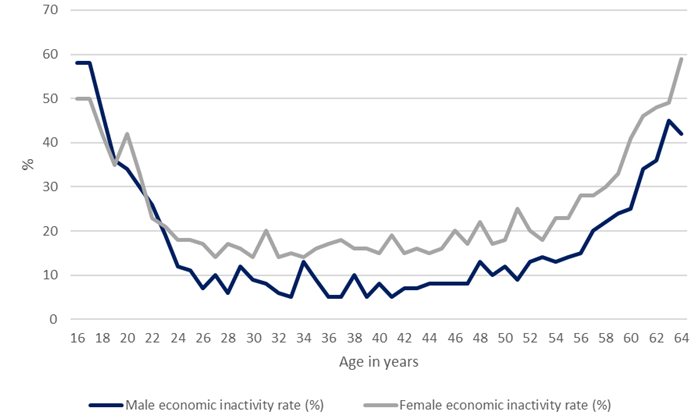

According to the 2022 Annual Population Survey, just over 9 million people of conventional working age (16-64 years) in the UK were economically inactive. People at either end of this age distribution are most likely to be economically inactive (as shown in the figure below).

Economic inactivity rate (%) by age and sex for people aged 16-64 years, UK, July to September 2022

Economic inactivity in the West Midlands

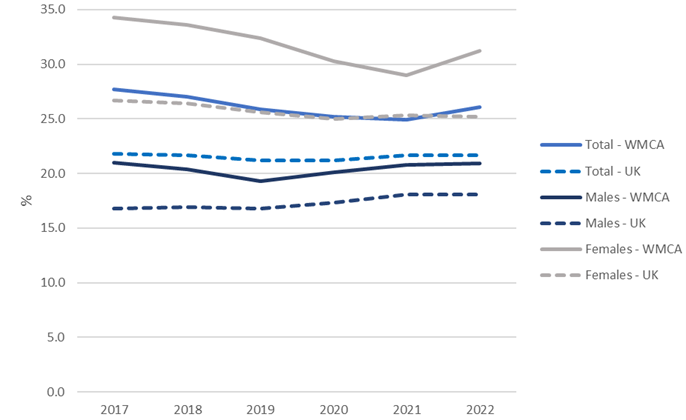

In the West Midlands metropolitan area, nearly 485 thousand people aged 16-64 were economically inactive in 2022. Females accounted for three in five of the economically inactive. The figure below shows the trend in the economic inactivity rate by sex for people aged 16-64 years over the period from 2017 to 2022 in the West Midlands metropolitan area in comparison with the UK.

In the West Midlands metropolitan area, the economic inactivity rate for both males and females was slightly lower in 2022 than in 2017 but slightly higher than in 2020. Inactivity rates were higher in the West Midlands metropolitan area than in the UK, at 26.1% overall (UK: 21.7%), 20.9% for males (UK:18.1%) and 31.2% for females (UK: 25.2%).

The trend in economic inactivity rate (%) by sex for people aged 16-64 years, 2017-2022, in the West Midlands metropolitan area and the UK

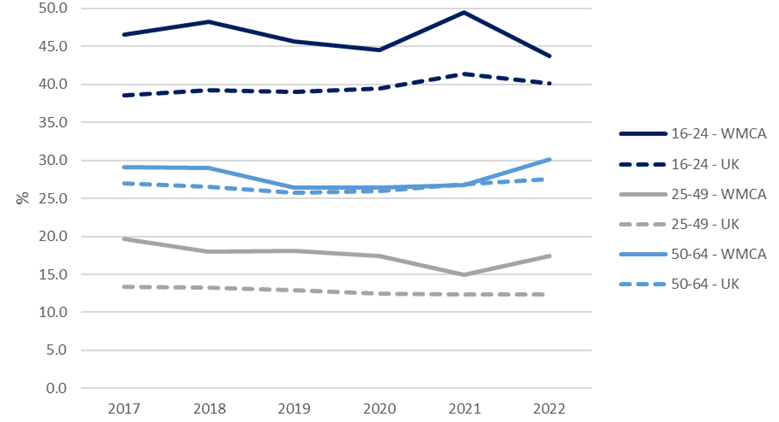

The figure below shows the trend in the economic inactivity rate by broad age group over the period from 2017 to 2022 in the West Midlands metropolitan area in comparison with the UK. In the 16-24 years and 25-49 years age groups economic inactivity rates have remained stubbornly higher in the West Midlands metropolitan area than in the UK throughout the period. The local-national difference is less marked in the 50-64 years age group.

