Professor Anne Green outlines the skills shortage in the space sector, the types of skills needed, how the industry can attract a wider pool of recruits and what opportunities are available in the West Midlands and beyond.

This blog has been produced to provide insight into a City-REDI / WMREDI project looking at the development of a Space Cluster in the West Midlands. The project is led by Dr Chloe Billing and colleagues:

View more work from the Local Space Cluster Development Support Programme

Introduction

The space sector is experiencing continuing growth. As such, it should be an attractive sector for new entrants to the labour market. Also, at a time when various other sectors have seen a downturn in demand due to the Covid-19 crisis, job opportunities in the space sector should appeal to workers with relevant skills seeking to move elsewhere and to those interested in upskilling and/or reskilling. Yet the space sector faces skills deficiencies. In part, this is due to the high level, specialised nature and mix of skills required, and to the demand for similar skills from other sectors. This underscores the need for firms in the space sector – nationally and regionally – to consider carefully what more they can do to meet their skills needs. This means examining recruitment, training, skills utilisation and retention. This study provides information on the number and types of higher education courses in the West Midlands of relevance to the upstream and downstream space applications, while the 2020 Space Census and the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020 provide recent insights into skills issues in late 2019 and early 2020 at the national level. All of these sources are drawn on here.

Types of skills needed

The space sector is characterised by a highly qualified workforce, often with graduate and postgraduate qualifications. While some space sector firms require one or more specific space specialisms – such as satellite imagery processing and interpretation, orbital mechanics, launch operations, space system engineering, etc., there is also strong demand for generic technical skills – such as data science, AI techniques, software engineering, etc. These generic technical skills are also in demand across a range of manufacturing and services sectors. An underpinning breadth of scientific understanding, primarily in maths and physics, is particularly important in the space sector. Yet ‘scientific’ skills alone are insufficient for many roles in the space sector. Other skills, such as ‘agility’ and communication and collaboration skills, are increasingly valuable for businesses, along with commercial awareness and business acumen. Moreover, given that on the job learning plays an important role in the space sector, there is a need for mentoring and teaching skills. The challenges of hiring people with a ‘hybrid skills’ set (i.e. both sector-specific specialisms and non-sector specific skills) are exacerbated when recruiting for those roles requiring a specific combination of skill sets. Findings from the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020 reveal demand for ‘transferable skills’ as well as for ‘specialised skills’ amongst firms in the space sector recruiting staff in late 2019 and early 2020. In a similar vein, an analysis of 812 early-career UK space sector job adverts using a competencies taxonomy, identified software development and data analysis skills as the technical skills that were most sought after. The same analysis reveals a high demand for interpersonal and communication skills. Chiming with the findings of an Industrial Strategy Council report on the UK Skills Mismatch examining the economy as a whole, the space sector requires both technology and people (including management and leadership) skills.

Skills deficiencies

Skills deficiencies comprise skills gaps in the existing workforce (i.e. in the internal labour market) and skill shortages in the external labour market. According to the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020, the most frequently cited skills gaps in scientific, engineering or technical functions in the existing space sector workforce were in software engineering, radio frequency engineering, systems engineering, engineering or electronics design, electronic engineering at professional level, and AI and machine learning. The most commonly cited difficulties for those space sector businesses citing difficulties recruiting on the external labour market were first, applicants lacking required experience; secondly, applicants lacking required specialist skills, knowledge or qualifications; and thirdly Brexit reducing the ability to attract people from Europe. These answers are indicative of wider skill shortages in the external labour market in the UK. The fact that ‘lack of required experience’ was the most commonly cited difficulty may be indicative of a preference to recruit rather than to train, which is evident across the UK economy more generally. The fourth and fifth most commonly cited reasons for recruitment difficulties were competition from businesses in other sectors, followed by competition from businesses in space-related activities. These responses indicate the wider demand for skills sought in the space sector. This includes the programming skills that are so sought after in the space sector. They may be symptomatic of a fear of poaching, which in turn may lead to some reluctance to invest in training.

