In this blog, Peter Kenway, Director for the New Policy Institute discusses their new report looking at the state of economic justice in Birmingham and the Black Country.

NPI’s new report on economic justice, published by the Barrow Cadbury Trust, assembles the statistics to tell a story that people who live in Birmingham and the Black Country know all too well, about poverty and deprivation and one of the weakest local economies – in the Black Country – that 50 years ago was England’s economic heartland.

If this story is known, why tell it again in this way? There are three reasons.

First, the report underlines the point that Britain’s problems cannot be reduced, even roughly, to a North-South divide.

England’s second city and its four Black County neighbours, home to more than two million people, have the unhappy distinction of having a bigger share of its population experiencing poverty and deprivation than anywhere else this large.

Locally elected representatives, whether serving at the local, regional or national level, need be in no doubt that policies directed at relieving poverty, exclusion, inequality and ill-health are every bit as important here as anywhere.

Nor is this social security spending just “welfare”. When looking at it through an economic lens, as this report does, money going into pockets and purses is money going into the economy, its local shops and services, etc.

Second, the report demonstrates that ‘levelling up’ is not just a national requirement from south to north or the midlands but within each of these areas too.

This is well-illustrated by the Black Country – economically the weakest of England’s 38 Local Enterprise Partnership areas. Yet the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA), of which it is a part, has had the fastest growth of combined authorities.

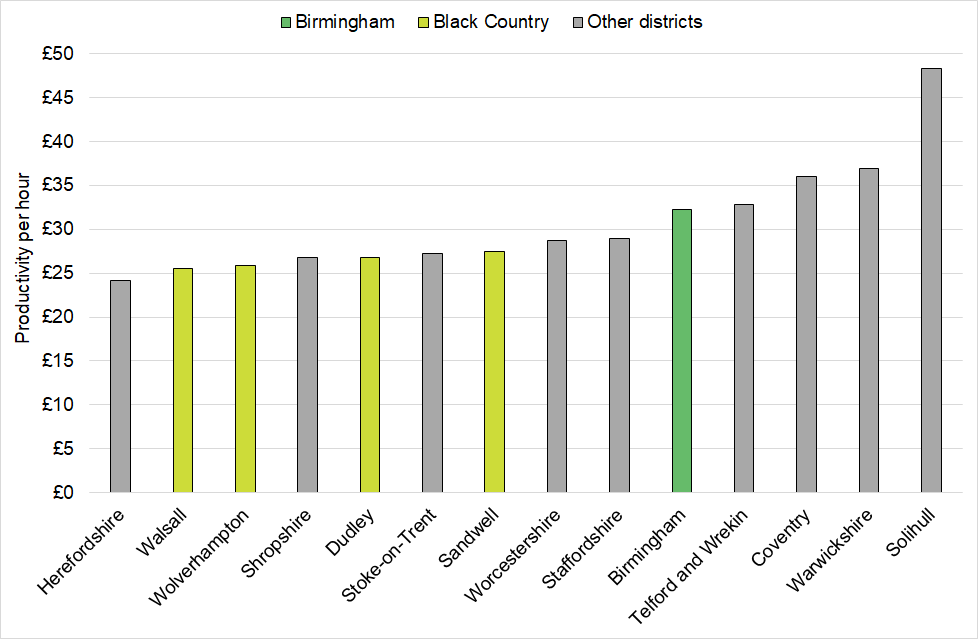

What is driving the WMCA is the eastern part – Coventry and Solihull – which are both economically strong in themselves and also part of a wider centre of growth across Warwickshire and beyond. The 14 metropolitan and unitary districts and counties are shown in the graph are actually arranged according to the average level of productivity per hour. But the graph would look little different if they were arranged west to east.

Over the last decade, these economic disparities between the stronger and weaker parts of the WMCA have grown rather than shrunk.

Just because the WMCA is doing well does not necessarily mean that all parts of it are. The Black Country needs special attention.

Third, the report is trying to extend attention beyond the normal focus on the ‘economy’ of a place, to the economic contributions made by, and the economic rewards returning to, the people who live and work in the place.

For Birmingham, which draws more than a third of its workforce from outside the city, that means recognising that what is good for the economy does not benefit its residents to the same extent. For the Black Country, it means recognising that its economy, which is heavily dependent on local residents for its workforce, is limited to an unusual extent by their level of skills.

This is something that ties Birmingham and the Black Country together, namely, that too high a proportion of working-age residents in both places have too few qualifications and (by inference given the lack of direct evidence) too few skills too.

The report suggests that just because Birmingham and the Black Country have coped so far, the path followed after 2008 may no longer be sustainable. The economic changes which the pandemic has sped up (threatening employment in retail and financial services plus the acute need for a larger, high-quality care sector), coupled with the challenge of adapting to a zero-carbon economy (threatening old, low value-added manufacturing, plus the need to retrofit the housing stock) will not be realised without a much better-qualified workforce. There will not bring economic justice unless the fruits of the healthier, more productive economy flow to the residents and workers, through earnings and pubic services.

In its young population, Birmingham and the Black Country have a wonderful potential advantage. The question now is whether that potential can be realised.

This blog was written by Peter Kenway, Director for the National Policy Institute.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.