What is the scale of the homelessness problem in the UK?

Britain is in the midst of a homelessness crisis, with 320,000 citizens – that is, 1 in every 200 people – without a fixed place to sleep [i]. The number of people in this condition is rapidly growing, having more than doubled since the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition came to power in 2010. For this to be happening in one of the wealthiest countries in the world signals deep political failures, and calls upon further research to understand what government policies are having the greatest effect of forcing people out onto the streets – as well as what interventions at the local level can tackle this problem, at a time when all of the government’s energy is directed towards delivering Brexit.

What are the impacts of homelessness on the individual?

Living on the streets is incredibly dangerous. According to the charity Crisis, the average life expectancy for a homeless person is 47 years, and homeless people are almost 17 times more likely to have been victims of violence [ii]. Many of us will have seen, or at the very least heard about, the daily injustices that homeless people face: not only verbal and physical abuse on the street but also higher rates of sexual and substance abuse. There is also the growing trend of hostile architecture to contend with. Developers are increasingly modifying spaces to make it impossible for homeless people to rest there, such as spikes or stones embedded into window sills and floors, benches with armrests along them to prevent people from lying down, or water sprinklers and loud tannoy announcements to make it an environment unfit for resting. This is before we consider the privatisation of public space; exact figures do not exist as local authorities are reluctant to disclose details, but CBRE research shows the spread of privately-owned public spaces in British cities where security guards can legally force people to leave. Typically, this means homeless people, along with protestors too [iii].

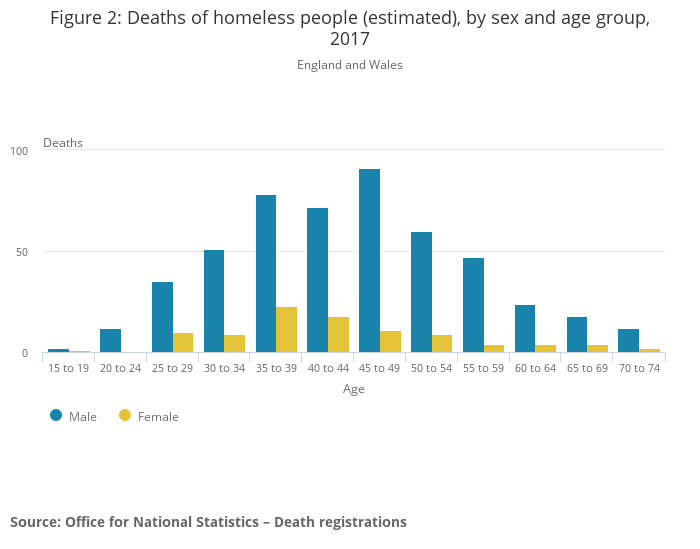

Statistics released by the ONS in late December 2018 estimated that 597 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2017, an increase of 24% since 2012 [iv]. 84% of all rough sleepers who died in 2017 were men. Common forms of death were drug overdose, liver disease (typically caused by long-term heavy alcohol consumption) and suicide. Deaths from drug poisoning, in particular, have increased substantially, to the extent that over half of deaths are now caused by heroin overdose. The ONS dataset showed that the idea that homeless people are most at risk of death in winter is false; in fact, there is very little seasonal variation in morbidity rates, suggesting that it is not exposure to the elements that is killing Britain’s homeless but rather exposure to addictive substances and a lack of support services to help them cope.

What causes homelessness?

