Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates aims to get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WMREDI staff look at the government's flagship policy - Levelling Up. We look at the challenge of implementing, understanding and measuring Levelling Up. Professor Raquel Ortega-Argiles discusses regional imbalances in the UK, the impact of Brexit and Covid and the need to act upon regional inequalities. View REDI-Updates.

The City-REDI contribution to the ESRC Rebuilding Macroeconomics Network initiative on The Long-Run Consequences of Adverse Economic Shocks: UK Regional and Urban Inequalities were featured in the White Paper sub-section ‘The Role of Public Policy’ (pp. 99) and the sub-section considering “the appropriate role of public policy in reshaping the economic geography and reversing spatial disparities across the UK” makes use of our data in Figure 1.70.

Other City-REDI work provides further nuances to the White Paper’s arguments as to why a long time frame and also international comparators are so important. If policies are ill-conceived and poorly applied, the boost to potential output in left-behind places could prove to be temporary rather than permanent. This is precisely why it is so important to analyse inter-regional inequalities and how they relate to growth prospects from a historical perspective and to look at best practices from international cases that successfully have been able to use policy initiatives to improve socio-economic cohesion.

Historical inter-regional inequality disparities – a European comparison

In a historical and international comparative context, our research explores the nature and scale of inter-regional and inter-urban inequalities in the UK and identifies which inequalities are linked with national levels of economic performance. We consider the UK-specific experience of the relationship between interregional inequality and economic growth in the light of international comparisons using over a century of evidence, and in more detail over the last two decades. We demonstrate that the UK-specific relationships between (extremely high) inter-regional inequalities and national economic growth are an outlier by international standards.

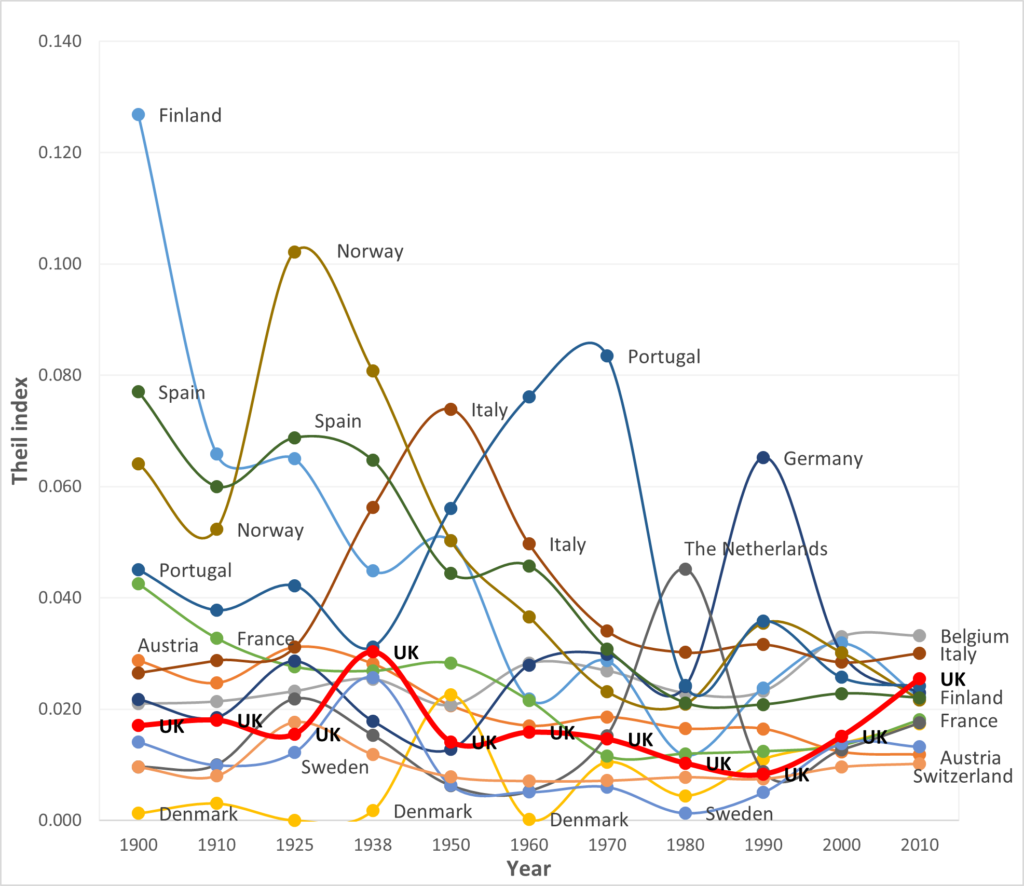

The Levelling Up White Paper (Figure 1.24) shows that UK inter-regional inequalities have widened and narrowed and then narrowed again over the last century. To situate the scale of these differences in the context of the experience of other industrialised countries, Figure 1 applies a spatial Theil Index to data on economic development (Roses, J.R. and Wolf, N. (eds) (2019), The Economic Development of Europe’s Regions: A Quantitative History Since 1900, Abingdon: Routledge.) to plot the long-run evolution of interregional inequality in GDP per capita across a range of western European countries over more than a century. Cross-country productivity differentials between European countries were very large in the earlier years of the twentieth century. Inter-regional disparities greatly narrowed in most countries, including the UK, following international and inter-regional convergence processes during the second half of the twentieth century. After 1990, the UK displays an opposite trajectory from the other European countries, showing a profound increase in inter-regional productivity variations.

The relationship between inter-regional inequality and economic growth

As the Levelling Up White Paper indicates, it is possible that policies that support left-behind places could boost not only the level of activity but also the underlying growth rate. This would significantly boost the net present value of local growth policy. The document emphasises that there is little evidence that regional policies come at the expense of reduced aggregate economic growth. If anything, as our research demonstrates, the evidence suggests large spatial disparities hamper economic growth.

