The latest edition of REDI-Updates is out now - providing expert data insights and clear policy guidance. In this edition, the WMREDI team investigates what factors are contributing to the cost-of-living crisis and the impact it is having on households, businesses, public services and the third sector. We also look at how the crisis in the UK compares internationally. The cost-of-living crisis has become an ever-present feature of news headlines over the past year. But what does it really mean and where are we heading? Matt Lyons investigates. View REDI-Updates.

Defining the Cost-of-living crisis

The cost-of-living crisis refers to the real-term decrease in disposable income that is being observed by UK households as the cost of essential goods and services has accelerated beyond wage growth. In 2022, annual CPI inflation was 11.1% (ONS, 2022), the drivers of which are covered in detail more detail in later chapters but, in short, there are four main issues:

| ENERGY |

The most important factor driving the cost-of-living crisis has been the rapid increase in the price of fuel for domestic heating and transport, which has significantly increased predominantly due to the war in Ukraine.

|

| HOUSING |

Household services (such as gas and electricity) have also increased rapidly. The rise in private rental costs that have been observed has been attributed to demand for rental property being outstripped by supply, in part due to buy-to-let landlords leaving the market.

|

| FOOD & BEVERAGES |

Food and non-alcoholic beverages have seen prices rise by 16.4% between October 2021 and October 2022. The combination of increasing energy and transportation costs to food producers and a tight labour market has increased picking and packing costs.

|

| CONSUMER GOODS |

Supply-chain blockages due to a snap-back of demand post-COVID hindered by restrictions in China and a booming economy in the USA have coalesced to see too much money chasing too few goods. |

The Policy Response

In response to inflation, there have been two major policy interventions: one fiscal, one monetary. On the fiscal side, the Government introduced the Energy Price Guarantee as a substantial intervention, estimated to cost the UK Government up to £140 billion. The guarantee runs through the winter months from October 2022 to June 2023 protecting consumers from the full impact of price rises. The typical household is expected to see annual energy costs of £2,500 instead of £4,000, which would have been the case without intervention (IFG, 2022).

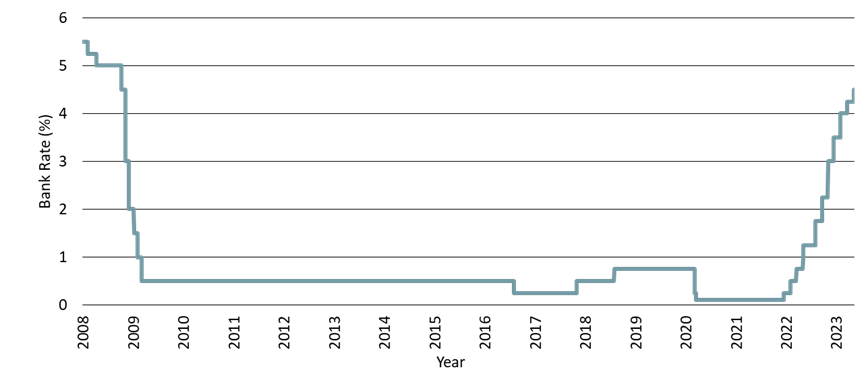

On the monetary side, the Bank of England (BoE) has been increasing interest rates rapidly from 0.25% in February 2022 to 4.5% in May 2023 to stifle demand and thus inflation through increased borrowing costs (Figure 1). The interest rate rises will impact many who are on variable-rate mortgages and those with their fixed rates coming to an end. Analysis by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2022) found that by assuming a mortgage interest rate of 5.5% (up from 3%) the average monthly mortgage payment would increase by £250, from £610 a month to £860.

Figure 1: BoE Interest Rates over 10 years

How are different groups impacted?

The impact of the cost-of-living crisis and the policy response to it is affecting some groups in society more acutely than others. Low-income groups are particularly impacted by the cost-of-living crisis because the goods and services that have increased most rapidly, energy and food, are essential goods that make up a larger share of low-income household budgets. Low-income groups have also been more severely impacted by changes to the tax and benefit system with the reversal of the £20 universal credit uplift and the rise in NI contributions disproportionately affecting low-income households. The consequences of this are severe, research by NIESR (2023) suggests that approximately 1 in 4 households are facing food and energy bills that exceed their disposable income.

Housing tenure is another important contributing factor which determines the vulnerability of households to the cost-of-living crisis. Some groups, particularly younger and less wealthy, are more likely to be in the private rented sector which is seeing rapid price rises. Alternatively, they may be first-time buyers holding large mortgages that will be due for renewal in a period of significantly higher borrowing costs.