People can become homeless for a variety of reasons. It can be after discharge from the military with no support network to return to and a lack of mental health services for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; unmanaged mental health issues making it difficult for individuals to hold down a job; substance addiction; the breaking down of family or romantic relationships; and the loss of a job without any savings to act as a safety net. There are also a number of social factors that contribute to homelessness. Research by Tom Slater at the University of Edinburgh talks about “Right to Buy”, which has led to a severe shortage of social housing in the UK, coupled with other recent Conservative policies such as the “Bedroom Tax” forcing vulnerable people into extreme poverty, and therefore greater risk of homelessness [v]. There is also the chaotic launch of Universal Credit that is pushing poor citizens into destitution and dependency upon food-banks, along with a massive pressure on the property market owing to overseas investment, “Help to Buy” inflating property prices and the mismatch between rent increases and stagnating wages in Britain. The distinction the government makes between the “deserving” poor, who are destitute through no fault of their own and therefore deserving of assistance, and the “undeserving” poor who have character flaws that make them responsible for their own destitution [vi], is also a problem. This toxic division of citizens totally ignores structural forces beyond an individual’s control that can mean any one of us could end up homeless. Indeed, a recent UN report blasted the UK government for its “punitive, mean-spirited and callous approach” towards the poor.

Why is the homelessness crisis connected to “neoliberal austerity”?

Why then should homelessness be characterised as a product of neoliberal austerity? At its core, neoliberalism is an economic and political ideology that seeks to radically redefine the relationship between the state and the citizen. The state is rolled back from areas it was previously active in and the market and private capital are encouraged to fill the space left behind. This is enforced through the state’s instruments of control (the law, military and police services) which defend the interests of businesses and rich individuals. Those with the fewest financial or social resources are underprivileged in multiple intersecting ways – and the neoliberal state withdraws itself from effectively addressing these, instead preferring to deregulate and leave such issues to the market.

Neoliberal ideology was born in the era of Thatcher and Reagan. Critical analysis of policies shows that this is now firmly entrenched in governments and international institutions across the world [vii]. My own research in a paper I am working on shows how this wealth is accumulating among multinational corporations and a very small ultra-rich class who are their beneficiaries, with capital and assets being held through shell companies in offshore tax havens to minimise tax payments on this wealth. Wealth inequality is rapidly increasing, which has impacts on health outcomes, reduces social mobility and undermines trust in institutions. In effect, neoliberalism is the state subsidising the private fortunes of the rich. Privatising public assets in ideologically-driven sales at very low prices to private investors, even when there is no real business case to do so, means that the public sector is deliberately left with limited capacity to act. Austerity further shrinks the state and means that charities are left to attempt to address complex problems such as homelessness and substance dependency. City-REDI’s research in Wolverhampton found that it is government cuts to social services and mental health support that act as a key driver of homelessness, and as has previously been demonstrated, these issues ultimately cause unnecessary deaths on the street when left unaddressed. The scandal of thousands of people risking their lives to sleep on the streets of Britain shows us the growing extent to which the UK government has abandoned its moral duty to care for the most vulnerable citizens of our country. Some local leaders are already talking about it, most notably Andy Burnham at the Greater Manchester Combined Authority who is putting this issue on the agenda. What is needed now is visionary leadership in local authorities across the country that seeks to repair the damage caused by a neglectful central government.

This blog was written by Liam O’Farrell, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The opinions presented here belong to the author rather than the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

[i] Shelter (2018) ‘320,000 people in Britain are now homeless, as numbers keep rising’.

[ii] Crisis (No date) ‘About homelessness’.

[iii] CBRE (No date) ‘Privatisation of public space’.

[iv] ONS (2018) ‘Deaths of homeless people in England and Wales: 2013 to 2017’.

[v] Slater, T. (2016) ‘The housing crisis in neoliberal Britain: free market think tanks and the production of ignorance’ in Springer, S., Birch, K. and MacLeavy, J. The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.370-382.

[vi] Bridges, K. M. (2016) ‘The deserving poor, the undeserving poor, and class-based affirmative action‘, Emory Law Journal, 66(1049).

[vii] Robinson, W. I. (2007) ‘Beyond the theory of imperialism: global capitalism and the transnational state’, Societies without Borders, 2, pp.5-26.

3 thoughts on “Homelessness – the human cost of neoliberal austerity”