Abigail Taylor looks at trends that might impact the future of work and training and what this could mean for the West Midlands. This article is part of larger project looking at Megatrends in the West Midlands. Megatrends are major movements or patterns or trends that are having a transformative impact on business, economy, society, cultures and personal lives. The project examines some of these megatrends in a series of provocations, podcasts and a report. View the full provocation.

This article is a summary version of a slightly longer paper prepared in early 2021 for a project on Megatrends and Future Cities, which is also informing a Future Business District Study. It is concerned with trends in the future of work and training and their implications for the West Midlands. Increasing technological innovation and growing adoption of new technologies is changing the types of jobs available and the range of skills required by employers. At the same time, participation in training is declining. The Covid-19 pandemic risks accelerating and accentuating these trends, further polarising labour markets and widening inequalities .

As the Futures of Work blog puts it “By compressing processes already underway, the pandemic has expedited the future of work into the present”.

Introduction

Work in the future is likely to involve greater demand for higher-level skills, especially technology and interpersonal/people skills. Unless the UK finds a way to radically upskill its workforce, over the next decade, this will lead to skills mismatches limiting individual employment and earnings opportunities and also firm performance and productivity, so reducing UK competitiveness. Reskilling and upskilling the workforce is urgent. Unless the UK finds a way to radically upskill its workforce, over the next decade, this will lead to skills mismatches which could limit both individual employment and earnings opportunities but also firm performance and productivity.

By investing in training, firms can build on existing talent and prepare themselves for the changing labour market. Developing the quality of managers and a broader institutional culture which champions training is essential to this.

Key policy messages

- Reskilling and upskilling the UK workforce is urgent to avoid significant skills gaps and mismatches within the next decade.

- Developing training and improving the quality of managers is important if firms are to maximise the benefits of increased technological capability.

- There is a need for employers to work with government, education providers and job search platforms to improve data regarding job and skills opportunities for workers.

- There is a need to work across organisations to share good practice for developing the quality of managers and a broader institutional culture which champions training. It is vital such initiatives are actively led from the top of organisations.

- Firms need to work with skills providers to develop opportunities for school and university students and leavers who have faced two years of disrupted education. Strategic partnerships are essential to preventing a spiral of decline.

Major trends and issues

Employer surveys have identified key skills gaps within the existing workforce, including time management, leadership skills, customer skills, analytical skills and digital skills. In the 2019 Employer Skills Survey, 32% of employers cited being unable to recruit specific skills as the main cause of skills gaps compared to 25% in 2015. Interviews conducted with employers in 2019 identified how employers increasingly value staff who possess a mix of social and behavioural skills.

While employers have indicated that the existing skills gaps are already causing issues in terms of firm performance, participation in training is also declining, UK employers stand out internationally for their preference to recruit rather than train and employer investment in training in the UK is low relative to that in many international competitor countries. The average volume of training in the UK has declined over recent decades. For example, the average time spent on job-related training over a four-week period declined by 10% from 2011-2018 according to the Labour Force Survey whilst the annual volume of formal training in the UK Household Longitudinal Study fell by 19 % over the period 2011 and 2017.

This lack of training provided by employers is compounded by trends relating to employee participation in training. The low skilled, poorly paid, young and lower qualified are the least likely to undertake training. In the 2017 Adult Participation in Learning Survey, full-time staff were “significantly more likely” to learn for work or career-related reasons than those who worked part-time or were self-employed. In the 2019 Survey, whilst social grade continued to be the most common factor predicting whether an adult would participate in training, participation among those in higher social grades and with higher levels of education also fell. The 2019 survey identifies particular concerns regarding a continued decline in training participation among working-age adults.

While the UK population is gradually becoming more qualified, demand for higher qualifications is expected to outstrip the rise in the proportion of the population with degree level qualifications or above. Advances in technology such as automation and big data mean that 7.4% of jobs in England are at high risk of some of their duties and tasks being automated in the future. By 2030, there could be a 13% increase in jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree, and 7 million additional workers could find themselves under-skilled compared to the requirements of their job.

The pandemic had an immediate impact on the demands of firms and their workers, with the increased adoption of new digital technologies among firms. In the period from late March to late July 2020, over 60% of firms adopted new digital technologies and management practices; and around a third invested in new digital capabilities. This digitalisation of work requires an urgent process of training and upskilling staff: the Industrial Strategy Council suggests that this most important of skills is expected to experience the highest level of under-skilling by 2030 if existing trends continue (see here and here).