Supply of graduates

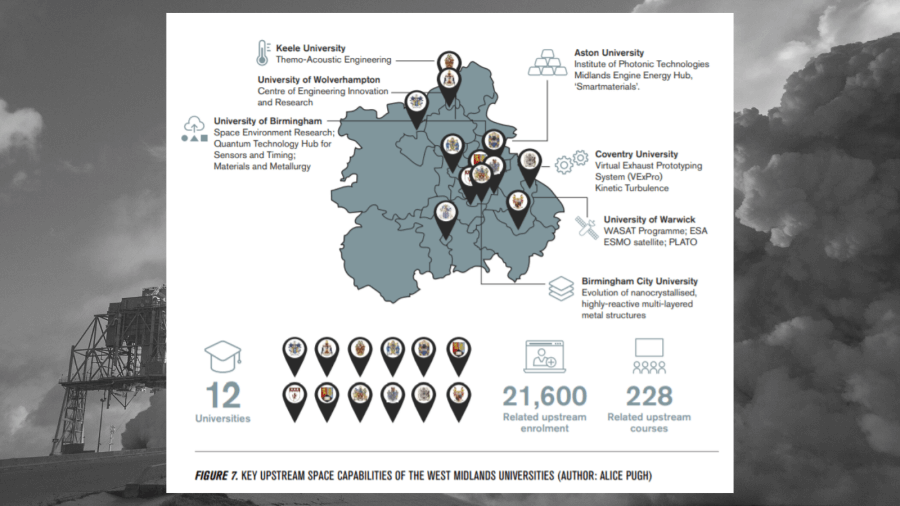

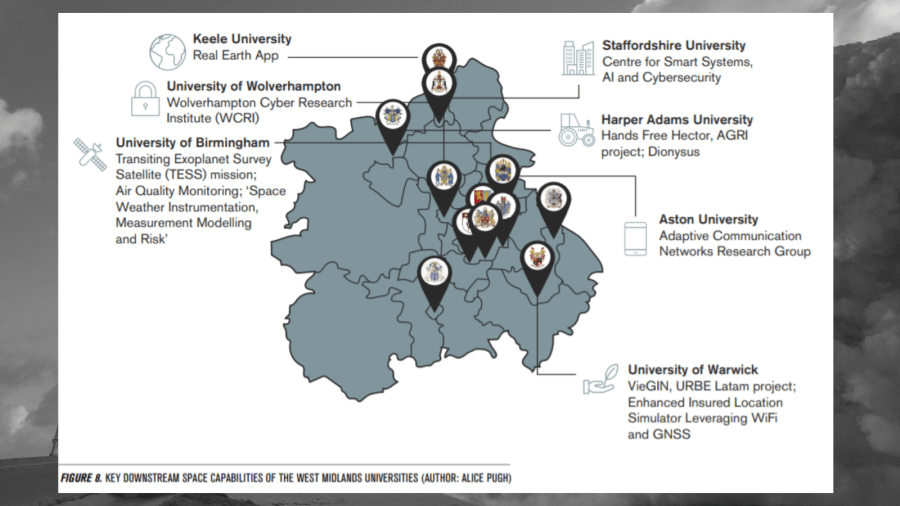

The asset mapping in the West Midlands for this report highlights a strong higher education base in the region. Focusing first on upstream activities, across 12 universities there are 228 related courses (the majority in engineering-related subjects) and 21,600 enrolments. Some universities (e.g. Birmingham and Warwick) have experience of European Space Agency funded projects and there are some good examples of links with industry stakeholders (including the University of Warwick Satellite Engineering project), including projects focusing on product development to help small businesses (e.g. the Enabling Technologies and Innovation Competencies Challenge Project at Aston). There are also a large number of downstream activities, with 12 universities teaching 491 related courses (including in business studies, engineering and technology and computer science) and 80,110 enrolments. Yet there are concerns that courses in universities, though space-oriented, lag behind industry developments in the context of rapidly advancing technologies and/or lack specificity to the space sector’s particular needs. Indeed, 40% of companies in the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020 reported gaps in current training provision, primarily at the graduate/post-graduate level, so suggesting a need for the development of postgraduate training courses aimed at developing specific skills. Yet the Survey also reveals that graduates are in plentiful supply – especially for entry-level positions.

