Anne Green looks at the changing economic activity of the over-50s in the UK labour market and what policy implications this creates. This blog is part of a series looking at the UK Labour Market. See also: - Why are the Over-50s Leaving the Workforce?- Labour Market Flows and Future Participation Flows - What Are the Current Challenges in the UK Labour Market and How Can They Be Addressed? - Over 50s in the labour market - International Migration and the UK Labour Market: Changes and Challenges - How do Fertility Rates and Childcare Costs Play out in the UK Labour Market?

Introduction

There has been considerable debate in recent weeks and months about levels of economic inactivity in the UK. Much of this debate has focused on economic inactivity amongst those aged 50 years over and the relative contributions of early retirement and of ill-health, alongside other factors. In late December 2022 the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee in their report ‘Where have all the workers gone?’ concluded that early retirement was the largest contributor to rising inactivity. Coupled with an ageing population, this is leading to labour supply shortages.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic labour market participation amongst older workers was increasing, particularly amongst older women, while labour market participation rates amongst younger people decreased. Since the Covid-19 pandemic the increase in economic inactivity amongst older people has reinforced the ageing effect. The UK stands out internationally in terms of the size of the increase in inactivity.

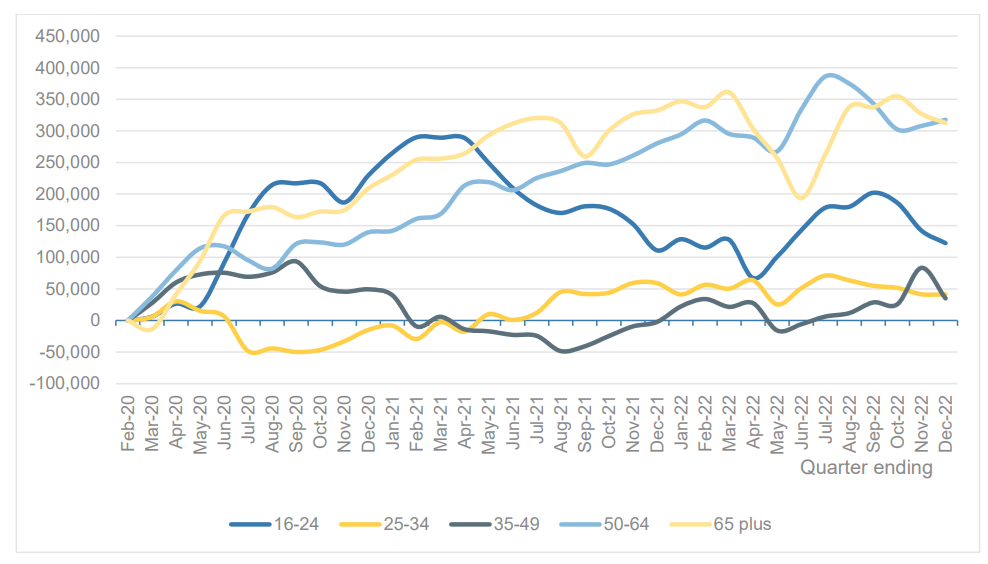

Hence, the rationale for the focus on people aged 50 and over becoming economically inactive is clear. The figure below shows that those aged 50 and over dominate the increase in economic inactivity between the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the end of 2022.

Change in level of economic inactivity by age since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (Source: Labour Force Survey, Figure 4 in IES Briefing: Labour Market Statistics, February 2023)

Demographic factors

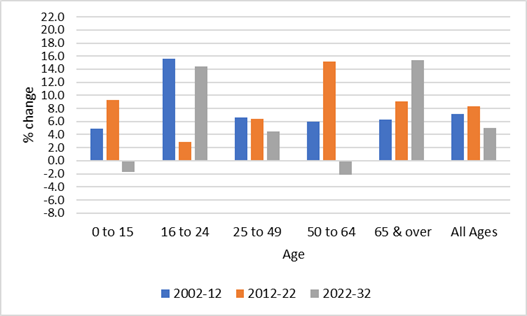

The Covid-19 pandemic coincided with a larger-than-average cohort of people aged 50-64. In the UK births peaked immediately after World War II and then again in 1964. So, in 2020 many people in this cohort would have been in their mid-50s. Hence, the reversal of the previous trend of an increase in participation rates occurred at a time when the cohort aged 50-64 was particularly large. This is evident in the figure below which shows changes in the relative size of different age cohorts in the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) area and England in three ten-year periods: 2002-12, 2012-22 and 2022-32. The general patterns of change are similar across the two areas, although the increase in the population over 65 years is more marked in England than in the WMCA area. However, it is the change in the population aged 50-64 that is most marked in 2012-22. By 2032 it would be expected that nearly everyone in this large birth cohort would be retired – even accounting for the rise in the State Pension Age – and there will be a larger elderly population to support.

