Tasos Kitsos comments on the latest ONS release of employment on zero-hours contract.

On March 15 2017, ONS released its latest estimate (Oct to Dec 2016) of people employed on contracts that do not guarantee a minimum amount of hours. Ready? Here it is…

905,000 (or 2.8% of those employed).

The figure itself may not mean a lot. Contracts without a minimum of hours to work existed for a while before we become aware of them! What is more interesting however are the trends and the statistics attached to these figures, together with a philosophical (but very real) need to reconsider what the employment rate is and whether it matters.

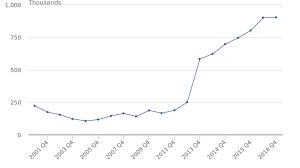

Starting from the beginning, the 905,000 people in contracts not guaranteeing minimum hours (a.k.a. zero hour contracts) is 13% higher from the relevant figure for the same period in 2015 (804,000) and a few hundred percent higher than before 2013. The very important and relevant disclaimer from the ONS regarding this data is that these figures are self-reported and hence depend a lot on people’s awareness of the term “zero-hour contract”.

Below, for example, is a graph from the ONS (ONS, 2017, p.4) showing a sharp increase since 2011 and especially between 2011 and 2013. Part of this increase can logically be attributed to increasing awareness of the term. However, this is more difficult when we discuss the 13% increase from 2015 to 2016.

The people and the sectors using these contracts are the usual suspects of underemployment. Young people, women, those in education, and those working in accommodation, the food industry, health and social work, and transport.

And what is more alarming is that a third of these people want to work more hours, especially in their current job!

Unfortunately though the bad news does not end here. The really bad news is that the definition of employment considers a person as “employed” if they have done SOME paid work during the reference week of the study. This means that you may be employed and work an hour per week.

This is to say that whilst we celebrate having more people in gainful employment than ever before, there could easily be a growing number of us being closer to “unemployed” than indeed “employed”. This is a typical example of game-playing the indicators which many countries engage in, particularly with headline indicators such as GDP and employment rates.

However, if we want to avoid surprises of social unrest, we need to carefully examine metrics of employment, look behind the headline figures and identify what they really mean. One step closer to this are the publications of working hours which allow the construction of full-time equivalents as well as median wages, but they still tend to suffer from missing or inaccurate information.

Until then, we will have to combine information from multiple quantitative and qualitative sources to get an accurate picture of employment, underemployment and unemployment.

ONS (2017) People in employment on a zero-hours contract: Mar 2017. Available here.