Anne Green discusses recent changes to international migration and its impact on the UK labour market. This blog is part of a series looking at the UK Labour Market. See also: - Why are the Over-50s Leaving the Workforce? Labour Market Flows and Future Participation Flows - How do Fertility Rates and Childcare Costs Play out in the UK Labour Market? - What Are the Current Challenges in the UK Labour Market and How Can They Be Addressed? - Changing Labour Market Participation of People Aged 50 Years and Over

The role of international migration in the UK labour market

Immigration is a key economic and social issue: it has fuelled economic growth and prosperity, changed the demographic composition of the UK and shaped much of the political agenda. Many of the UK’s labour and skills needs have been met by international migration. This is because employment of workers from outside the UK is one possible strategic and tactical response to address labour and skills shortages. As noted in a review commissioned by the Migration Advisory Committee on Employer decision-making around skill shortages, employee shortages and migration and outlined in a previous City-REDI blog on Changes to the UK Immigration System After the Brexit Transition Period, it is a means of making numerical adjustments to, and changing the quality of, labour supply.

Attracting international migrants has been an important way in which the government and employers have sought to meet labour and skills needs in the UK economy for many years. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the Commonwealth was a key source of incoming labour. More recently – at least until Brexit – the European Union (EU) has been a major source of international migrants to the UK.

The size and composition of flows are influenced by immigration policies. Immigration policies in both the UK and other countries matter because they influence the relative attractiveness of alternative destinations.

Recent trends in international migration to the UK

The Migration Observatory notes that net migration is a commonly used measure of the overall scale of migration in the UK. This measure takes account of those moving to the UK and those leaving.

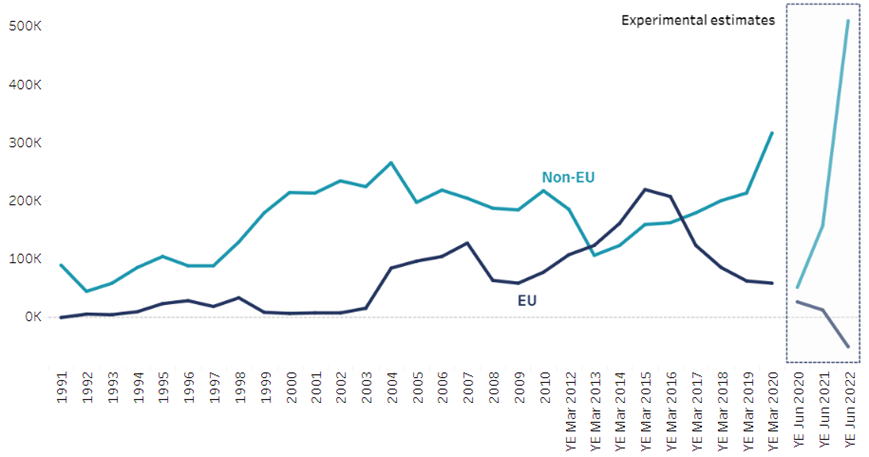

In recent years net migration has been impacted by Brexit (and associated changes in the UK immigration system) and the Covid-19 pandemic and restrictions on international mobility. According to the Office for National Statistics, total net migration was at a high level of 504,000 in the year ending June 2022, with the opening of new routes for Ukrainians and Hong Kong British Nationals (Overseas) status holders being key factors here. Other factors in the increase were an increase in international students, which likely is a function of the strategy of increasing and diversifying foreign student recruitment and the reintroduction of post-study work rights post-Brexit. A further factor in the increase was skilled workers on work visas; here the health and care sector played a primary role in driving the increase.

Over the most recent years, the increase in overall net migration has been driven by non-EU migration (as shown in the Figure below). By contrast, EU net migration decreased sharply from 2016 onwards and thereafter remained low. Between March 2016 and March 2020 EU net migration fell by 58%. This aggregate figure disguises a 126% fall for EU-8 migrants (from Eastern and Central Europe), compared with 40% for EU-2 migrants (from Bulgaria and Romania) and 42% for EU-14 migrants (from the longer-standing EU member countries in western Europe).

Estimates of net migration and immigration of EU and non-EU citizens in the UK per year, 1991 to year ending June 2022

