This blog was written by Carol Stanfield from Carol Stanfield Consulting who has co-authored a report for the Productivity Insights Network with Professor Anne Green and George Bramley at City-REDI.

The full report is entitled Evaluation of co-designed programmes for boosting productivity: a follow-up of selected UK Futures Programme projects.

It’s not often you get to conduct a longer-term evaluation of a programme that you worked on in a defunct organisation. But by a series of coincidences, that’s what happened to me. And the findings of the evaluation suggest serendipity has a role to play in tackling the productivity puzzle too.

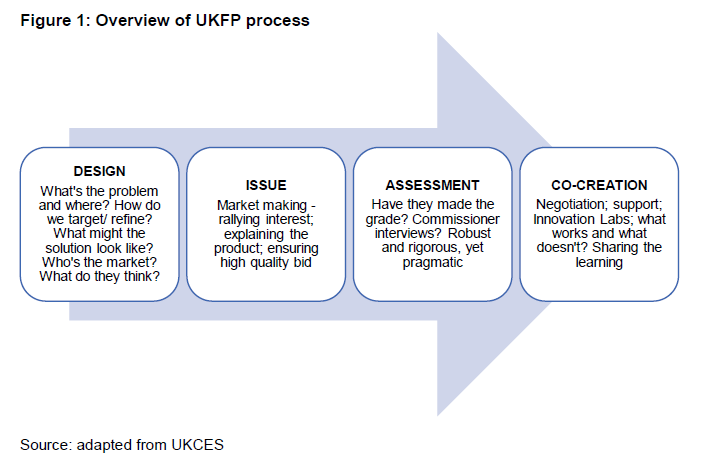

Allow me to explain. I led the UK Futures Programme (UKFP) at the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES) from 2014 to the UKCES’s closure in 2016. UKFP tested innovative ideas with employers to ascertain ‘what works’ in addressing workforce development and productivity problems. In total, £9m of public and private investment went into 32 projects across five so-called ‘productivity challenges’, each focussed on a specific labour market problem hampering productivity and growth, including ‘Progression pathways in the retail and hospitality sectors’ and ‘Developing leadership and entrepreneurial skills in small firms through anchor institutions’. All projects ended in summer 2016, an evaluation report was published, dissemination activities completed – a significant amount of resource, energy and learning put to bed.

Fast forward to May 2018, I attended a Joseph Rowntree Foundation conference and noted that three speakers were talking about projects that had been funded by UKFP. Not as done and dusted as I imagined. Also attending the conference was Professor Anne Green with whom I had worked on research projects previously, and we discussed the potential insight that could be gained from those involved in UKFP in the two years since funding ended to inform productivity policy development. Over the longer-term, what worked, what didn’t and why?

Just a few weeks later, the Productivity Insights Network issued a call for proposals for small research projects which would help fill in evidence gaps in addressing productivity. The funding provided an opportunity to answer the questions Anne and I had discussed and our bid, led by City-REDI at the University of Birmingham, secured funding.

All very fortunate – and very serendipitous – for me!

Indeed, we found that serendipity played a part in the success of the programme too. As one of our interviewees noted about a UKFP initiative.

One of the objectives of UKFP was to engage employers in workforce development and productivity challenges: to persuade them to behave in ways or try things they have not done before. In many of the projects, employers engaged because the product was what they had been looking for at that point in time, though they had not necessarily been proactively seeking support, and it was relatively easy to access.

Of course, serendipity is not particularly helpful from a policy development perspective, but it is an empirical finding. The evidence also suggests fortune favours the brave and persistent and certain factors aided (or their absence hindered) initial and on-going employer engagement:

- Accessible language – from the outset of the UKFP programme that using the notion of ‘productivity’ and productivity metrics can deter rather than attract employers. This was borne out in the follow-up study where the interests of businesses involved in the programme were improving staff retention and leadership development (i.e. positive changes in custom and practice associated with increases in productivity).

- Trusted institutions – for example, local anchor organizations, adopting a relational approach to engagement of individual businesses, proved successful in initiating and maintaining engagement.

- Mutual benefits espoused by peers – a naturally occurring pre-existing relationship/ mutual dependency/ common interests between businesses in a local area facilitated engagement.

- Peer pressure played a key role in keeping businesses engaged in leadership development activities and in maintaining commitment to interventions in the retail and hospitality sector, e.g. through Steering Groups.

- A small amount of funding could go a long way to mitigating risks and covering costs of ongoing business-to business engagement.

- Where this was successful, there was evidence of the development of a ‘localised project ecology’ within which participating businesses in a local area traded with each other.

The evaluation also explored what makes for a successful and sustained project (e.g. a Project Champion, working with organisations that can secure complementary funding streams or can cross-subsidise), and overall, we concluded that maximising the impact of programmes like these requires a number of stars to align:

The evaluation also explored what makes for a successful and sustained project (e.g. a Project Champion, working with organisations that can secure complementary funding streams or can cross-subsidise), and overall, we concluded that maximising the impact of programmes like these requires a number of stars to align:

- The right geography: place is important. There are more likely to be pre-existing relationships with employers and intermediaries within the local area and they can be more easily developed through opportunities to meet face-to-face;

- The right partners: government working with employers and intermediaries that have aligned objectives;

- The right timing: expectations should be realistic, the challenges are deep and complex. In some instances, positive momentum was lost when funding ended, when with additional support, they could have been built upon.

- The right context: a stable policy environment where business can take bold, long-term steps to tackle the issues.

Taking all this together, we suggest these principles could be taken forward in a series of rolling reflective learning projects, with ongoing evaluation and dissemination, operating at a local level and involving organizations with aligned goals. These projects need to be supported strategically by a trusted project champion (in a respected intermediary/ employer organization) working alongside advocates in senior positions in beneficiary organizations who can provide employer leadership. Some resourcing is needed for project managers to deal with implementation and ongoing operational matters of relationship development and maintenance and could also take responsibility for regular reviews of progress against a logic chain demonstrating the potential for impact on enhanced workplace productivity – with continued funding depending on such progress.

Serendipity is important, but it isn’t everything. This evaluation, which I had the good fortune to work on, suggests it can be harnessed by thoughtful policy intervention to tackle the UK’s productivity deficit.

Disclaimer:

The opinions presented here belong to the author rather than the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.