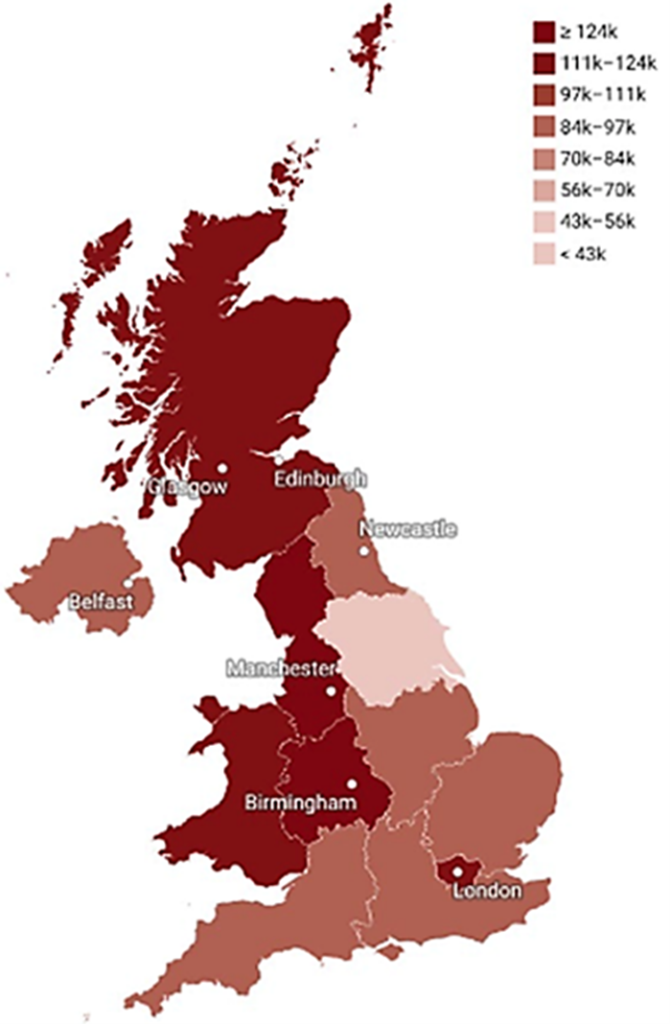

The impact of the shocks to housing, energy and food prices is spread unevenly across regions. NIESR (2023) found that responses to rising food and energy prices forecasted rates of destitution range from 18.5% in the West Midlands to 32.3% in Northern Ireland. While the West Midlands is performing relatively well by this measure, the region is one of the most exposed to rising mortgage payments wiping out household savings (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Households with No Savings as a result of higher mortgage payments.

Wages

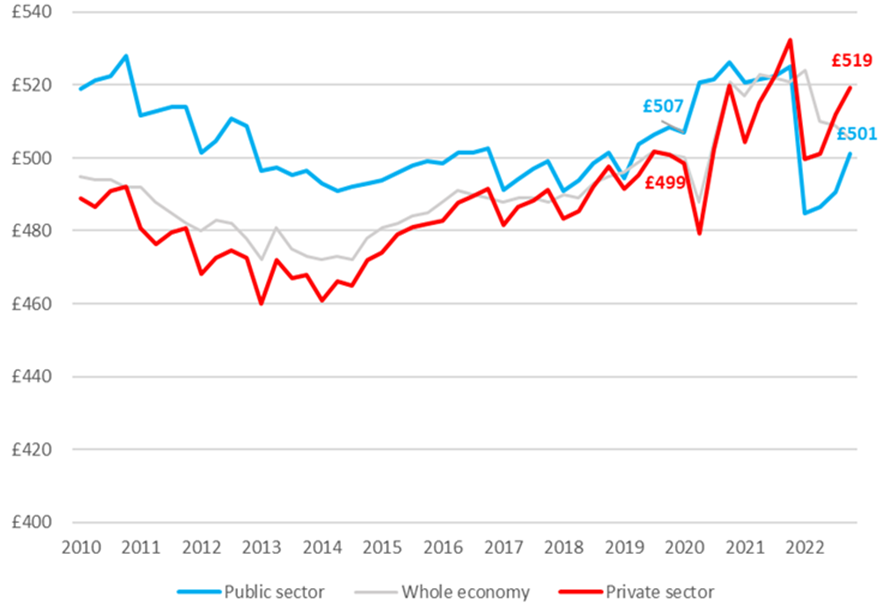

Inflation and rising interest rates are increasing costs for households, but wages are another side of the picture. Normal wage rises are being observed particularly in the private sector, however, in real terms, wage rises are modest and are falling in the public sector. Figure 3 shows the average weekly earnings adjusted for inflation of the public sector vs private sector from 2010 to 2022. The figure shows that since 2020 there has been a divergence between groups, with private sector workers seeing a 4% rise in weekly earnings (£499 to £519) and public sector workers seeing -a 1.1% fall (£507 to £501), falling behind the private sector for the first time since 2007.