Changing migrant stocks

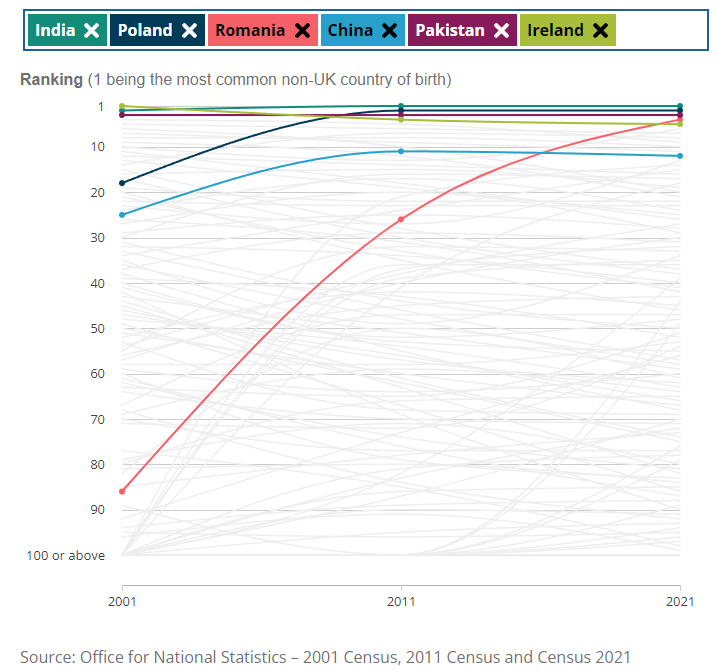

The recent publication of the 2021 Census of Population data provides a longer-term view of the changing stocks of people born outside the UK according to selected country of birth. India accounts for the largest single number in 2021, followed by Poland, Pakistan, Romania and Ireland. Eastern European countries such as Poland and Romania have risen up the rankings over the 20-year period (as shown in the Figure below), largely reflecting immigration to the UK after their accession to the EU.

Changing rank of selected non-UK countries of birth, 2001, 2011 and 2021, England and Wales

Hence changing immigration rules, alongside historical links, geographical proximity and size of the source country play a role here.

UK immigration policy

Prior to Brexit EU citizens coming to work in the UK were eligible to take up employment in any job. As an EU member state, the UK was unable to use any kind of visa system to control migration from other EU member states except in very particular circumstances; (following the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the EU in 2007, the UK limited opportunities for Bulgarians and Romanians to work in the UK). By contrast, citizens of countries outside the EU were subject to immigration control and did not have the right to enter the UK to work without a visa.

From 1st January 2021, the UK has had a new immigration system. Free movement arrangements for European Economic Area (EEA) nationals have been revoked. There is now a single skills-based system for all migrants to the UK that makes no distinction on the basis of nationality; (Irish citizens are a special case here under the provisions of the Common Travel Area where there are reciprocal rights for UK and Irish citizens). Migrants coming to work in the UK need to be sponsored by an employer and work in at least a middle-skilled job paying a wage equal to or above a minimum salary threshold. There is no provision for migration to low-skilled jobs except on a temporary basis.

In comparison with the previous Points Based Immigration System (PBS) the current skills-based system has been expanded to include middle-level skills and has a lower salary threshold. This means that the current UK immigration system is less liberal for EU workers and more liberal for non-EU workers than the one that preceded it. Some of the key immigration routes are outlined below.

To work in the UK under the ‘Skilled Worker route’ individuals require 70 points under the PBS. Some of these points are non-tradeable (i.e. every individual needs to meet them): (1) a job offer from an approved sponsor; (2) a job offer at the required skill level (i.e. Regulated Qualifications Framework [RQF] 3): A level or equivalent); and (3) ability to speak English at a required level. Together these make 50 points. The additional 20 points required can be attained by earning a salary that equals or exceeds the general salary threshold of £25,600 (£10.10 per hour) or the going rate for the occupation (whichever is highest). If this salary threshold is not met there is scope to earn extra points (provided a lower minimum salary threshold is met) by having a job offer in a specified shortage occupation (i.e. designated by the Migration Advisory Committee as being on the Shortage Occupation List [SOL]) or a PhD relevant to the job. Within the Skilled Worker route, there are exemptions to some of the above requirements for those on a Health and Care visa.

There is also a ‘Graduate route’ which allows international graduates who have been awarded their degree from a UK university to stay in the UK and work or look for work, at any skill level for at least two years. For those with a PhD or other doctoral qualification, the visa will last for 3 years. The Graduate route is unsponsored – i.e. applicants do not need a job offer to apply to the route. There is no minimum salary requirement and there are no caps on numbers. Graduates on the route can work flexibly and switch jobs. After two years a switch to the Skilled Worker route is possible providing that the conditions of that route are met. International student visas are currently the subject of much political debate, with indications existing that the government may seek to place new restrictions on international student visas. Universities have argued that international students bring substantial economic and other benefits.

The intra-company transfer (ICT) route allows multinational organisations to facilitate temporary moves into the UK for key business personnel through their subsidiary branches, subject to ICT sponsorship requirements being met. The route requires applicants to be in roles skilled to RQF 6 (graduate level equivalent). There is a different minimum salary threshold from the main Skilled Worker route.

From the outset of discussions on post Brexit immigration policy, the Government confirmed that it would not implement a route for low-wage workers (i.e. those requiring only short-term training). It cited instead the need to invest in staff retention, productivity and automation, rather than rely on migrant workers. This means that sectors and occupations particularly reliant formerly on EU migrant-free movers to fill jobs which do not require high and medium skills levels have been hit particularly hard by changes in immigration policy. The industries most affected by these changes are estimated to be wholesale and retail trade along with public administration, education and health.

Immigration policies in other countries – and why they are important

The UK competes for skilled labour with other countries. In this regard, the costs of using the skilled worker visa system is emerging as a key challenge. In the UK there is an application fee for a skilled worker visa (which varies according to whether an application is made from within or outside the UK, whether the job is on the Shortage Occupation List, the length of time in the UK, etc.) and an annual health service charge. An individual also needs to demonstrate that they can support themselves by showing that they have a certain amount of money in a bank account.