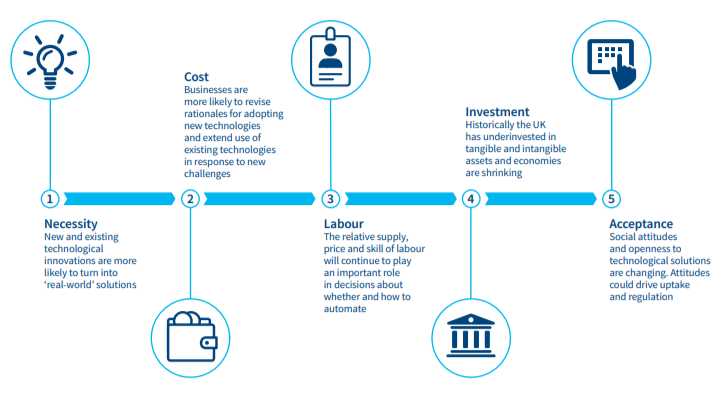

Covid-19 could accelerate automation in five ways: necessity, cost, labour, investment and acceptance, as demonstrated in the Figure below showing the extent, nature and pace of technological adoption. The role that automation will play for skills will be to replace lower-skilled jobs, requiring reskilling and upskilling of workers if they are to remain in the labour market.

The existing gaps in skills required by employers combined with the current underfunding of training, the inequalities in access to training, and likely continued increases in demand for highly skilled workers clearly demonstrate the urgent need for reskilling and upskilling of the workforce. As the Industrial Strategy Council has argued, employees with a range of social and emotional skills, analytical and interpretative skills, and digital skills will be better placed to adapt to changing job requirements in the eyes of employers.

What might the future look like?

The existing analysis provides insight into how continued growth in automation and AI may impact skills demand over future decades.

Modelling by McKinsey suggests that by 2030 skills shortages are likely to be more severe in terms of ‘workplace skills’ than ‘qualifications’ and ‘knowledge’ and that the most widespread under-skilling is predicted to be in basic digital skills. In line with advances in technology, ‘basic digital’ skills by this point, are likely to be increasingly advanced compared to skills considered ‘basic’ today. Predictions suggest 5 million workers could be acutely under-skilled in basic digital skills by 2030 whilst up to two-thirds of the workforce might face some level of under-skilling.

Other skills in which employers are likely to face acute skills shortages include core management, STEM and teaching and training skills. The analysis suggests that 2.1 million workers are likely to suffer from acute under-skilling in at least one core management skill (leadership, decision-making or advanced communication), whilst 1.5 million workers are likely to face acute under-skilling in at least one STEM workplace skill and 800,000 workers are likely to face acute under-skilling in teaching and training skills which are vital upskilling others.

Some sectors and occupations are likely to be harder hit by the impact of automation than others. It is likely that across Europe, occupational categories such as STEM professionals and healthcare workers will grow significantly, whilst declines are predicted in relation to the number of office support and production jobs. For example, predicted changes in human and health services mean that by 2025 technology will replace many repetitive tasks such as data entry. Caseworkers will instead have more time to develop specific interventions whilst managers will have more time to spend on coaching their teams and developing external partnership opportunities.

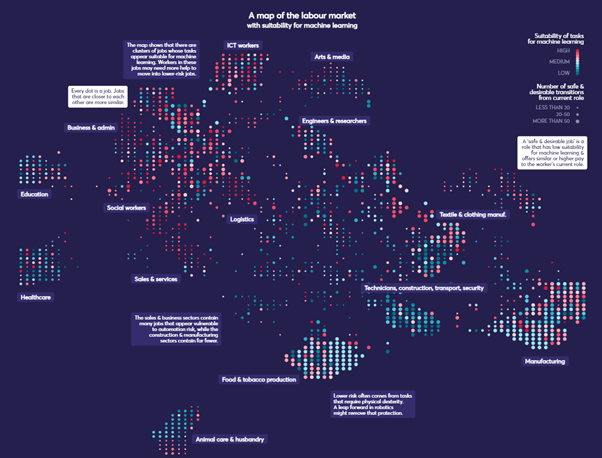

NESTA has used machine learning to produce an interactive map of the labour market with suitability for machine learning (see below) which identifies the similarities between over 1,600 jobs and compares their risk of automation.

