Matt Lyons and Raquel Ortega-Argiles provide an analysis of the economic impact of Brexit and Covid-19 on the automotive sector in the Midlands during 2020.

View our Midlands Engine Observatory project page

The automotive industry remains an integral part of the national economy.

The automotive industry is one of the UK’s major employers, supporting over 800,000 jobs throughout the supply chain. The automotive sector is heavily clustered in the Midlands, with the region housing 430 specialist automotive firms including market leaders, Jaguar Land Rover and Aston Martin Lagonda.

The economic benefits to the Midlands are multifaceted. In 2019, 35 per cent of all UK’s automotive employment was in the West Midlands. The automotive sector is export intensive, and the West Midlands is the UK’s leading region making 40 per cent of all cars exported from the UK. The UK automotive sector supply chain is broad with strong linkages to metals, engineering, R&D and other advanced manufacturing sectors.

Covid-19 and Brexit have disrupted industries’ production, demand and trade throughout the automotive supply chain.

The automotive sector saw significant growth from 2008 to 2016. However, the trend has weakened.

Covid-19 has had a dramatic effect on the automotive sector as well. Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) figures show that new car production was down -29.3% in 2020 and 28.7% in 2021 compared to 2019 levels, representing the lowest levels of car production since 1984.

The reasons for this fall in output are found both on the supply-side and demand side. In 2020, multiple automotive firms saw plant closures at large firms. The causes of the plant closures were threefold. Firstly, related to health with employers required to help reduce the spread of infection. Secondly, supply chain interruptions were caused due production closures in China and elsewhere in the world. Thirdly, due to a significant decline in demand.

The significant shock to the automotive sector leads to a series of risks to the Midlands economy. Research by WMREDI revealed that 21 large manufacturing firms in the automotive sector are at high risk due to relatively poor liquidity ratios. The outsized automotive sector in the West Midlands and the sector’s vulnerability has raised concerns that the region may be one of the hardest hit by Covid-19.

Economic Impact Assessment Approach

To provide some analysis of the economic impact the fall in output in the automotive sector has had on the region’s economy, we follow a hypothetical extraction method (HEM) using the Socio-Economic Impact Model for the UK (SEIM-UK).

The SEIM is a multi-regional input-output table built in City-REDI. The SEIM shows a complete picture of the flows of goods and services in the UK economy over one year (base year 2016). HEM involves the extraction of sales and purchases made by a sector from the economic model (SEIM-UK). With the sector extracted, the new smaller hypothetical economy can be compared with the original model to determine the extent of the economic shock.