Figure 3: Average weekly earnings: total pay in the public sector, private sector and whole economy from 2010 to 2022 (CPI deflated (2015=100)

What to Expect in the short-term

The confluence of high inflation, rising interest rates and lagging wage growth means that living standards have fallen across the board with the OBR (2022) forecasting a 7% fall in living standards over the next 2 years. Those with high levels of debt, and those on lowest wages are particularly vulnerable.

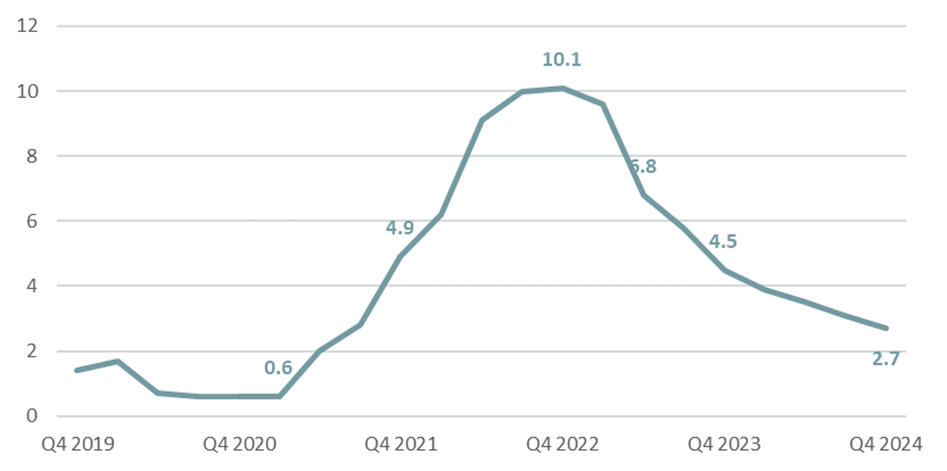

Figure 4 shows the UK inflation annual growth from Q4 2019 forecasted to Q4 2024 by the OECD. It shows the rapid rise of inflation from Q1 2021 (0.6%) through 2021 reaching a peak in Q4 2022 (10.1%). From the peak we observe inflation falling rapidly through 2023 before reaching 2.7% in Q4 2024 still over the BoE target rate of 2%.

Figure 4: United Kingdom inflation annual growth rate (%), Q4 2019 – Q4 2024

However, since this forecast, it is apparent that the inflation rate in the UK has remained stubbornly high with RPI at 8.4% in May 2023 (CPI=7.9%). The latest inflation data suggests that interest rates are likely to rise at the time of writing by another 0.25% or possibly even 0.5%. The key takeaway is that rates remain significantly above the pre-mini-budget average in autumn 2022 and this will affect housing affordability and borrowing in the short to medium term.

Inflation growth rates may be falling (albeit more slowly than expected) but prices remain well above pre-2022 levels. Some positive news, in April 2023, the Energy Price Guarantee was extended and while prices remain high forecasts suggest that the price cap will fall significantly by July 2023. In short, despite indicators slowly moving in the right direction, the cost-of-living crisis is expected to get worse before it gets better.

What to expect in the longer term

The consequences of the cost-of-living shock to households are likely to have a scarring effect on the region’s most badly affected, further exacerbating regional inequality. Forecasts by NIESR (2023) suggest that by the end of 2024, London is projected to have a regional GVA 9 per cent above its pre-pandemic level. By contrast, the Midlands is expected to be 1 per cent below its pre-pandemic level. The post-pandemic crisis poses a significant challenge for policy with levelling up of regions perhaps even more important.

Furthermore, there are additional risks that face the UK economy. Savings accrued for some households and groups in the pandemic are now being run down due to the weathering effect of the cost-of-living crisis. In the medium-term households will have less savings and be less resilient to future shocks, undermining consumer confidence. Compounding the challenge for regional economies there is a risk that low growth becomes a feature of the economy driven by a long period of falling capital investment. Additionally, there is no shortage of further geopolitical risks, from the possible escalation of conflict between Ukraine and Russia to increasing tensions with China related to an increasingly outspoken approach to Taiwan’s independence.

Summary

- Living standards are dropping for most in response to the rising costs of essential goods.

- Low-income households and those living in private rented accommodation or with large mortgages are most vulnerable.

- Wages are falling to keep pace with inflation, particularly in the public sector.

- There is a strong regional component to the cost-of-living crisis with London and the Southeast pulling even further ahead in terms of productivity.

View and download the full REDI Updates report.

This blog was written by Dr Matt Lyons, Research Fellow, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI or the University of Birmingham.