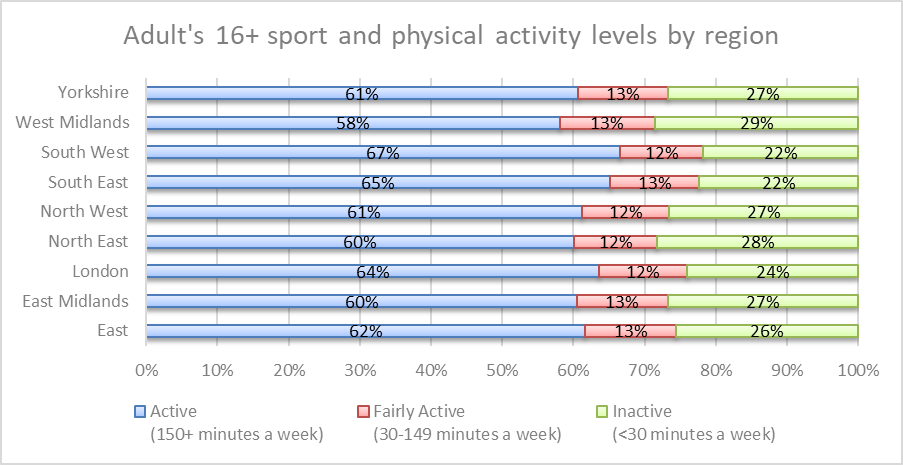

The World Health Organization recommends that all adults aged between 18 and 64 years old should do at least 30 minutes a day of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week to achieve a healthy body mass and weight. Any individual that reaches the level of physical activity recommended according to their age is considered to be physically active (Thivel, et al. 2018). According to Public Health England, a lack of physical activity can lead to obesity and overweight. Obesity and overweight are health issues characterized by increasing the risk of suffering different health conditions including hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes Type 2, respiratory problems, joint and lower back problems, among other problems (Baker, 2018). The statistics in the UK show that by 2015, 25% of adults in England were obese and that a further 36% suffered overweight, summing in total 61% of the adult population suffering overweight or obesity (NHS, 2015). The numbers for West Midlands from the Department of Health show that 22% of women and 23% of men are obese. Moreover, this tendency seems to continue, since according to the latest Active Lives Adult Survey, West Midlands had the most inactive population in comparison with other regions.

The World Health Organization recommends that all adults aged between 18 and 64 years old should do at least 30 minutes a day of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week to achieve a healthy body mass and weight. Any individual that reaches the level of physical activity recommended according to their age is considered to be physically active (Thivel, et al. 2018). According to Public Health England, a lack of physical activity can lead to obesity and overweight. Obesity and overweight are health issues characterized by increasing the risk of suffering different health conditions including hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes Type 2, respiratory problems, joint and lower back problems, among other problems (Baker, 2018). The statistics in the UK show that by 2015, 25% of adults in England were obese and that a further 36% suffered overweight, summing in total 61% of the adult population suffering overweight or obesity (NHS, 2015). The numbers for West Midlands from the Department of Health show that 22% of women and 23% of men are obese. Moreover, this tendency seems to continue, since according to the latest Active Lives Adult Survey, West Midlands had the most inactive population in comparison with other regions.

To date, according to Public Health England, physical inactivity is the cause of one in every six deaths in the UK, which in turn, has an estimated cost of £7.4 billion annually (including £0.9 billion solely for the NHS). This makes clear then that physical inactivity has negative impacts at the individual level but also it carries an economic cost for the society. Therefore, it is important to prevent inactivity and encourage lifestyles that are more active.

One way to achieve this is by encouraging the use of active transport for travelling to work or for recreational trips. Research by Flint and Cummins showed that there is an association between active commuting and healthier body weight and composition. Active transport includes walking, cycling, and other variants such as wheelchair, scooter and handcart use (Litman 2018) for daily commute (or utility) or for leisure (or recreational) trips. In fact, commuting by active transport is considered the easiest way to incorporate physical activity into people’s daily routine (NICE, 2012).

