Abigail Taylor discusses fertility rates and childcare costs within the UK Labour Market comparing the findings internationally. This blog is part of a series looking at the UK Labour Market. See also: - Why are the Over-50s Leaving the Workforce?- Labour Market Flows and Future Participation Flows - What Are the Current Challenges in the UK Labour Market and How Can They Be Addressed? - International Migration and the UK Labour Market: Changes and Challenges - Changing Labour Market Participation of People Aged 50 Years and Over

Declining fertility rates in the UK and internationally

The total fertility rate in the UK has been below replacement level since 1973 and decreased year on year between 2012 and 2020 according to data from the Office for National Statistics. Replacement fertility refers to the level of fertility required for the population to replace itself in size in the long term. In the UK, to ensure long-term ‘natural’ replacement of the population, women would need to have, on average, 2.08 children. The total rate in 2021 was 1.61 children per woman.

With people living longer, countries with fertility rates below replacement level risk averse effects on public finances and standards of living. Where there is an elderly population with substantial health and social care the costs of supporting them will fall on a smaller group of workers. These countries also risk struggling to have enough young people entering the workforce to replace those reaching retirement age. Without increasing the economic activity rate by getting older people back into the workforce or reducing youth unemployment, then countries will either need to increase net migration or face the consequences of a reduced workforce. An important counterbalance to relatively low fertility rates in the UK over recent decades has been migration.

Research by the House of Commons Library shows that since 1997 immigration and emigration have increased to record levels, with immigration exceeding emigration by more than 100,000 each year between 1998 and 2020.

While fertility rates increased overall in 2021 in the UK, younger age groups saw a decline in fertility rates, whilst rates increased in older age groups. Since 2003, fertility rates have been highest among women aged 30 to 34. Since 2013, fertility rates have been higher among women aged 35 to 39 than those aged 20 to 24. In 1997, the fertility rate in the older age group was around half that of the younger group.

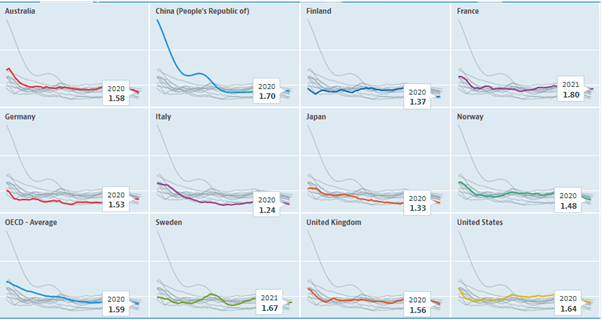

Data from the OECD shown in the chart below indicates that declining fertility rates are not a UK-specific issue. Indeed, the average fertility rate across the OECD fell by 44% between 1970 and 2020.

This has been attributed to generous social policies and egalitarian values. However, fertility rates have fallen across Nordic states since 2008. This “can be partly explained by the rising importance individuals assign to work as a source of value and meaning in life”.

According to the World Economic Forum, three main factors contribute to falls in fertility rates worldwide: women’s empowerment in education and the workforce, lower child mortality and the increased cost of raising children. Research by the National Bureau of Economic Research cited in the Economist suggests that public measures to support women in the workforce, family policies such as reducing childcare costs, and “co-operative fathers and favourable social norms” can reverse a declining fertility rate.

What are the economic and social benefits of investing in accessible, affordable and good-quality childcare?

“Childcare is not a family issue, it is a business issue. It affects how we work, when we work, and for many, why work. Moving forward, employer provided child care could also influence where we work” (Harvard Business Review, 2021)

Evidence suggests that GDP in the US could increase by 5% if women participated in the workforce to the same extent as men. According to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, providing childcare to women could add $3 trillion dollars to the global economy per year. Few studies have quantified the impact on productivity from childcare-related career-breaks in the UK but evidence provided to the Treasury Commons Select Committee by HM Treasury in 2018 suggested that if men and women participated in the economy at the same levels, GDP could increase by 10% by 2030. The Select Committee report indicates that whilst increasing the proportion of parents working will increase economic output, such a move will only increase productivity if their output exceeds that of the existing workforce. Almost half of non-working mothers in the 2021 Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents said that if they could arrange good quality childcare that was convenient, reliable and affordable, they would prefer to go out to work. 1.6 million women with young children are estimated to be currently held back from working more hours by a lack of suitable childcare according to the Centre for Progressive Policy. However, it must be acknowledged that not all mothers want to work.

The OECD recognised the positive economic and social benefits of investing in early childhood education and care (ECEC) when it argued:

Expanding childcare infrastructure could be an important source of new jobs. The World Bank has argued that increasing the childcare workforce to respond to current demand could create up to 43 million new jobs in high, upper middle, lower middle and low income countries. Investing in childcare could also offer ways for companies to attract new staff and retain existing staff. Expensive childcare can make it difficult for families to escape poverty even when they are in full-time work.

How does the cost and take-up of childcare in the UK compare to other countries?

OECD evidence suggests that high childcare costs can contribute to inequalities in childcare use across income groups. The UK is one of several countries – alongside Finland, France, Ireland and Switzerland – where the participation gap between low-income and better-off households is over 50%. Availability of childcare, cultural norms, parents’ labour market prospects and, in some countries, the availability of lengthy homecare allowances can influence the use of formal childcare.

In the UK, according to the 2021 Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents, children in the most deprived areas and in families earning under £10,000 were less likely to receive formal childcare than children in families from less deprived areas and in families earning £45,000 or more. This is likely to not just be the result of high childcare costs in the UK; the value some parents place on childcare provided by family members also plays a role.

This blog has shown that:

- Like many western countries, the UK has low fertility rates. There is evidence that global falls in fertility rates are linked to women’s empowerment in education and the workforce and the increased cost of raising children.

- The UK stands out internationally in terms of high cost of childcare, and inequalities in childcare use across income groups.

- Childcare can be a barrier to employment for parents, particularly women. Economic and social benefits exist for why governments should invest in accessible, affordable and good-quality childcare. Cutting childcare costs could support efforts to improve productivity rates.

According to Melinda French Gates “[I]t’s time to start treating childcare as essential infrastructure – just as worthy of funding as road and fiber optic cables. In the long term, this will create more productive and inclusive post-pandemic economies”.

The government introduced a package of measures designed to increase childcare support for parents, boost the number of childminders and drive take-up of childcare offers, to address rising costs. However, achieving substantial change is likely to require more ambitious strategy and reform. For example, the Family and Childcare Trust is calling on the government to extend the current 15 hours of free childcare per week to all two year olds, rather than just the most deprived to support working parents and extend childcare support to parents undertaking training, education and volunteer roles.

Changes in work are likely to exacerbate challenges with current provision. Increases in hybrid and remote working emphasise the importance of developing childcare outside of the existing office day. Companies could seek to foster employee engagement, satisfaction and retention through developing childcare infrastructure as well as wider programmes that encourage peer-to-peer support and learning. Businesses could more broadly recognise that childcare issues do not just impact parents with children below school age but up to 18.

National, regional and local government could seek to make it easier for parents to enter and sustain employment through other types of support such as improving public transport provision, reducing the cost of public transport and ensuring access to high-quality skills and careers training and advice.

This blog is part of a series looking at the UK Labour Market. See also:

- Why are the Over-50s Leaving the Workforce? – Labour Market Flows and Future Participation Flows

- What Are the Current Challenges in the UK Labour Market and How Can They Be Addressed?

This blog was written by Abigail Taylor, Research Fellow, at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.