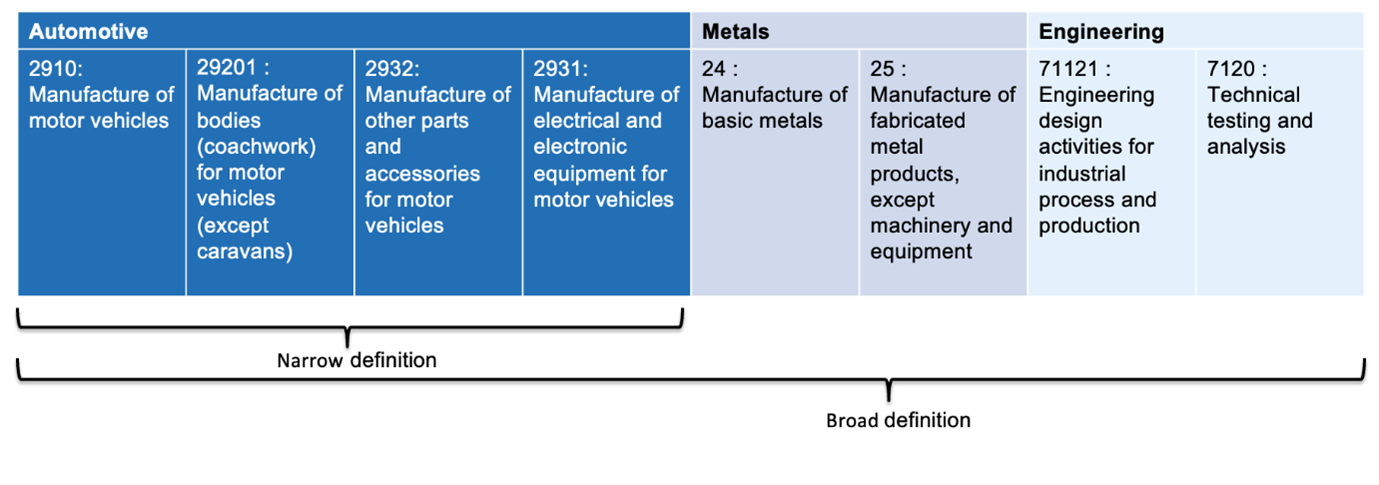

Defining the automotive sector.

The automotive sector is defined in Figure 1. The definition includes activities directly related to automotive manufacturing and the backwards linkages into metals and engineering sectors.

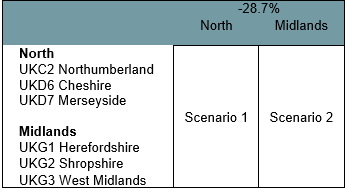

Identifying automotive manufacturing clusters

The automotive sector is distributed across the UK, with one in every fourteen employed in manufacturing being automotive employees nationwide. However, the concentration is as high as one in six in the North East and the West Midlands. This study will focus on the four biggest clusters of automotive employment in the UK (see Table 1). Together, the selected regions accounted for 62 per cent of automotive employment in 2019.

To estimate the size of the shock, we use the latest figures from the SMMT that assumes a drop in output of 28.7 per cent for the automotive sector.

Comparing the shocks

The automotive sector is bigger in the Midlands than in the North, and therefore the negative impacts are more significant. The shock in the North sees some 28,321 jobs lost (FTE) throughout the UK, representing 0.09% of all FTE. The shock sees 61,211 jobs lost in the Midlands, representing 0.20% of all FTE. In output terms, the shock in the North sees output fall -£4.9 billion in the Midlands -£11 billion.

Table 2: UK level impacts comparing shock in the North vs Midlands

| UK impacts | North | Midlands |

| Total gross output UK (£ millions) | -4903.8 | -10976.4 |

| Output change (% of UK total) | -0.14% | -0.31% |

| GVA UK (£ millions) | -1652.2 | -3863.7 |

| GVA change (% of UK total) | -0.09% | -0.22% |

| Jobs UK (FTE) | -28,321 | -61,211 |

| Jobs change (% of UK total FTE) | -0.09% | -0.20% |

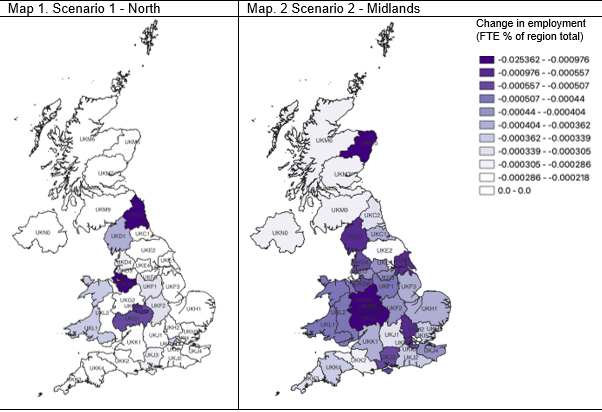

An economic shock to the automotive sector in one region will spillover into other regions due to the interconnectedness of industries across the UK. Figure 2 allows us to understand how a negative shock in the major hubs of automotive sector activity can ripple out across UK regions.

Looking between maps 1 and 2, we can see the most strongly affected geographies where the shock occurred. We can also see that a shock in either the Midlands or the North strongly affects the other. This is to be expected due to the interconnectedness of the automotive supply chain. The shocks also indicate that some regions in the South West, Northern Ireland and Scotland are relatively unaffected.

