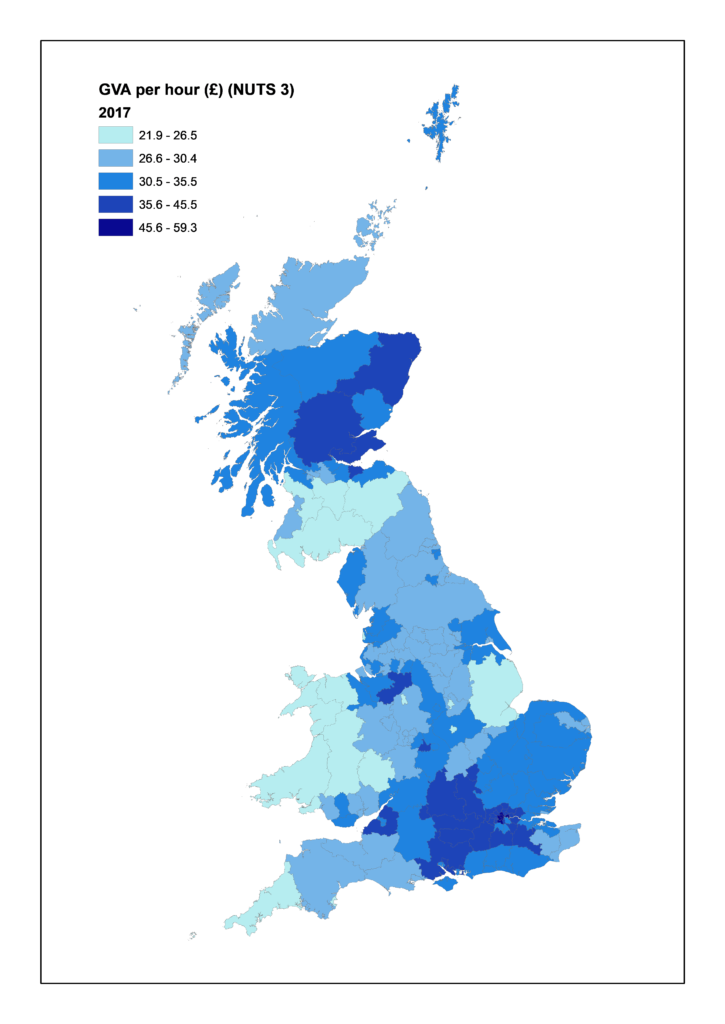

Over the past decade, the gap between the UK’s productivity performance and other OECD countries has been widening. This is due to unusually slow growth rates in UK productivity since 2010 in spite of rising employment, leading to what has been termed the UK’s ‘productivity puzzle’. Within the UK, there are also vast variations in productivity between regions. These are shown in the map below using gross value added (GVA) per hour data, the most commonly used measure for comparing productivity within and across countries. Here it is shown in its nominal form for 2017 for NUTS3 regions in Great Britain (GB).

From this map, we can clearly see the productivity differentials between GB regions, with London, most of the South East and a small number of large cities in England and Scotland showing as having the highest productivity in terms of regional outputs.

But why are there such vast variations? The answer, of course, is not a simple one and the UK’s productivity puzzle in large part remains unsolved. There are, however, a wide range of studies by leading productivity experts that point to a number of key factors associated with national and regional productivity performance and variations as outlined below.

Knowledge and Innovation

Regional productivity performance has been linked to investment in R&D and other innovation activities (Cozza et al., 2012; Vieira et al., 2011); knowledge assets (including both human and technological) (Paci and Marrocu, 2013); and human capital, patenting activity and entrepreneurship (van Oort and Bosma, 2013).

FDI, Capital and Technology

Research finds that foreign-owned firms contribute more to productivity growth than UK-owned firms (Harris and Moffat, 2013). Research also suggests that productivity is driven by capital accumulation and technological and digital diffusion, with technology gaps a source of unused potential productivity growth (Filippetti and Peyrache, 2013).

Connectivity and Infrastructure

Places with poor quality transport are disadvantaged in comparison to places with better quality transport (Banister and Berechman, 2001). Linking to this evidence suggests that accessibility improvements can lead to places attracting more firms (Gibbons et al., 2010). Access to cities has also been found as influential (Rice and Venables, 2004) due to the benefit of high jobs density for knowledge sharing and new learning.

Industry

Industry

Productivity varies considerably by industry with, for example, financial services and manufacturing being relatively productive sectors in comparison to construction and retail that have productivity levels below the national average (Oxford Economics, 2018). The drivers of productivity between sectors also vary, with diversity found as having a positive effect on the performance of knowledge-intensive services in ‘old’ European urban areas whilst specialization is effective in ‘new’ low-tech manufacturing urban areas (Marrocu et al., 2012).

Skills

Different levels of skills between regions is another key factor for the differences in local economic performance linked to productivity. Regions with high proportions of level 4 skills have been found as having higher productivity levels (Oguz and Knight, 2011), although productivity has also been linked to job-related training as well as low and medium skills (Abreu, 2018). Emerging technologies such as AI could radically and rapidly change the nature of skills needed (Besleu et al., 2018).

Inclusivity, Inequality and Wellbeing

Inequality, wellbeing and inclusivity have been linked to productivity, with research finding that efforts to improve educational outcomes, reduce welfare dependency and tackle debt and addiction are likely to generate productivity gains (Centre for Social Justice, 2018). Lower happiness has also been associated with lower productivity (Oswald et al., 2015). It has been suggested that strategies that focus both on productivity growth and inclusion are likely to have the greatest impact on living standards (Stansbury and Summers, 2017).

Governance and Institutions

Cities with fragmented governance structures tend to have lower levels of productivity (Ahrend et al., 2014). This is because regional institutions are critical to delivering on policy relating to productivity and its drivers (Cook et al., 2018). This calls for a stable, properly resourced, long-term policy framework to help improve the fortunes of struggling cities (Martin et al., 2017). A positive relationship has also been found between public-private partnership investments and productivity (Navarro-Espigares and Martin-Segura, 2010).

The central aim of the LIPSIT project is to identify institutional and organisational arrangements at the regional level that tend to lead to the ‘good’ management of policy trade-offs associated with increasing productivity and to make recommendations based on this.

This blog was written by Charlotte Hoole, Research Fellow, City-REDI, University of Birmingham and was first posted on the LIPSIT project website.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.