Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates aims to get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WMREDI staff look at the government's flagship policy - Levelling Up. We look at the challenge of implementing, understanding and measuring levelling up Alice Pugh and Professor Anne Green, discuss the challenges that the government will face when trying to ‘level up’ the vast inequalities that exist at regional and sub-regional levels. They also highlight the importance of local institutions when implementing effective place-based interventions. View REDI-Updates.

What is Levelling Up?

When first coming into common usage, there were only vague definitions available of what levelling up meant.

In general, levelling up was seen as a commitment to redressing regional and sub-regional inequalities, so resulting in material improvements to people’s lives. There has been a focus on place and tackling the inequalities of ‘left-behind’ areas of the UK. These are characterised by broad economic underperformance, which manifests itself in low levels of pay and employment, leading to lower living standards. There is a need to level up without compromising growth in already successful places. However, the outcome measures for levelling up need to go further than productivity to include measures related to education, health and crime. Without clarity on how the success of levelling will be measured, local authorities will likely struggle to align national outcomes with local priorities, resulting in a policy disconnect.

Regional inequalities and sub-regional inequalities

There are massive geographical inequalities which have plagued the UK for decades. Since the 1980s, inequalities in productivity, income, employment, education and health have been widening between the best and worst-performing regions. The figure below shows the regional inequalities that exist within the UK on selected indicators. It compares Gross Disposable Household Income (GDHI), GVA per hour worked Healthy Life Expectancy and the percentage of the working-age population (16-64) with qualifications at NVQ3+. The graphs show that London and the South East outperform every other region on almost all of the indicators.

However, variations in performance are not simply a London and South East vs the North issue. Inequalities are stark within regions as well as between them. London may perform well, but there are massive disparities between areas within London. For instance, the average GVA per worker in Wandsworth is £35.15, compared to £60.46 for Tower Hamlets.

Additionally, in 2019, 67% of London’s working population was educated to NVQ3+, compared with other areas, such as the North East, which has 52% of its working-age population with the highest qualifications at this level. However, again disparities are prevalent within regions. For example, in the North West (in 2019) whilst Ribble Valley had 76.6% of its working population educated to NVQ3+, in Burnley this rate was 41.2%. Areas in need of levelling up are often stuck in a ‘low skills equilibrium’, where local employers offer low-skill jobs and operate in low-cost markets, meaning there is little incentive for an unskilled population to upskill. As a result, these areas are also less likely to attract or retain higher-skilled workers too, as they are likely to migrate to where higher-skilled jobs and higher wages are on offer.

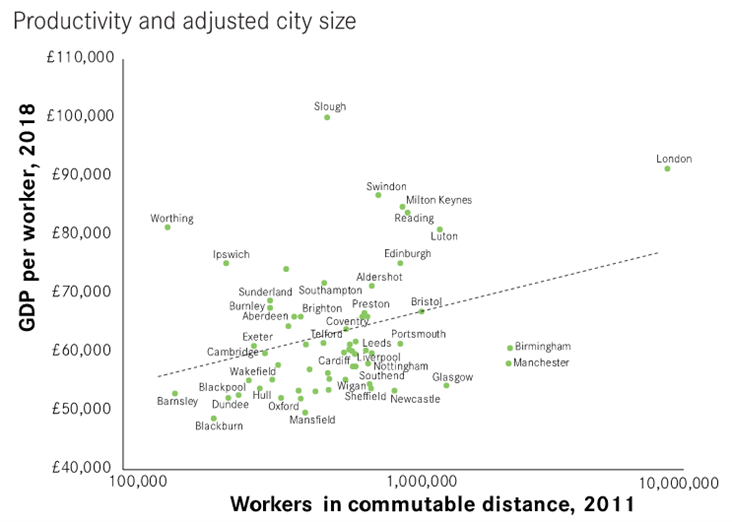

Centre for Cities found that big cities across the UK were considerably below their ‘productivity potential’. The graph below shows that for the eight largest cities outside London, Centre for Cities estimates the productivity gap is £47bn.

Of course, there are non-urban areas that are underperforming too. But improving the productivity gap in these areas would have a very small impact on the wider or regional economy. Centre for Cities estimates that improving the performance of the 76 lagging non-urban authorities across the country would add an estimated £16bn to the national economy; this would be just slightly less than closing the output gap of Manchester alone.