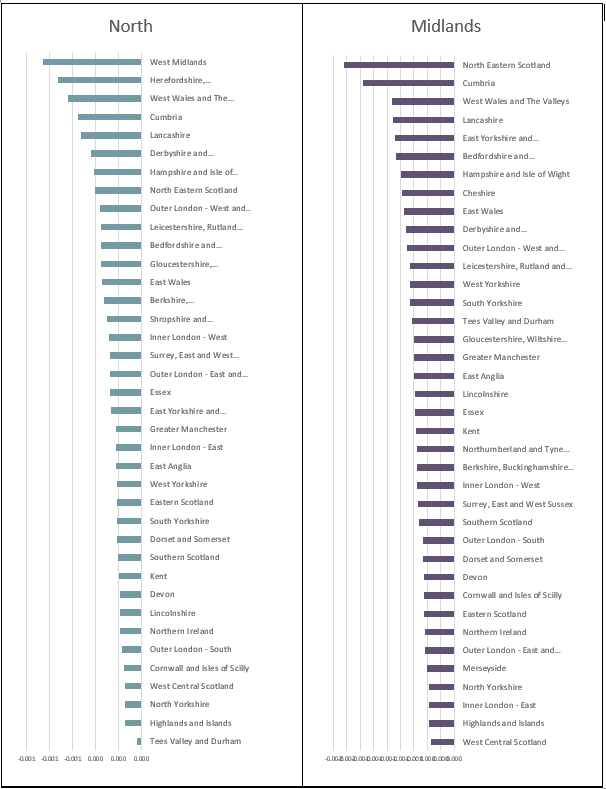

Figure 3 shows the change in output as a percentage of each region’s total output due to each shock. Both graphs exclude the ‘shocked sectors’ under each scenario (see table 1). This allows for the comparison of the most significantly impacted regions outside of the shocked regions under each scenario.

The shock in the North of England most significantly impacts two of the regions in the Midlands – the West Midlands (UKG3) and Herefordshire, Worcestershire (UKG1), followed by West Wales and other regions in the North. This hints strongly that the Midlands is heavily exposed to shocks in the automotive sector.

For the shock in the Midlands, we can see the most significantly impacted regions include North Eastern Scotland, Cumbria, West Wales and Lancashire. These four regions are more rural and less diversified than other regions. They all also share industries with raw inputs to automotive manufacturing such as energy (oil, gas and nuclear), mining and metals. Perhaps surprisingly, areas in the Northern automotive cluster (Northumberland, Cheshire and Merseyside) are not as significantly impacted. From this, we might infer that a large shock in the automotive industry will have outsized impacts in rural regions that provide raw inputs to industry.