The trend in economic inactivity rate (%) by broad age group, 2017-2022, in the West Midlands metropolitan area and the UK

Economic inactivity in the West Midlands by ethnic group and sex

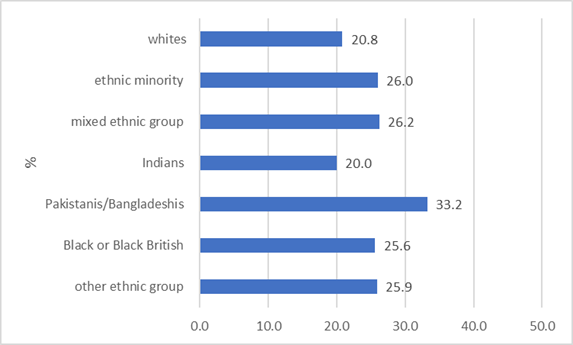

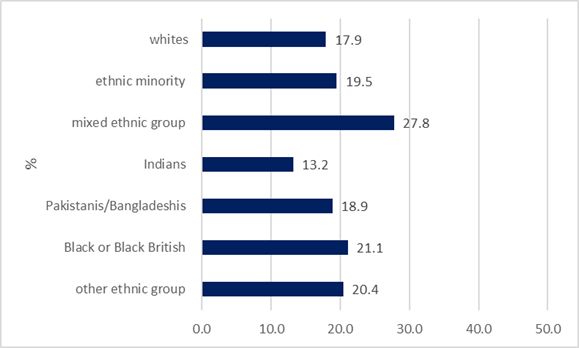

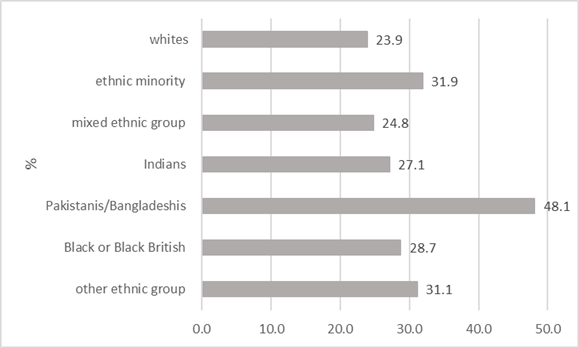

Given the ethnic profile of the West Midlands metropolitan area, it is also instructive to examine economic inactivity by ethnic group and sex. The three figures below show that in 2022 the economic inactivity rate for ethnic minority groups overall was higher than for white residents but there are marked differences in economic inactivity rates between ethnic minority groups.

Economic inactivity is highest for the Pakistanis/Bangladeshis group, with one in three economically inactive. However, amongst females, nearly half are economically inactive compared with only 18% of males. For females, all ethnic minority groups identified display higher economic activity rates than white residents aged 16-64 years. Amongst males aged 16-64 years Indians display the lowest economic inactivity rate (13.2%). However, Indians are the only group exhibiting a lower economic inactivity rate than white residents amongst males.

Inactivity rate (%) by ethnic group and sex, 2022, in the West Midlands metropolitan area

Source: Annual Population Survey (via Nomis)

A decline in people wanting to work

While the economically inactive are seen as a potential source of labour supply to address labour and skills shortages it should be noted that only a minority – 15.9% of the economically inactive aged 16-64 years in the West Midlands metropolitan area (UK: 17.9%) – wanted to work in 2022. The proportions wanting a job are fairly similar for males and females. In the West Midlands metropolitan area, as in the UK, the proportion of economically inactive people wanting a job has declined since 2020 (i.e., the height of the Covid-19 pandemic).

This represents a challenge for the economy of Birmingham and the West Midlands. Much of the attention during and since the Covid-19 pandemic when vacancies surged has been focused on the over-50s. In part this is due to the fact that the pandemic occurred at a time when the cohort aged 50-64 years was particularly large (as discussed further below), reflecting earlier birth peaks. This age group brings a wealth of skills and experience to the workforce, leaving a gap for employers to fill. Before the pandemic economic inactivity amongst this age group was declining, with one key factor being the rise in the State Pension Age for women, from 60 to 65 and then to 66. The trend for a reduction in economic inactivity went into reverse with the Covid-19 pandemic. Some sectors have been hit harder than others: the largest absolute numbers of workers aged 50 years and over are in education, health & social work, manufacturing and wholesale & retail, which together account for nearly half of older workers at the national scale.

Why don’t the economically inactive want to work?