Percentage change in population by age group, 2002-12, 2012-22, 2022-32, West Midlands Combined Authority Area

(source: Population Estimates and Population Projections)

Percentage change in population by age group, 2002-12, 2012-22, 2022-32, England

(source: Population Estimates and Population Projections)

Understanding changes in labour market participation: early retirement, sickness and other factors

In a study on the rise in economic inactivity in people in their 50s and 60s published in summer 2022, the IFS concluded that a lifestyle choice to retire as a result of changes in preferences and priorities, possibly in combination with changes in the nature of work that make it less attractive following the Covid-19 pandemic, is the major factor explaining the increase in economic inactivity amongst people aged 50-69 years. Of course, there were other factors too. Involuntary exit played a role: IFS analysis indicates that 37% of the increase in 50-69 year olds leaving the labour force between 2017-19 and 2020 was driven by redundancies or dismissals. However, redundancies and dismissals only made up 11% of the growth in higher inactivity rates as the economy recovered. Health-related reasons for leaving the labour force accounted for 5% of the increase in economic inactivity among 50-69 year olds according to the IFS.

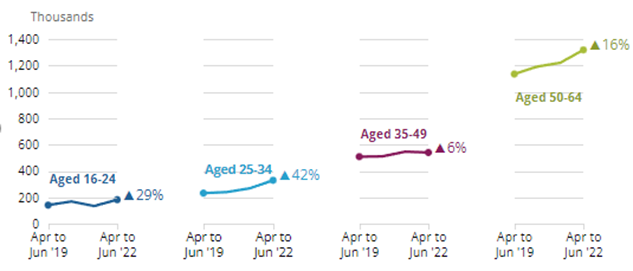

There has been a rise in long-term sickness in the UK since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic albeit long-term sickness was on an upward trend before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. Analysis by the ONS shows that in the period from the quarter ending June 2019 to the quarter ending June 2022 the number of people aged 50-64 who were economically inactive due to long-term sickness rose by 16%, from nearly 1.137 million to 1.320 million. In relative terms, however, the relative increase in long-term sickness was higher amongst the 25-34 years and 16-24 years age groups at 42% and 29%, respectively (as shown in the Figure below). In recent research on The Great Retirement or the Great Sickness, LCP point to a marked growth in people self-identifying as long-term sick and a growth in the numbers of people previously categorised as short-term sick becoming long-term sick. However, analysis by ONS reveals that most people who became long-term sick in 2021 and 2022 were already out of the workforce.

Change in economic inactivity owing to long-term sickness by age group, UK, 2019-2022

(source: Labour Force Survey, ONS 2022, Half a million more people are out of the labour force because of long-term sickness)

While there is some dispute amongst commentators regarding the extent to which long-term sickness, as opposed to early retirement, contributed to rising economic inactivity amongst people aged over 50 years during, and in the aftermath of, the Covid-19 pandemic there is consensus on the fact that pressure on the NHS is likely to be a factor contributing to the increase in long-term sickness. An ageing population puts pressure on the NHS in any case while the Covid-19 pandemic has led to disruptions in the management of chronic diseases, waiting times for routine treatment have been extended and longer waiting times to initial diagnosis mean that individuals will likely be sicker before any treatment starts. Moreover, research from Phoenix Insights suggests that the UK has experienced relatively poor access to health care since the Covid-19 pandemic in comparison with other countries.

The ONS has conducted an Over 50s Lifestyle Study to gather more information from adults aged 50 and over in Great Britain to better understand their motivations for leaving work and whether they intend to return. Analysis conducted in August 2022 on adults aged 50 to 65 years who left or lost their job since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (in March 2020) and had not returned to work showed that only a small minority were looking for work at the time of the survey – 14% of those aged 50-59 years and 6% of those aged 60-65 years. A key reason for not returning to work was retirement, cited by 37% of 50-59 year olds and 60% of 60-65 year olds. However, the number of respondents who indicated that they would consider returning to work was higher than the number of those who were actually searching, with marked variations by sub-group apparent: 86% for 50-54 year olds, 65% for 55-59 year olds and 44% for 60-65 year olds. However, over half of these respondents had not looked for a job since leaving the labour market.

The figure below shows the most important factors cited by people aged 50-65 years who had left their job since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and had not returned; (respondents could select more than one option and only the most popular options are shown). The importance placed on flexible working hours is apparent, particularly for those in the oldest age groups. Good pay and permanent employment are also among the most commonly cited factors, especially at the younger end of the 50-65 years age range. This highlights the importance of labour demand factors in encouraging economically inactive people aged 50 years and over back into employment.