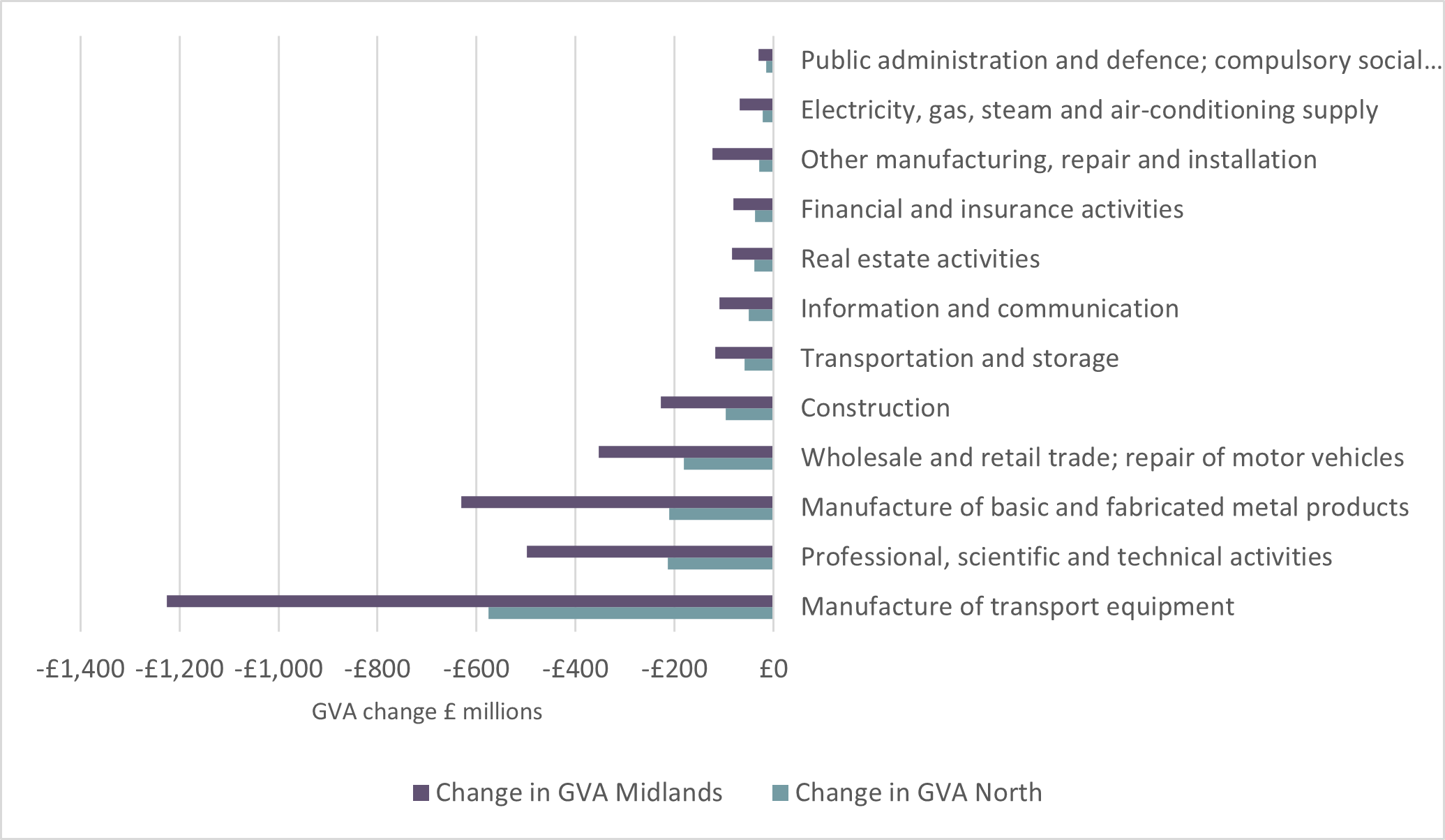

Figure 4 illustrates the changes in GVA of the major affected sectors that are more or less aligned for each scenario, albeit more significantly affected under the Midlands shock scenario. Unsurprisingly the most vulnerable sectors are most closely linked to automotive manufacturing (automotive, engineering and metals). Manufacturing of transport equipment falls by between £575m and £1.2 billion. This is followed by Professional, scientific and technical activities (Engineering) and the manufacture of basic and fabricated metal products (metals).

The next most significantly impacted sector is the sale and repair of vehicles (-£181m to -£353m). This is again to be expected – fewer cars produced, fewer cars passing through car dealerships.

What Does this Analysis Mean for Policy?

This report has provided some estimates of Covid-19 and Brexit’s economic impact on the UK regional economies. The economic picture described suggests the Midlands and particularly the West Midlands, will see a significant economic shock.

