The State of the Region report provides an in-depth look at West Midlands, its past performance, the impact of COVID-19 and Brexit and what the future might hold. The report was developed and supported by the WM REDI partnership to help deepen our knowledge and understanding of the region.

The State of the Region report provides an in-depth look at West Midlands, its past performance, the impact of COVID-19 and Brexit and what the future might hold. The report was developed and supported by the WM REDI partnership to help deepen our knowledge and understanding of the region.

Find out more and download a copy of the State of the Region Report.

In this excerpt from the report, Professor Anne Green talks about the economic geography of the West Midlands, its history, Travel-To-Work Areas (TTWAs) and the impact of COVID-19 on the area.

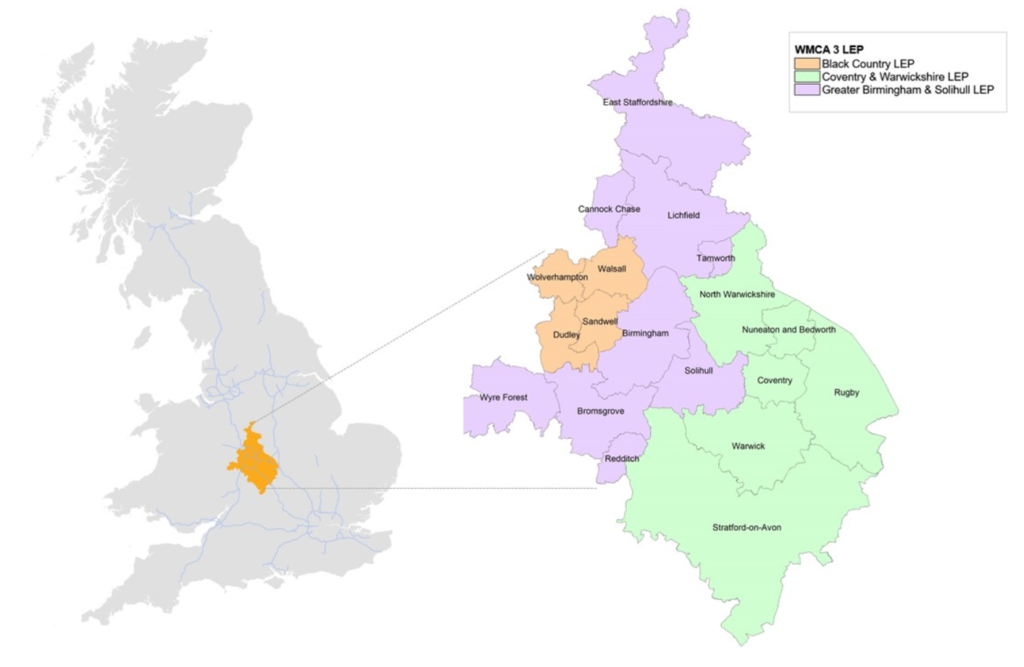

The West Midlands is the only land-locked region in England. It has borders with the North West, East Midlands, South East, South West and Wales. There are no pronounced physical boundaries that would preclude strong economic links with other areas. The 3-LEP area – comprising Greater Birmingham & Solihull, the Black Country and Coventry & Warwickshire – lies at the heart of the West Midlands region in the centre of the country. It is one of the largest urban areas outside London. Its central location at the heart of the road and rail network, together with Birmingham International Airport, means that it is well connected to the rest of the UK and international markets.

The economic history of the 3 LEP

The economic history of the 3 LEP

Historically the 3-LEP area has been dominated by manufacturing, particularly metal goods, metal manufacturing, mechanical and electrical engineering, and car production. This remains important given that evolutionary economic geography indicates that regional and local development is a function of past histories. During the long post World War II boom from 1945 to the early/mid-1970s the West Midlands was one of the most prosperous regions in England, with in-migration from other parts of the country and overseas. Subsequent job losses in the latter part of the 1970s and the 1980s meant that in the geographical imagination the region moved from the ‘affluent south’ to the ‘declining north’. With the decline of the historic manufacturing sectors and the contraction of associated employment, the focus of economic activity in the early 21st century extended outwards from the former industrial heartland areas to the so-called ‘E3I belt’: an arc 20-40 kilometres from the centre of the conurbation to the east and south. This area provides good accessibility, a high-quality environment and increasing employment in a range of innovative manufacturing and business and professional services activities. Birmingham city centre has also emerged as a major centre for business and professional services.