Most important factors in choosing a paid job by age group, Great Britain, 2022

(source: Over 50s Lifestyle Survey, ONS 2022, Reasons for workers aged over 50 years leaving employment since the start of the coronavirus pandemic – Office for National Statistics)

The UK experience in an international context

Rising economic inactivity during the Covid-19 pandemic was a common experience internationally. However, in several countries inactivity rates have fallen since a reduction is less apparent in the UK. Research by Phoenix Insights on What is driving the Great Retirement?, based on polling of residents aged over 50 years in the UK, Germany and the USA, with a booster sample of 50-64 year olds who are not in the workforce, showed that:

- There are significantly more negative attitudes to work in the UK than in Germany and the USA and views towards work have been changed more profoundly by the Covid-19 pandemic. 58% of workers in the UK said they liked their job, compared to 74% in the USA and 73% in Germany. 42% of UK respondents who left the workforce after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic said that they retired simply because they did not want to continue working compared with 33% who retired before the Covid-19 pandemic. In the UK older workers’ views seem to have been changed more by the Covid-19 pandemic than was the case for their counterparts in the USA and Germany: 40% of workers in the UK said that the coronavirus pandemic made them rethink how they view working, compared to 28% in the USA and 30% in Germany.

- Reasons for leaving the workforce also differ. Looking at the most common answers for leaving the workforce, 25% of UK respondents said they chose to leave the workforce because they did not want to continue working. In the USA the most common responses amongst workforce leavers were they had reached retirement age (26%) or were unable to work due to health reasons (26%). Amongst German respondents, the most common response was being unable to work due to health reasons (37%). In the UK respondents were more likely to cite multiple factors for leaving than in the USA or Germany.

- Relatively higher levels of financial comfort are evident amongst 50-64 year olds in the UK than in the comparator countries. 18% of economically inactive respondents in the 50-64 years age group in the UK reported being a lot or somewhat better off as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic compared with 8% of respondents in the USA and 4% in Germany. The polling also suggests that home ownership plays a role in decision-making about when to retire and/or reduce their hours of work, so emphasising underlying socio-economic inequalities in decisions about retirement. The influence of (non-) home ownership is greater in the UK than in the USA and Germany.

Overview and policy implications

The Covid-19 pandemic impacted everyone – whether in employment or not. For those in employment, the pandemic provided an opportunity to reassess their job in the light of changed circumstances. For some workers, whatever their age, this reassessment led to a re-evaluation of what they wanted from work in terms of pay, flexibility, sociability, etc. Subsequently, this could lead to an appraisal of whether their job role aligned (especially if the nature of work and the workplace changed following the pandemic) with what they wanted from work, alongside a recalibration of work-life balance. Some older workers in more favourable economic circumstances, and especially those with occupational pensions and/or who owned their homes outright, were able to, and decided to, retire early.

Of course, not all older workers were able to make such a decision. Some workers faced redundancy or had the opportunity to take voluntary redundancy and withdrew from the labour market. Older workers were more likely to be made redundant than their younger counterparts and once out of the labour market, they take longer on average to return. Some suffered ill health – whether or not related to Covid-19 – and withdrew from the labour market.

Interacting with all of the factors outlined above are household and family circumstances, including whether a partner (if there is one) is in work, caring responsibilities for, and health of, family and friends, and financial incomings and outgoings, all influence decisions on how and when to exit the labour market. Individuals’ context matters.

This suggests that policy needs to recognise the diversity of older people who are economically inactive, the reasons for their inactivity and their desire (or otherwise) to return to the workforce. There is a clear distinction between those who have withdrawn from the workforce voluntarily before State Pension Age and have the financial capability to sustain their desired lifestyle and those who have left low-paid work because of ill health and who are not financially comfortable. The Learning and Work Institute suggests that this latter group needs individually tailored support via trusted institutions. There is a role for place-based policy here through shaping the local employment support offer and aligning it with other local provisions, including integration with health services and tailoring the skills offer to the needs of local employers, to help people back into work. The Resolution Foundation points to the role of access to tax-relieved financial pension wealth from the age of 55 years as helping to support early retirement of the former group and suggests that reforms to private pensions and the capping of tax-free lump sums may be pressing policy priorities here.

On the demand side of the labour market improving job quality has a role to play in stemming out-flows of older workers from employment and also encouraging people to return to the workforce. ‘Good work’ is important for all age groups but arguably it is particularly so for older workers who are more likely than younger workers to have health issues and/or caring responsibilities.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.