Pandemic uncertainty can undermine previous assumptions about regional resilience

The Delta and subsequent Omicron variants have shown that the Covid-19 pandemic is not yet over. The immediate impacts and determinants of Covid-19 for industries and regions are very well understood by the population as well as the analysts (Bailey et al., 2020; McCann and Ortega-Argiles, 2021; McCann et al., 2021). However, the uncertainty of the future of Covid-19 and the knowledge that future pandemics ‘could be worse’ means that evaluating the regional economic and labour impact of such shocks is important for future policy decisions such as implementing further lockdowns. The lockdowns that many countries have instituted mean that the global demand for many final goods and services has collapsed, and many international supply chains (or more precisely, global value-chains) have been stalled. The pandemic has affected places and regions in a very different way. While online services have seen their share prices soar, advanced manufacturing in areas not connected with medical, bioscience or pharmaceutical has seen their productions heavily affected. This evaluation has illustrated regional resilience to the pandemic in regional output (percentage of total regional GVA) in regions with a dominant automotive manufacturing cluster.

The sector is facing multiple crises

Our analysis has shown that the contractions linked with value chain shocks have to be taken seriously and that the degree of severity will differ between places, depending on their economic structures and how governments have responded to it. The briefing has reasserted how important the automotive manufacturing sector remains to the Midlands economy. The sector is facing multiple crises, and the lack of resilience in the Midlands and North of England has been further evidenced. Major UK employers in sectors such as aerospace, automobiles, transportation and retail announced widespread redundancies and a high number of firms dissolving.

Our evidence is part of emerging evidence that points to the economically weaker regions to the UK being the most adversely affected by the coronavirus shock (Innes et al., 2020; Scott, 2020; McCann et al., 2021, among others) and the Brexit shock (Chen et al., 2018; Thyssen et al., 2020, among others). In contrast, the services sectors of London are likely to be the least affected sectors in the medium and long term (Davenport et al., 2020). If the UK government is to achieve levelling up, regions and sectors outside of London and the South-East must be supported proportionately (McCann and Ortega-Argiles, 2021).

The automotive sector is facing significant change over the next decade. Diesel and petrol engines are being phased out with a ban on new combustion engines from 2030 in the UK. The supply chains for alternative propulsion engines may be significantly different to the status quo leading to further uncertainty in the future regional automotive sector. For policy, this means regions like the Midlands will have to recalibrate their labour markets with the help of universities in preparation for demand for new skills and technologies.

Regions have started preparing for these new challenges through large investments such as the construction of a battery electric vehicle (“gigafactory”) plant in Sunderland by Nissan’s battery partner Envision. While this is an important first step the SMMT has stressed that the nine gigawatts hours (GWh) per year of capacity committed by Envision-Nissan represents less than a sixth of the 60GWh per year needed to support the expected mass electric vehicle production in the UK.

The Faraday Institution argued last year that without battery manufacturing in the UK, the automotive industry will slowly decline over time. In the West Midlands, JLR is investing at Hams Hall near Birmingham to assemble battery packs for the new Jaguar XJ EV, but it is again small scale. To ensure industry and regional resilience will be important to have battery cells made in the UK to ensure the auto production remains in the country and to avoid potential currency fluctuations associated with battery cells imports and trade affected by Brexit.

Summary

While there is uncertainty surrounding the economic impact of Covid-19 and Brexit on the automotive sector, the impact in 2020 is likely to have been severe. Concurrent issues of Brexit, microchip shortages, and Covid-19 policy interventions like the furlough scheme complicate impact assessments.

The analysis shows that a sizable chunk of the automotive ecosystem is at risk for the Midlands and the North of England. The supply chain linkages in the automotive sector are broad and have significant regional spillovers. The analysis indicates that these shocks in the automotive sectors will not be contained in their local geographies but have impacts throughout the UK notably in rural areas which house factor inputs.

In terms of the resilience of the sector and the region and given the Net Zero policy agenda, potential solutions should be centred on the provision of battery electric vehicle plants to support the mass electric vehicle production ahead of the 2030 ban on new combustion engine deadline.

View more analysis of the 2020 shock at the NUTS1 level.

This blog was written by Matthew Lyons, Research Fellow, and Professor Raquel Ortega-Argiles, Chair, Regional Economic Development, City-REDI/WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.