This is the second blog in a series on the economic exposure of the West Midlands region [1] to COVID-19. The first article talked about the effect on the main sectors and the employment depending on foreign trade, in an eventual case of international borders closure. You can read the first blog here.

The second economic impact Coronavirus will have on the West Midlands is probably the most important one, the demand for health services. Following the experiences from neighbouring countries, in the coming days, we will see how the NHS will face an incredible increase in the demand for its services. In Spain, the same scene repeats every day at 8pm: everyone is locked down in their homes, they go to their windows and balconies, and pay tribute to the health workers, clapping in gratitude for their wonderful job. Health workers are in the frontline of this crisis, our most vital heroes. However, as it is very well documented by the professors Luis Antonio Lopez and Jorge Zafrilla from The University of Castilla La Mancha in an article for The Conversation (in Spanish), in order to satisfy the health services’ demand, more than just direct workers from the health system are needed, namely additional indirect workers that support them from other sectors. This is what they call Invisible Workers.

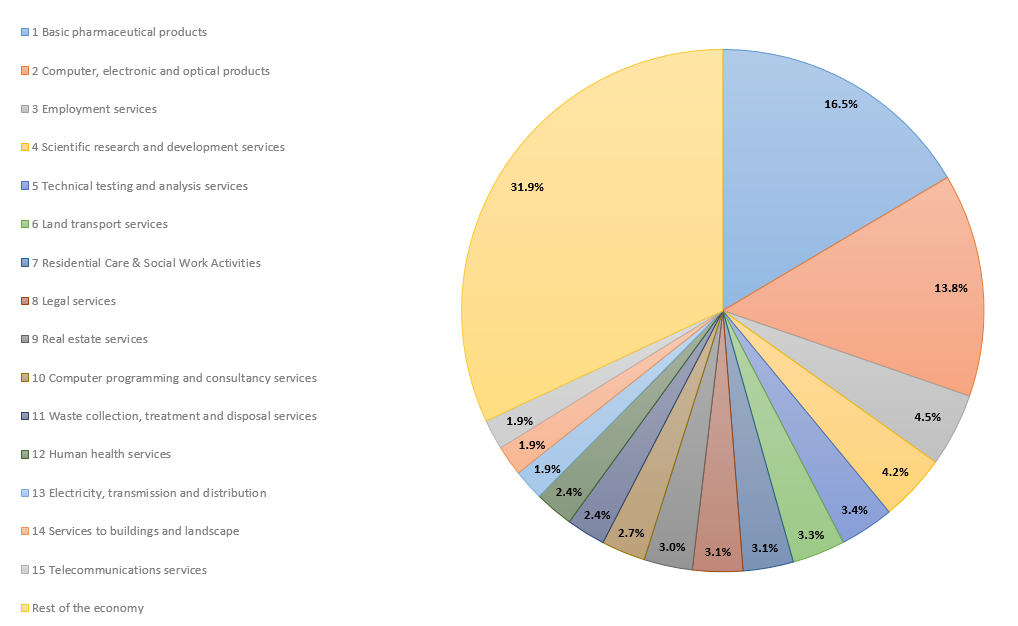

If we take a look at the main direct links that the Human Health Services have in the whole UK (using the ONS Supply and Use tables), we can see that it is mainly connected to sectors like:

- Basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations;

- Computer, electronic and optical products;

- Scientific research and development services;

- Architectural and engineering services; technical testing and analysis services;

- Residential care and social work activities.

These sectors are all part of its supply chain. Figure 1 shows how, nevertheless, human health activities needs from a wide range of sectors in order to produce in normal conditions.

Figure 1. Direct suppliers of the sector Human Health activities in the UK (2016).

Using the SEIM-UK model [2], we can see that the sector human health and social work activities (SIC code Q) are the most important activities for the West Midlands economy. In terms of the number of employees, it is the second only to professional, scientific and technical activities; representing around 14.7% of the total employment (179,500 direct employees). In terms of domestic production, it ranks fourth after the wholesale, retail trade and repair of motor vehicles; manufacture of transport equipment; and real estate activities. Which is 7.6% of the domestic output.

In this second blog, we estimate the employment footprint of human health and social work activities in the West Midlands region. Increasing demand for health services would indirectly mean an increase in the demand for other sectors that supply inputs to them, as we said before, in “normal” conditions [3]. Table 3 shows the contribution of the Health System to the region. As we mentioned previously, the direct number of jobs related to this sector is already large, but if we take into account the “invisible” ones that make possible these activities, the number of jobs related would be close to 216,000. When we see 10 workers providing health care, behind them there are another 2 in the West Midlands region supplying them the inputs they need (in other words, the ratio between indirect workers and direct workers is 0.20) [4].

Table 1. Contribution and employment footprint of Human Health activities.

| Variable | Value | % |

| Output | 10.51% | |

| Gross Value Added | 11.53% | |

| Employment | 17.70% | |

| Number of Jobs | 216,186 | |

| Direct number of jobs | 179,500 | |

| Indirect number of jobs | 36,686 | |

| Ratio (Indirect/Direct) | 0.204 |

Taking into account direct and indirect effects, this sector represents for the regional economy a 10.5% of the total domestic output, 11.5% of the Gross Value Added (GVA) and 17.7% of the employment (in 2016). Note that these large figures are not taking into account the possible induced effects [5].