The above regional and sub-regional inequalities are, highly entrenched, and even well-designed policies will likely take many years to produce meaningful impacts. Research by the University of Sheffield found that the UK has one of the highest levels of regional inequality of any OECD country. The research found that one of the most significant reasons for the enormous imbalances within the UK likely stemmed from an over-centralised national governance system. Highly centralised government systems have been found to struggle to tackle place-based inequalities. To tackle place-based inequalities effectively it is recommended that the UK should decentralise greater powers to local government – an approach already undertaken in many other developed nations – or face failing to level up. Decentralisation should be made a key part of the government’s levelling-up agenda.

Subnational governance and short-term funding

However, research carried out by the LIPSIT project, found that the current systems of subnational governance are largely unsuited to the task of levelling up. In recent years, there has been heavy use of funding competitions on placed-based initiatives, creating an extremely inefficient mechanism to deliver placed-based interventions. This is due to the short-term, fragmented and overly specific nature of competitive funding leading to wasteful processes, money not being spent in the places with the most need, an inability to plan for the long-term and strategy failing to be implemented.

There is a complex institutional architecture leading to unclear organisational roles and responsibilities, as well as a lack of local visibility and accountability. Combined these two factors significantly reduce the collective capacity and capability of subnational institutions to make effective change. As well as, hugely undermining the delivery of the UK’s levelling up agenda built on placed-based interventions. The strengthening of subnational institutions, with a commitment to transform central-local relations, is needed.

Brexit

Brexit is expected to impact ‘left behind’ places disproportionately. Research led by the University of Birmingham concluded that the competitiveness of the ‘left-behind’ regions would be negatively impacted by Brexit. The manufacturing sector is one of the most vulnerable sectors to Brexit. The research found the most negatively impacted sectors were most likely to be found in economically weaker areas. The result is widening inequalities as ‘left-behind’ places suffer more from Brexit, compared to more prosperous areas of the UK.

Covid-19

Covid-19 has also contributed to the widening of socio-economic inequalities. During the pandemic, the people most likely to be furloughed or made redundant were those in low-paid jobs, whilst most high earners continued to work. Additionally, as poorer communities are associated with higher rates of pre-existing illness, they were disproportionately vulnerable to Covid-19, resulting in disruptions to work and loss of income. Furthermore, during the pandemic students had unequal levels of access to technology to enable them to engage in meaningful education. This led to a widening of educational inequalities as those with lower access to these technologies (WIFI and internet enable devices) were less able to partake in online education, as a result, their education suffered. This will likely have substantial long-term impact on educational attainment and labour market performance, for students usually deprived areas. Covid-19 has led to a widening of socio-economic inequalities across the UK, increasing the challenge of levelling up going forward

Housing

The housing crisis has been growing for a number of years, with house prices hitting a record high in 2021, driven by undersupply of affordable housing. Shelter estimates that 17.5 million people (22 million including children) do not have access to a safe decent home, that suits their needs and is affordable. PWC research found that 70% of respondents viewed housing as one of the most effective factors for reducing inequality. The shortage of housing has led to a rise in house prices, sustained rises of the relatively insecure private rented sector, declines in home ownership and increased waiting times for social housing. The Centre for Social Justice found that a quarter of the English population find it either ‘fairly or very difficult to pay their housing costs, rising to 43% for private renters.

The inability to be able to afford safe and secure housing affects mental health and physical health. Additionally, owning a house is a vehicle for wealth accumulation, as having a large asset such as a house, provides you with greater access to capital. It is also something to pass on to your children in the future, which will help their financial security. As the housing crisis worsens more and more people in left-behind areas will fall into insecure, expensive and ill-fitting housing. As a result, they will have poorer healthy life expectancy and deteriorating relationships. However, this is a massive task, with research conducted by Heriot-Watt University predicting the UK will need an additional 340,000 per year to keep up with demand, much higher than the government’s current aim of 300,000.

Summary

- Regional and sub-regional inequalities are large and long-established in the UK.

- Big cities perform well below their productivity potential.

- A centralised system coupled with a complex institutional architecture at the sub-national level reduces the capacity for meaningful change at local and regional scales.

- Brexit and Covid-19 have impacted most on those regions and people who are already vulnerable. They also have a differential sectoral impact.

- The housing market is characterised by a shortage of safe, secure and affordable housing overall, which highlights the scale of the challenge faced. The inter-and intra-generational inequalities in access to housing are not conducive to levelling up.

So, levelling up poses a spatial, economic and social challenge. The scale of that challenge is great. Appropriate governance systems, powers, policy mechanisms and capacity are needed to address that challenge – and the precise profile/ nature of the challenge varies across places.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development and Alice Pugh, Policy and Data Analyst at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.