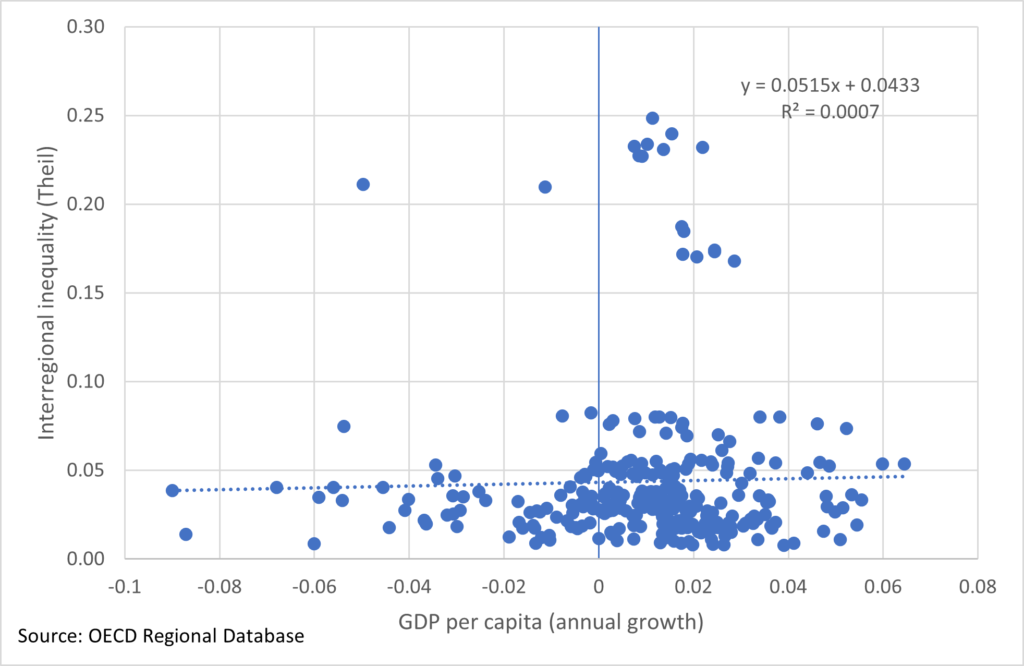

Our OECD-wide analysis of the relationships between economic growth and interregional inequality shows that such relationships are fragile. The only clear evidence of a positive relationship is in the post-2008 crisis period, a result that points to differentials in regional resilience rather than inequality-led growth. Moreover, when former transition economies are removed from the sample (see Figure 2), the positive relationship between inter-regional inequality and national annual economic growth disappears. Hence, the international evidence suggests that the UK’s very high spatial inequalities have hampered, rather than facilitated, national economic growth.

As the Levelling Up White Paper indicates, high UK spatial disparities are likely to have hampered growth and well-being not just in left-behind places but across the UK as a whole. The dividend from unlocking this potential is likely to be large, both in financial (such as productivity) and non-financial (well-being, health, skills) terms. It is also likely to be lasting. Closing geographic imbalances thereby potentially deliver a twin-win, boosting living standards and life satisfaction, durably and significantly, in both left-behind and steaming-ahead places (see page 99).

Reflections

These economic arguments underpin wider socio-economic and political economy arguments for Levelling Up. The UK economy has become so highly unbalanced that the UK is now one of the world’s most inter-regionally unequal countries (McCann 2016). Over the last forty years, economic growth has been heavily concentrated in and around London and its hinterland. While this has been partly due to economic mechanisms, it has also been in part the result of numerous national governance and institutional decisions, taken without any real consideration of their long-term spatial consequences. The enormous productivity imbalances we now see across the UK underpin significant inter-regional variations in prosperity, wellbeing and quality of life to the extent that the country is becoming largely decoupled into regions with predominantly prosperous towns and cities co-existing alongside regions of mostly broken towns and cities. These profound differences are becoming ever more difficult for governments to respond to and ameliorate, and this failure puts enormous strains on the efficacy of our governance systems and the trust which people have in them, giving rise to a marked ‘geography of discontent.

More recently, the notions of “levelling up” and “rebalancing” are intrinsically related to two recent shocks: Brexit and Covid-19, but this was not always the case, as the inequalities long pre-date these events.

In terms of Brexit, almost all the available evidence suggested that the less prosperous regions are the ones that are going to be more heavily affected by the Brexit trade-related consequences (See this research project and these papers Thissen, M; et al (2020), Billing, C., et al (2020) and Chen, W., et al (2018)). This evidence also shows that Brexit effects will make regional inequalities greater than they already were.

The Covid-19 pandemic already has and will continue to have profound impacts worldwide (McCann, P., et al (2021) and Bailey, B., et al (2020)). The real long-term implications of the pandemic will only begin to become evident in the coming years. Regions specialising in tourism, hospitality, entertainment and transportation services will be especially hard hit, as will many retail centres. The ongoing pandemic shocks to these regions may lead to severe long-term economic scarring and will set some of these regions into downward growth trajectories for the foreseeable future. Although many prosperous and densely populated regions have suffered some of the most severe localised Covid-19 outbreaks, there are also strong arguments to suggest that the general long-term pattern will be that the economically weaker regions are likely to suffer the most from Covid-19 (McCann, P. and Ortega-Argiles, R. (2021)). As we move towards a post-Brexit and post-pandemic context, addressing these inequalities will be even more important.

This blog was written by Raquel Ortega-Argiles, Professor of Regional Economic Development, Alliance Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.