Built on an understanding of skills and work activities in each role, it reveals clusters of jobs in which the core tasks appear most suitable for machine learning. Jobs within the sales and business sectors appear to be most vulnerable to automation risk. By contrast, roles in the construction and manufacturing sectors appear to contain fewer jobs which are vulnerable to automation. The map also provides insight into worker resilience by providing guidance on how workers can transition out of ‘at risk’ occupations into lower-risk roles. The research finds that the risk of automation is likely to be hard for employees in certain occupations to escape because occupations that are at high risk of automation tend to require similar skills. It identifies the need to focus reskilling efforts, particularly on at-risk workers in sales, customer service and clerical roles.

There are concerns that these sectoral changes could result in a greater geographical concentration of job growth over the next ten years. Research suggests that unless Covid-19 leads to considerable changes in employer and employee preferences for less dense communities, the same 48 megacities and superstar hubs that contributed 35 per cent of the EU’s job growth in the past decade could capture more than 50 per cent through 2030. For the UK, this trend is likely to mean a continued concentration of high-skilled jobs in London and the South East.

Which trends provide the greatest opportunity for change?

Over recent decades the West Midlands has suffered from low qualifications levels, comparatively high unemployment and low/poor jobs growth, albeit there have been recent improvements in skills levels. Whilst certain of the predicted trends might at first seem alarming, there are opportunities for firms to respond positively.

By investing in training, firms can build on the existing talent within their workforce and prepare themselves for the changing labour market. Deloitte emphasised that the pandemic reinforced the importance of “understanding what workers are capable of doing than understanding what they have done before”. Emerging from the pandemic employers should “double down on commitments to building a resilient workforce that can adapt in the face of constant change”.

One way in which employers can seek to shape the opportunities made available to, and the incentives for, employees to participate in skills development and use their skills in the workplace is through developing the quality of managers and a broader institutional culture which champions training. This can be facilitated through identifying clear training goals, improving skills development and skills utilisation systems within the organisation and establishing of clear internal career progression paths which raise awareness of training benefits. Improving data relating to training outcomes is also important in informing better training decisions. Managers need to develop their own skills in terms of supporting staff. This should not be limited to day-to-day organisational working requirements but extend to supporting staff to participate in skills development. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in accelerating the more widespread adoption of remote and hybrid working requires managers to develop new skills to best manage workers who spend more of their time outside traditional office settings.

The table below illustrates the importance of investment in upskilling and reskilling to wider economic development and progress in addressing social inequalities in the West Midlands in two contrasting scenarios.

| High levels of investment in upskilling and reskilling | Low levels of investment in upskilling and reskilling |

| Clear skills pathways which enable school leavers, graduates and employees to effectively upskill across the life course | Poor relationships with employers and skills providers (schools, Further Education, higher education) |

| The risk of increased youth unemployment is reduced as, thanks to strong strategic partnerships, school leavers and graduates are equipped with the skills required by firms in the region | Increase in youth unemployment as school leavers and graduates lack the skills required by firms within the region |

| The risk of increased unemployment across age groups is reduced thanks to effective and upskilling programmes within firms and partnerships with skills providers. Training opportunities are fostered within firms by organising developing the quality of managers and upskilling initiatives being actives led by senior management | Increase in unemployment across other age groups as roles are replaced by automation and AI and employees lack higher level skills required to move into new roles |

| Firms in the region are highly competitive nationally and internationally. Productivity is driven by high skills levels and cutting edge technology | Decrease in productivity of firms in the region |

| The region is perceived as an attractive place to live, work and invest | Decrease in attractiveness of the region for firms and students |

| Decreasing health inequalities | Widening health inequalities |

| Decreasing economic inequalities with continued progress in increasing skills and employment levels | Widening economic inequalities |

This article is part of a larger project looking at Megatrends in the West Midlands. Megatrends are major movements or patterns or trends that are having a transformative impact on business, economy, society, cultures and personal lives. The project examines some of these megatrends in a series of provocations, podcasts and a report.

This blog was written by Abigail Taylor, Research Fellow, at City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.