Five travel to work areas

The 3-LEP area represents a coherent functional economic area in its own right, encompassing separable sub-regional functional economic areas. The most commonly used data to delineate functional local areas which are relatively self-contained (i.e. within which a high proportion of residents also work and a high percentage of workers also live) are commuting data from the decennial Census of Population. There are five Travel-To-Work Areas (TTWAs) defined using commuting data from the 2011 Census of Population that broadly map onto the 3-LEP area:

- Birmingham – including Birmingham, Solihull, Redditch, Bromsgrove and Tamworth

- Dudley – including Dudley, Oldbury, Tipton, Wednesbury, Halesowen and Stourbridge

- Wolverhampton & Walsall – including Wolverhampton, Walsall, Cannock and Lichfield

- Coventry – including Coventry, Nuneaton, Bedworth and Rugby

- Leamington Spa – including Warwick, Leamington Spa and Stratford

It is important to note that the commuting flows vary by gender, age, hours of work, mode of travel, occupation and qualification. So males tend to commute further than females, full-time workers further than part-time workers, those in professional occupations further than those in elementary occupations and those with high qualifications further than those with low qualifications. For example, applying the TTWA regionalisation algorithm with commuting data for different qualification groups, across Great Britain there are 153 TTWAs for the highly qualified and 416 for those with low qualifications. To gain further insight into the functional economic geography of the 3-LEP area it is instructive to examine commuting flows for these population sub-groups. Analyses of commuting flows for the highly qualified reveal two large local labour market areas: one encompassing Birmingham and the Black Country, and one covering Coventry and Warwickshire.

This chimes with findings from earlier research indicating that Coventry is to some extent separate from the rest of the city-region and has close functional ties with Warwickshire. There are closer links between Birmingham and the Black Country, together with neighbouring areas of Redditch, Bromsgrove, Cannock, Lichfield and Tamworth. Analyses of commuting flows for the low qualified reveals a pattern more similar to the TTWAs based on aggregate commuting flows, with separate local labour market areas in the south and north of the Black Country, with south Warwickshire distinguished from Coventry and north Warwickshire, and with Redditch and Tamworth emerging separately from Birmingham and Solihull.

This chimes with findings from earlier research indicating that Coventry is to some extent separate from the rest of the city-region and has close functional ties with Warwickshire. There are closer links between Birmingham and the Black Country, together with neighbouring areas of Redditch, Bromsgrove, Cannock, Lichfield and Tamworth. Analyses of commuting flows for the low qualified reveals a pattern more similar to the TTWAs based on aggregate commuting flows, with separate local labour market areas in the south and north of the Black Country, with south Warwickshire distinguished from Coventry and north Warwickshire, and with Redditch and Tamworth emerging separately from Birmingham and Solihull.

Over time the tendency has been for journeys to work to become longer and more complex, so leading to a reduction in the number of TTWAs as large centres expand their influence over time. Given the changing composition of employment, this is unsurprising. There are more professional and managerial jobs commanding higher rates of pay, so enabling more costly travel. A sustained increase in car use for travel-to-work over the long-term enables access to more workplaces in a wider range of geographical locations. The diffusion of some jobs to outer areas is also a factor here. The growth in two-earner households is an additional driver, as it is often not feasible for a household to live within reach of two workplaces. Conversely, part-time workers, low-paid workers and those who have to organise work trips along with trips for other purposes tend to be much more restricted in their travel horizons and tend to be restricted to jobs available in their local area. In such circumstances, spatial mismatches are likely to occur.

The impact of COVID-19

The changes in ways of working in the light of Covid-19 pandemic have implications for the functional economic geography of the West Midlands. From a supply-side perspective, some individuals may work from home more and travel to a workplace less frequently than formerly, perhaps leading to fewer longer journeys if they choose to live in a location further from their workplace. On the other hand, some may choose to live close to their place of work, so as to walk or cycle. Some might have no choice about where to live – and be dependent on opportunities available locally. On the demand-side, it remains to be seen whether city centre working will decline as more people work at home, for at least some of the time. This in turn has implications for the viability of public transport. The functional economic geography of the West Midlands continues to evolve as the purpose of places change … with important implications for competitiveness, inclusiveness and sustainability.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.