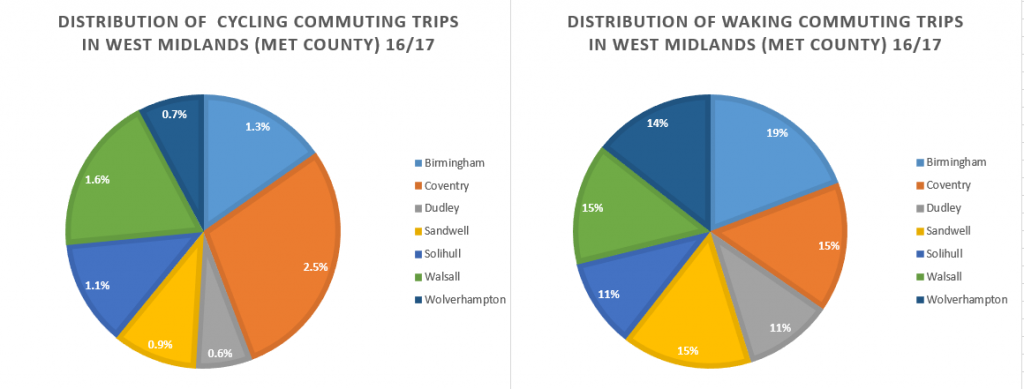

Looking at the current figures of modal share specifically for walking and cycling numbers are not very encouraging. According to the Department for Transport in England, the total commuting trips made by bicycle [1] are 2% and for walking [2] 16.7%. West Midlands shows the smallest proportion of cycling trips together with the North East (1.3% each). For walking, both regions also show the same low tendency (13.7% and 13.8% respectively). The distribution of walking and cycling trips in the West Midlands (Met Country) also show important differences in the travel behaviour across the districts, where Dudley shows the smallest proportion of walking and cycling trips.

The question here is why despite the several benefits from increasing the number of trips by walking and cycling (benefits that go far beyond health such as reducing air pollution and congestion) the statistics remain quite low. Moreover, what are the local authorities doing to reduce these barriers and encourage increase active trips?

To answer the first question, researchers have identified different barriers for walking and cycling which can be divided into personal (perception, attitudes and past behaviour or habits); environmental (weather, topography and distance travelled) and physical (such as lack or inadequate infrastructure as well as lack of facilities such as showers at work) (Bird, et al. 2018, Horton 2016, Pooley et al. 2011).

Authorities in West Midlands recognize the potential of walking and cycling to commute in short distances (up to 1 mile for walking and up to 5 miles for cycling) and authorities state the need to tackle West Midlands’ high obesity levels and diabetes through a transport strategy that encourage more walking and cycling. Therefore, they had set up a series of strategies to encourage walking and cycling.

In the Movement for Growth: the West Midlands Strategic Transport Plan the walking strategy includes “Key Walking Routes” which comprises widened and repaved footway; new and improved pedestrian crossings; improved accessibility through step-free access; removal of hiding spaces and blind corners; street lighting for pedestrians among other measures and “Area wide residential road 20 mph speed limits”.

About cycling, the strategy consists of developing a new “Metropolitan Cycle Network” which will consist of “high-quality core cycle routes […] using a combination of green corridors, well-maintained canal towpaths and low traffic flow and speed streets”. In February this year, the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) supported a regionally co-ordinated cycling strategy with funding targeted at 26 priority routes, the full report details investment for walking and cycling in the region. It is very important to highlight that WMCA and the seven local authorities are working with several partners (such as Cycling UK, Sustrans, Canal and River Trust, Midland Mencap and British Cycling) to achieve the goal of increase in walking and cycling.

It could be noted that there is strong support for improving infrastructure, which is very important since this helps to reduce the perception of risk, however, research has shown that tackling personal barriers aimed to improve attitudes and change other social and psychological barriers is important to promote active travel, but it seems that these measures have not received enough attention. Research has shown that to promote active travel not only new infrastructure needs to be implemented (Bird et al. 2018, Song et al. 2017), it is necessary additional behaviour oriented measures focused on persuading people to voluntarily change their travel behaviour (aka as soft measures) which can help to ensure actual change and its maintenance over time.

Soft transport policy measures combine techniques such as information dissemination and persuasion to influence voluntary behavioural change towards more sustainable travel modes. For instance, through workplace travel plans, school travel plans, personalized travel, marketing of public transport, and travel awareness campaigns (Bamberg et al. 2011). The Local Transport Plan 2011-2026 (West Midlands Local Transport Plan. Making Connections) stressed that “travel demand will be managed through a mix of hard and soft measures to encourage sustainable travel patterns”. But a more detailed strategy on how to implement such measures is needed because this will ensure that the investment in active transport is more efficiently applied.

It is clear that lack of physical activity is leading to suffering different illnesses that negatively affect individuals’ quality of life but also there is a negative impact on society as a whole. Incorporating active transport such as walking and cycling, as part of the daily routine can help improve health and reduce absenteeism from work but more importantly, reduce the cost to the National Health System for treating illnesses that result for physical inactivity. Increasing walking and cycling also can help to tackle other problems such as congestion and poor air quality. The West Midlands Combine Authority has set a series of actions to increase the number of people that walk and cycle with a strong focus on infrastructure improvements, which is important but investigating and tackling barriers of social and psychological dimension play a very important role too.

[1] Adults (18+) that cycle for travel five times per week (2016-2017)

[2] Adults (18+) that walk for travel five times per week (2016-2017)

This blog was written by Dr Magda Cepeda Zorrilla, Research Fellow, City-REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.

A great article that supports the aims of No Limits to Health CIC which I have set up from my passion for cycling from my teenage years living in inner-city Erdington, Birmingham. Cycling kept me healthy, enabled me to explore my local area and beyond, was great fun and still is for me today.