What impact has Coronavirus and the lockdown had on homelessness in the UK? Maryna Ramcharan from the West Midlands Combined Authority discusses a paradigm shift in policy dealing with homelessness but notes that we have still not eradicated it completely.

The eviction ban has been extended until 20 September 2020

On 21 August 2020 government extended the ban on private-rented evictions until 20 September meaning no renters will have been evicted for six months. Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick said the Government also intends to give tenants greater protection from eviction over the winter by requiring landlords to provide tenants with six months’ notice of eviction, until at least the end of March. There will be exceptions for tenants involved in anti-social behaviour or domestic abuse. However, the short-term and long-term impacts of these strategies remain unclear. There are also concerns about people in the private rented sector who may build up rent arrears over the coming months and still face eviction when the ban expires.

New cases of homelessness have been reported

The National Housing Federation reported that an increase in homelessness has already been identified and these newly homeless people will also need accommodation because of the crisis. Issues such as youth homelessness, increased incidences of domestic abuse, hospital discharges, and prison releases are likely to become more problematic.

Has COVID-19 nearly ended homelessness?

COVID-19, and the policy response to it, undoubtedly caused a paradigm shift in the homelessness system. It has shown that where the political will exists, it is possible to eliminate rough sleeping. But we should be cautious about any claims that COVID-19 has solved the issue of homelessness, says Margery Infield, NPC.

The majority of people who are homeless in the UK do not sleep rough. Last year, around 120,000 households became homeless in England, including nearly 50,000 children. Most of these people can be described as ‘hidden homeless’, living in temporary accommodation (such as council-provided B&Bs) or ad hoc shelter (such as sofa-surfing).

The best estimates suggest that people sleeping rough make up less than 5% of all people who are homeless. Therefore, merely providing shelter to those sleeping rough will have a limited impact on the wider issue of homelessness.

It is also crucial to prevent people become newly homeless as a result of COVID-19. PSE research showed that poverty is the largest risk factor for homelessness which has been exacerbated by impacts of COVID-19 – 64% of those in serious financial difficulties are renting, and 31% are homeowners. This suggests that the coming recession will result in more people losing their permanent homes.

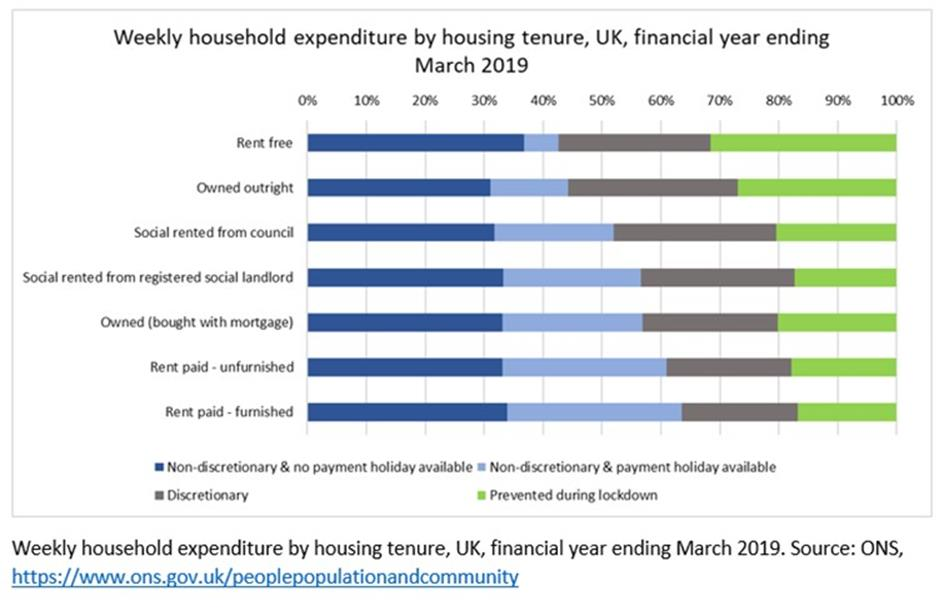

As recent ONS analysis shows, renting households spend 61% of their usual weekly budget on essentials, compared with 52% for households who own their home outright or with a mortgage. This is largely driven by housing costs, which account for 28% of budgets for renting households and 21% for homeowners (below).

According to a survey by the Resolution Foundation, renters are more likely than homeowners to have fallen behind with their housing payments during the lockdown. They have been less likely to receive a payment holiday on their rent, as opposed to those with a mortgage. Spending on activities including holidays and eating out is proportionally lower among renters, potentially limiting their ability to manage housing costs alongside a loss of income.

This blog was written by Maryna Ramcharan from the West Midlands Combined Authority.

Disclaimer:

The opinions presented here belong to the author rather than the University of Birmingham.