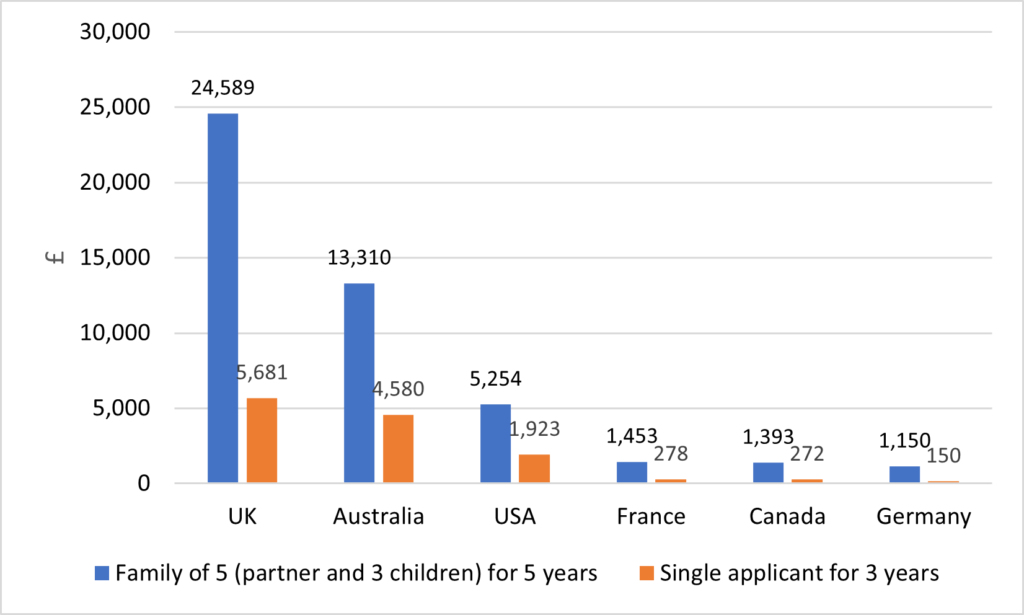

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Migration Inquiry in 2021 on The Impact of the New Immigration Rules on Employers in the UK estimated comparative costs for skilled workers. The much higher costs in the UK than in various competing destinations are immediately apparent in the Figure below.

Visa fee comparison, 2021

Alongside these lower costs, the Recruitment & Employment Confederation highlights that countries such as Canada and Germany are active in targeting immigrants to fill skill shortage occupations. Immigration and Skills Canada has implemented a Global Skills Strategy to support businesses in attracting foreign talent through simplification of the administrative process. Measures include shorter processing times for applications and exemptions from the acquisition of work permits to skilled workers most in demand. In Germany, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs has sought to attract skilled workers by offering vocational training qualifications – including learning German in order to ease integration into German society.

So, in terms solely of costs, the UK appears as a relatively unattractive destination vis-à-vis competitors.

Employers and the new skills-based immigration system

Qualitative research conducted by the MAC between November 2000 and May 2021 focusing on employer experiences of skills shortages and migration across three sectors – construction, manufacturing and IT – highlighted that both the Covid-19 pandemic and changes to the immigration system in 2021 had a major impact on businesses and international migration. However, the Covid-19 pandemic tended to be viewed as a short-term threat that would be overcome in the long-term, while the ending of free movement was viewed more as an ongoing threat. The research highlighted concerns about the costs of using the skilled worker visa route, particularly for workers in medium-skilled roles. Other challenges included the English language requirement in some instances where workers otherwise meet skills requirements, difficulty in meeting the earnings threshold (especially outside London and the South East), and that the immigration system no longer caters for employers who require flexible labour to undertake short-term tasks; previously EU nationals could come to the UK for short periods to undertake particular tasks.

Reflecting how the immigration system has implications for the numbers and composition of migrant flows, it appears that the post-Brexit immigration system has substantially reduced work migration from the EU. By contrast, in the second quarter of 2021, non-EU citizens’ demand for work visas had returned to numbers relatively close to pre-pandemic levels, after a decline during the Covid-19 pandemic. At the end of 2022 the MAC reported that up to 2022 quarter 2, EEA nationals made up around 7% of the cumulative total of skilled worker visa applications.

Looking ahead

International migration is one potential means of increasing the supply of labour in the UK. Importantly, migrants are typically younger than the UK population overall and if in work they generally lower the average age of the workforce. Analysis by the ONS of all people arriving in England and Wales in the year before the 2021 Census shows that their median age was 26 years, compared with 40 years for the overall population. In turn, this younger age profile of migrants has implications for fertility rates and so for the demographic structure of the UK.

The extent to which employers turn to international migration as opposed to other alternatives to address labour and skills shortages depends in part on the relative ease and costs incurred in complying with the immigration system. Likewise, potential immigrants may choose to go to alternative destinations. The relative attractiveness of the UK matters.

This blog was written by Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.