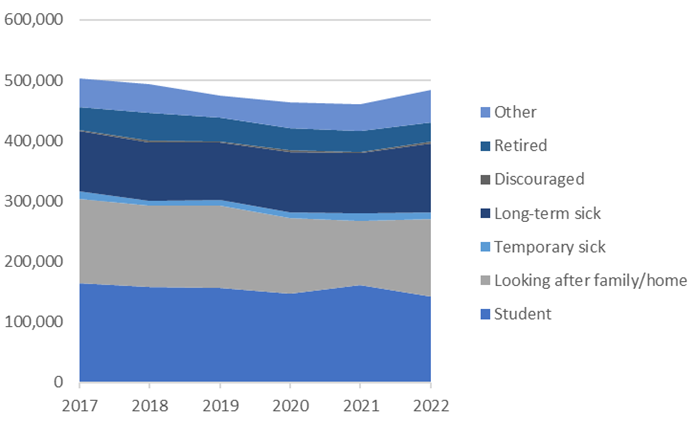

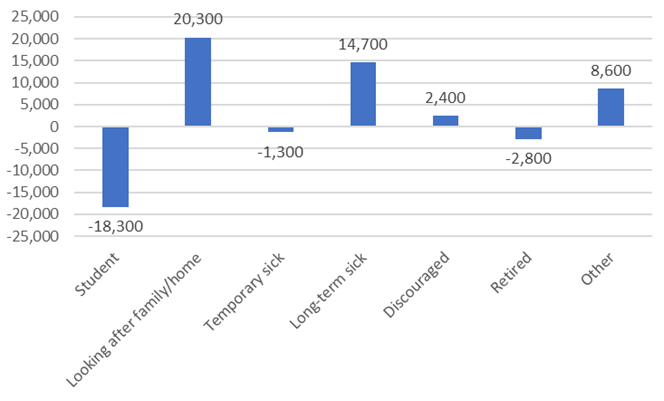

It is instructive to examine reasons why people are economically inactive. The figure below shows reasons for inactivity over the time period for the economically inactive aged 16-64 years in the West Midlands metropolitan area over the period from 2017 to 2022. There are three main reasons for economic inactivity: studying (accounting for three in ten people), looking after the family/home (accounting for one in four people) and long-term sickness (accounting for around one in four people). Most notably over this period has been a steady upward trend in long-term sickness as a reason for economic inactivity. Analyses by the Office for National Statistics indicate that the increase in long-term sickness or disability makes up a substantial proportion of the overall increase in economic inactivity nationally.[3] In the West Midlands metropolitan area, the second figure below shows that the largest annual increases in responses provided by economically inactive residents as reasons for inactivity between 2020 and 2021 were for looking after the family/home, long-term sickness and others, while the largest single decrease was for studying.

Reason for economic inactivity for economically inactive aged 16-64 years in the West Midlands metropolitan area, 2017-2022

Change in reasons for economic inactivity for economically inactive aged 16-64 years in the West Midlands metropolitan area, 2021-2022

The reasons for economic inactivity vary by age (and sex). Much of the recent policy debate on economic inactivity has focused on the over 50s.

In part, this reflects the fact that this age group represents a growing section of the population: the number of people aged 50-64 years in the West Midlands metropolitan area increased from 473.6 thousand in 2017 to 516,300 in 2022. The economic inactivity rate for this age group decreased from 29.1% in 2017 to 26.4% in 2019 before increasing to 30.1% in 2022.

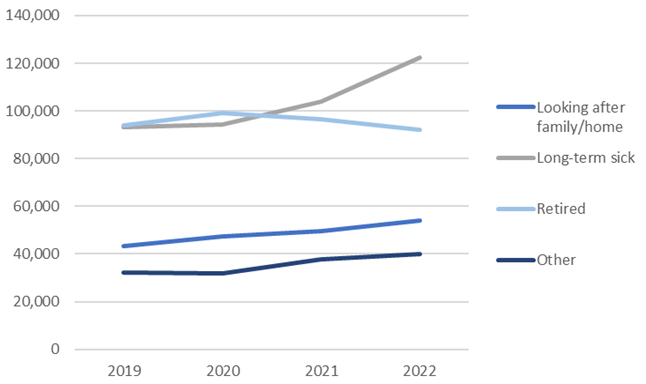

Analyses at the West Midlands region scale show trends in the main reasons for economic inactivity for those aged 50-64 years over the period from 2019-2022. The figure below shows that in 2019 the two main reasons most commonly cited for economic inactivity were retirement and long-term sickness; each accounted for nearly 35% of the age group. While the number citing retirement remains substantial, the most marked increase is in long-term sickness, which accounted for nearly 39% of the economically inactive aged 50-64 years in 2022. The numbers citing looking after family/home and other reasons also increased.

Overall, only around 15% of economically inactive residents in the West Midlands region indicated in 2022 that they wanted a job. This emphasises the scale of the challenge in tempting the over-50s out of economic inactivity and into employment. It highlights the entrenchment of early retirement but also the increasing issue of long-term sickness amongst the economically inactive. Evidence indicates that there are considerable variations between occupational sub-groups in the likelihood of poor health impacting moves out of employment into inactivity. Only around one in five of those aged 60-65 years in professional occupations left the labour market due to poor health. By contrast, one in three of those in elementary occupations or working as operatives did so.

International comparisons

Rising economic inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic was an international phenomenon, but a subsequent reduction in inactivity is less apparent in the UK than in some other countries. A sub-group of economically inactive people in the UK, especially those who own their home, are relatively comfortable – albeit the cost of living crisis has had an impact on everyone. Others, especially those who moved from employment to economic inactivity due to poor health are not financially comfortable.

Research shows that there are significantly more negative attitudes to work in the UK than in Germany and the USA. Moreover, the pandemic appears to have had a greater impact on attitudes to work amongst those aged over 50 years in the UK. It appears that improving job quality can play an important role in stemming voluntary flows of older workers into economic inactivity, with flexible working hours and good pay being the most important factors in choosing a job.

This underscores the importance of labour demand factors in encouraging people aged 50 years out of economic inactivity and into employment.

Read the Birmingham Economic Review in full.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.