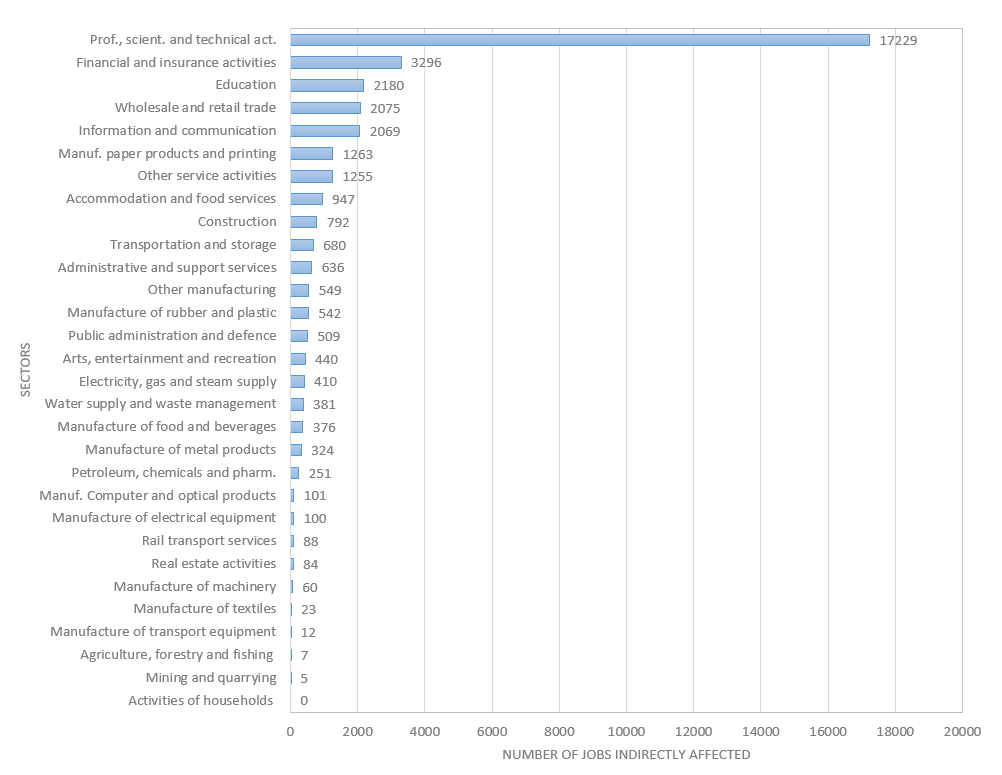

Figure 2 shows the main sectors related indirectly with the health activities and the number of “invisible” workers that are needed for supporting them. The most important one is professional, scientific and technical activities with 17,000 workers, but also financial and insurance activities; education; wholesale and retail trade; and information and communication; appear as very important sectors associated with the Health services within the West Midlands economy.

Figure 2. Indirect employment supporting the Human Health activities in the West Midlands.

The number of jobs from the manufacture of chemicals and pharmaceuticals is not very important in the domestic supply chain of Health activities for the West Midlands because it is quite small in the region (it represents 0,52% of the GVA and 0,22% of the total employment, directly). It means that this sector is importing pharmaceuticals products from other UK regions or from abroad. The same thing happens with optical products. That’s why it is so relevant not to disrupt supply chains [6] (keeping the borders open to allow the movement of, at least, some particular products). It’s also why some local manufactures in most countries are changing their processes to produce ventilators or masks, but even those need specific materials to produce them.

The number of jobs from the manufacture of chemicals and pharmaceuticals is not very important in the domestic supply chain of Health activities for the West Midlands because it is quite small in the region (it represents 0,52% of the GVA and 0,22% of the total employment, directly). It means that this sector is importing pharmaceuticals products from other UK regions or from abroad. The same thing happens with optical products. That’s why it is so relevant not to disrupt supply chains [6] (keeping the borders open to allow the movement of, at least, some particular products). It’s also why some local manufactures in most countries are changing their processes to produce ventilators or masks, but even those need specific materials to produce them.

It is very important to understand the role of the sectors affected indirectly when governments start shutting down all non-essential production. The economy works as an interconnected system that could stop functioning properly if we do not allow for the right minimum flows to keep it working, which requires a good understanding of those flows.

The intention of these blogs is to assess where public financial aid should be potentially directed to mitigate the social negative effects of COVID-19 in the region, and not to centre the debate on whether the lockdown is needed or not due to the negative economic consequences. Life should always come first, and in a crisis like the one we are facing now, resources have to shift to where they are more needed. To health activities. To our visible and invisible heroes.

Read the next page of this blog series:

Footnotes:

[1] In this piece, when we refer to the West Midlands Economy we are considering the NUTS2 classification (UKG3) that includes Birmingham, Solihull, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton regions. An area with a population estimated of 2,916,458 inhabitants (2018) and that corresponds to the West Midlands metropolitan county.

[2] The SEIM-UK model is a Multiregional Input-Output model for the UK with 2016 as the base year developed at City-REDI Institute at the University of Birmingham. Find out more.

[3] Of course, if we reduce health services to the care of those infected by COVID-19 the supply chain would change, however, it is hard to think that the rest of the demand for other health issues would be zero.

[4] In the Spanish case, Lopez and Zafrilla obtain a similar ratio of around 0.25. It is a little bit larger for the case of Spain, as expected, since regions are normally more open and specialized than countries, and due to that their multipliers tend to be smaller.

[5] Induced effects are those ones that appear as a consequence of an increase in the income of the households and the subsequent additional private consumption (and the increase in the aggregate demand). As part of the production process, firms pay wages to the workers (compensation of employees), and that is part of the workers’ household revenues. For this sector, affecting so many employees, the induced effects are presumably very large.

[6] Here we just wanted to show the main implications for the West Midlands region as a closed economy, without considering imports from other regions.

This blog was written by Andre Carrascal Incera, Research Fellow, City-REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.