A recent survey I conducted of employers in Coventry in the West Midlands found that while 80% of the businesses we interviewed had hard-to-fill job vacancies, less than 5% had employed a refugee and nearly one-third had never even considered hiring one.

Yet, for most refugees, integration into their new home is heavily dependent on having a job. Finding employment is not only essential for refugees’ autonomy, but it can also improve language skills, increase cultural awareness, build local and social networks, and improve physical and mental health.

If someone has refugee status they are legally entitled to work in the UK. Anyone given refugee status in the UK will also have a National Insurance number and is permitted to work at any skill level. Employers need to obtain documentation to verify that the person has the right to work in the UK.

Asylum seekers, on the other hand, can only apply for permission to work if they have waited for more than 12 months for an initial decision on their claim. If permission to work is granted, it only allows them to do jobs on the UK’s “shortage occupations list” – specific fields in which there are staff shortages.

We surveyed 205 employers in Coventry on behalf of MiFriendly Cities – an initiative looking to enhance the contribution of refugees and migrants across the West Midlands. We found that while there is a skills gap in the area, many employers were put off employing refugees, and migrants from outside the EU, or hadn’t even considered it.

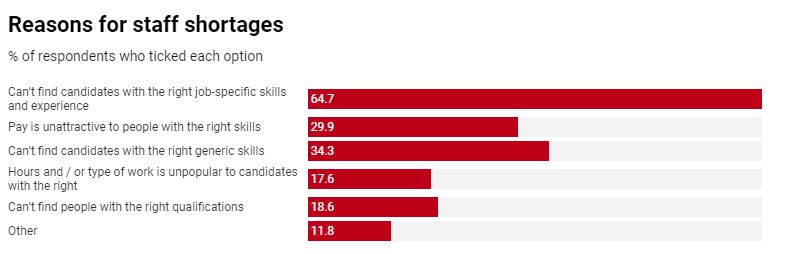

Over 80% of the employers who responded to the survey told us they were currently “definitely” or “somewhat” experiencing vacancies that were hard to fill. Sales and customer service roles were the most difficult to recruit for, with almost one-third of respondents finding this challenging. Unemployment in the UK is currently at an all-time low, which emphasises these hard-to-fill vacancies.

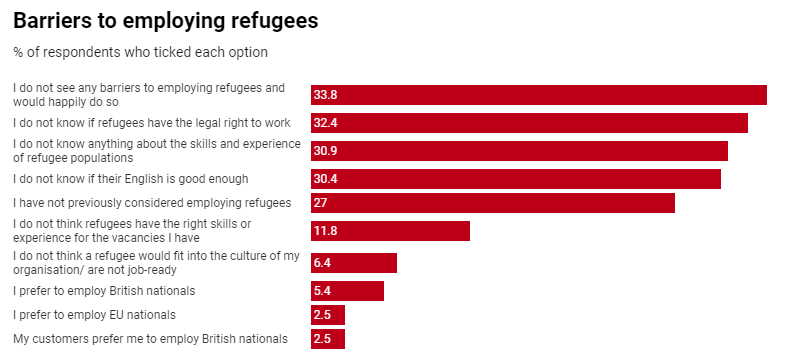

Refugees and former refugees – those who have been granted indefinite leave to remain – were employed by less than 5% of the employers we surveyed. But more than half employed migrants from the EU, and one-fifth employed non-EU migrants. This supports research that refugees are more likely to be unemployed than other migrant groups. In our survey, 27% of employers had not even considered employing refugees.

Refugees and non-EU migrants are especially likely to be unemployed or under-employed. In a comparable study in Birmingham, up to 65% of male refugees and up to 80% of female refugees face unemployment. Many refugees who come to the UK hold professional qualifications or have years of experience of working in a particular profession. Yet refugees who arrive in the UK with skills in demand in the UK economy such as teachers, doctors and nurses, often do not practice professions in the UK. This is likely to be due to them facing a number of barriers, such as the erosion of skills for those who have waited a long time before a decision on their asylum claim, insufficient English language skills or unfamiliarity with the UK market.

The high level of EU migrant employment by those we surveyed raises concerns that the skills gap could be widened by Brexit, if migrants chose to leave the UK. Recent research has estimated that almost a million EU citizens who work in the UK, many of whom are highly qualified, could be either planning to leave the country or have already decided to do so following the result of the EU referendum.

Only one-third of employers reported they didn’t see any barriers to employing refugees. The rest reported some kind of barrier to employing them, or had not considered employing refugees. One-third said not knowing whether refugees had the legal right to work might act as a barrier to their employment.

Getting the facts straight

Nearly all the employers we surveyed were not confident in employing non-EU migrants, including refugees based in the UK and those who do not have a UK passport, because they have not received training or support on this.

Over half of employers want more information on immigration law and employment regulations. Part of this is likely to stem from fear of penalty: a system of fines was introduced under the 1996 Asylum and Immigration Act for employers hiring staff without the appropriate documentation. Refugees need to provide employers with their biometric residence permit which proves their eligibility to work. Other documents may also need to be provided, depending on the length of leave to remain granted, and for asylum seekers. This can make some employers reluctant to employ refugees because of the burden of checking this information, confusion around the law, or because they are concerned that they might be in breach of the legislation.

Our findings show that close collaboration between local authorities, migrant support organisations and employers is crucial to successful labour market integration of refugees and non-EU migrants. Where these people don’t already have the skills required, apprenticeships could also play an integral role in tackling the skills gap problem.

In order to help employers to hire refugees and migrants from outside the EU, and to improve their confidence in doing so, they need education and support around the law, along with more information on migration policy. This should also focus on making employers aware of the skills and experience of refugees in order to increase the number who consider employing them and increase their confidence in doing so. Critically, refugees must be made part of the process in identifying solutions to the obstacles they face.

Catherine Harris, Assistant Professor, Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University and a City-REDI Associate.

You can view more of Catherine’s work below:

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()