Attracting recruits for the space sector

While the space sector has traditionally focused on recruiting highly qualified postgraduates and undergraduates, disproportionately from higher socio-economic groups and from privately educated backgrounds. To supplement the more traditional talent pipeline, it is important not to overlook other potential labour pools, including recruits with A levels and workers with experience in other sectors. Employers – especially smaller firms – prefer recruits with direct experience of working in the space sector, so narrowing recruitment. This desire for experience places some onus on the space sector to develop internship and placement programmes. Research suggests that there is a perception that entry to the sector is difficult without specialist skills, which may put off potential applicants. Recognising that shortcomings in recruitment are a barrier to growth, other sectors in the West Midlands, such as the professional and business services sector, are working to broaden their recruitment activities to attract, and benefit from, a more diverse talent pool. The 2020 Space Census shows that women are significantly under-represented in the space sector, reflecting wider trends amongst STEM students and graduates. In the West Midlands, there is particular potential to harness skills from a relatively large population of young women and men. However, the evidence suggests that the space sector is characterised by an inward-focused approach to recruitment. Work by the Space Skills Alliance on assessing the quality of space job adverts highlights that whereas most adverts provided clear information on job title, company background, job description, and person specification, they tended to be much less clear about salary details, benefits, diversity statements and the transparency of the recruitment process. These latter factors all impact on the diversity of candidates who apply. This suggests that there is scope to revise conventional recruitment methods to reach and attract a wider pool of potential applicants.

Retention

The results of the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020 show that in addition to recruitment, retention is a problem for some companies in the space sector. It seems that retention challenges are starkest in large companies. Once space sector employees have a few years’ experience they become more valuable to other space sector businesses (given the preference outlined above for workers with directly relevant experience). Moreover, after three-six years working in the space sector, some graduates realise that their work experience means that their value has increased also for employers outside the sector and with their technical and other skills, which are in demand elsewhere, they can earn more outside the sector. Uncompetitive pay is the most frequently cited reason in the Space Sector Skills Survey 2020 amongst those firms experiencing staff retention difficulties. While space sector firms often provide competitive pay to highly qualified entrants, pay rates may be less attractive as experience increases and so space firms are vulnerable to poaching for higher pay by firms within and beyond the sector.

The challenge ahead

Given that the space sector requires high level specialised technical and transferable skills, many of which are in demand across the economy, it is likely to face ongoing competition for skills. Furthermore, Brexit may mean that the UK space sector may be less attractive to European Union workers, who comprised the majority of foreign nationals working in the sector. Previous research has identified key limitations of the current space skills pipeline as encompassing a lack of awareness of the space sector, lack of opportunities to develop experience, and the mismatch between teaching useful knowledge in universities.

Opportunities

Yet there are opportunities to address skills needs in the space sector in the West Midlands (and beyond). There is scope to widen recruitment beyond conventional channels. The professional and business services sector in the West Midlands has successfully broadened non-graduate recruitment to take on people with A levels and to utilise apprenticeships – including degree apprenticeships – to a greater extent than was formerly the case. In doing so, it has begun to diversify its workforce. Employers and education and training providers have adjusted their training programmes accordingly. In the space sector, the absence of a training-supported entry route for young people at the ‘A’ level point has been identified already. In the context of the continued growth within the sector, the time would be ripe to implement this. A further key source of new talent is skilled workers with transferable skills in engineering and advanced manufacturing (notably the aerospace and automotive sectors which are particularly important in the West Midlands). Here there is potential for existing firms to pivot into the space sector. With the addition of a ‘space’ dimension to existing technical qualifications and transferable skills, there would be scope for workers made redundant/otherwise looking to change jobs to move into the space sector. Hence, alongside looking to a broader talent pool for recruitment, there is a need to address current limitations in the training infrastructure, as indicated above. In the university sector evidence from Industrial Strategy Council research on Rising to the UK’s Skills Challenges suggests that many companies value strong relationships with higher education institutions where they can help shape the curriculum and collaborate on course development and programme design, as well as offering regular placement opportunities. There are examples in the West Midlands (e.g. from the Warwick Manufacturing Group) that could be built on here. In this way students’ exposure to, and work experience in, the space sector would stand them in good stead. With regard to retention, in addition to looking at ways of making pay more competitive, non-pecuniary avenues for keeping and further developing skills include creating opportunities to work on new projects. A multi-pronged strategy to meeting skills needs for the space sector is required – current approaches are not up to the task.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.