Johannes Read discusses his career so far and how it has changed in ways he didn't think were possible, allowing him to create impact and change to become an Evaluator. This article was originally published in the Evaluator. Find out more about our Evaluation Lab.

I came into this profession two years ago not knowing about the discipline of evaluation. There, I said it.

I work as a Policy and Data Analyst at the City-Region Economic Development Institute at the University of Birmingham. In 2022 I became the UK Evaluation Society and IPSOS UK Early Career Evaluator of the Year. My interests are in evaluating economic development and connecting the links between economy, people, and place. I have evaluated the impacts of several economic development projects. My first project was developing a toolkit to support flexible enterprise learning projects for under-represented students delivered during the pandemic, for which I won the Early Career Evaluator of the Year prize. I am proud of what I achieved and where I started out, in local government in my home city of Lancaster in northwest England. But, until two years ago, I had no idea about the discipline of evaluation. And now I want to share my story of how I became what I would now describe myself as an evaluator.

Towards the end of 2020, I was ready for a change. Personally, and professionally. The pandemic had put on hold my plans to move away from home, something that many people can relate to. Even though I did not know about the discipline of evaluation, one overriding thing was on my mind: impact.

I really enjoyed my role at Lancaster City Council. I had just come fresh from my master’s degree researching local economic development. Economic, social, and health inequalities surround us, particularly in Morecambe, a seaside town neighbouring Lancaster that seemed to be on a perpetual downswing from the decline in UK-based tourism. Specifically, my research focused on the premise that, if economies can change over time, indeed, they can change in an inclusive way. In places like Morecambe, institutions such as Lancaster City Council can make an impact.

That is how my role in evaluation started. I was an officer in the economic development team, and I was working on what difference Lancaster City Council could make to support the local economy.

How could the council work better with local businesses to ensure as much money helped the local economy as possible? Where did we stand, what was the baseline? What was the best approach for support? How can we monitor and evidence the difference we have made? Without realising it, I was thinking, acting, and working, as an evaluator.

Evaluating the Impact of Student Knowledge Exchange

I am in a suit sitting in front of a computer screen in my childhood bedroom. No, I have not just reached a cup final on my Football Manager save. Although I am in the very same room, and at the very same desk, where I drew pictures of my favourite Blackburn Rovers players as a kid, I am now in an actual grown-up job interview. From the Zoom call ether comes the question “Can you explain how you might ….”. Then there’s momentary radio silence. My heart starts to pound, and my head tries to fill in the gaps. What’s going on? It is, of course, a job interview during lockdown.

What the question really was about was how I might evaluate the impacts of student knowledge exchange. My mind was whirring. I was thinking about how to use quantifiable metrics to identify the “soft skills” that students learn from their internships and add to that a qualitative approach to understand the softer elements of learned skills. What I did not know at the time was that this approach would shape my work over the next 18 months. I got the job.

My role was to evidence the impacts of a novel virtual approach to knowledge exchange. In short, knowledge exchange looks at the transfer of ideas between academia, students, and local businesses. My work would form part of the Office for Students’ student engagement in knowledge exchange programme I would work alongside colleagues from the University of Birmingham and Keele University. The programme sought to provide short-term, flexible, online internships and enterprise events would have to support students who are under-represented in higher education to access and benefit from these activities. My colleagues had years of practical experience in providing innovative solutions to under-represented students and knew, anecdotally, of the difference this made for students.

My role was to provide an evaluative toolkit to not only show the impact of our project in Birmingham and Keele but also to share tools to support the evaluation of knowledge exchange across the wider higher education sector.

The first thing I looked for was how the project fits into the big picture. I did this by developing a theory of change and seeing how the project plugs into bigger processes such as the Knowledge Exchange Framework (a first iteration of capturing the impacts of knowledge exchange), the Access and Participation Plans (highlighting the universities’ approaches to tackling the inequalities in access and attainment of students in academia), and the local economic plans (which set out the strategic economic sectors that students will work in and support). The picture started to build up that the impacts spread far and wide; to benefit students, academic research, local opportunity providers, and the local economy.

The multifaceted project required a variety of evaluation methods. This identified the most relevant, practical, and ethical ways of evaluating. A thorough literature review of the novel approaches to evaluation helped identify the most appropriate methods. Building on the Six Steps to Heaven approach by David Storey, it was possible to apply the most relevant methods to the project.

Then I had to make them accessible to busy professional services staff within universities responsible for programmes. This required testing and several iterations of different formats resulting in accessible guidance such as shown in Figure 2.

| Suitable Evaluation Approaches | Top Tips |

| Use pre-event surveys to set a benchmark for student skills, confidence, or knowledge. The evaluation is used for more in-depth comparisons. | Reflect on previous programmes and identify the added value that this programme can bring.

Use unique identifiers such as Project IDs to be able to link data and anonymise student data. Use Likert scale questions to quickly identify trends in the data using Excel or similar. Consult legal teams for advice on GDPR. |

| Consult Access and Participation Plans to ensure the project supports diversity, equality, and inclusion objectives. | Consider ‘How can this project support the Access and Participation Plan?’ and ‘What skills or knowledge do we want to evaluate?’ |

| Host regular Student Shape-It Workshops so students can provide feedback and make improvements to their experience. Evaluates the difference the programme has made for students. | Provide officers with time and resources to host regular workshops and read over logs from students to gather feedback.

Reflective logs should be completed weekly and use the STAR (Situation, Task, Action, Result) format so students can use their experience ready for future interviews, CVs, and cover letters. |

| Submit reflective logs to track the student journey over the course of the programme. Evaluates the difference the programme has made for students. | Students can use their experience ready for future interviews, CVs, and cover letters.

Consider how barriers to accessing knowledge exchange opportunities can be broken down, such as the impact of bursaries, accessible language, altering the format to provide virtual online opportunities, or offering part-time opportunities with roles spread over several weeks. |

| Use post-event surveys to compare with the student position pre-event and identify change. The evaluation is used for more in-depth comparisons, whether with similar students on the same project, students on a different project, or students who have not taken part at all. | Include relevant questions in both pre-and post-event surveys to allow comparisons to be made.

Breakdown analysis by student characteristics to identify impact for different groups of people. Comparing with students from similar ‘career readiness’ stages could be a good option for analysis. Provide space for both qualitative and quantitative responses in surveys. Analyse quantitative responses to give a high-level overview before digging deeper by analysing qualitative responses. Incorporate the same questions in the evaluations of future programmes to compare the impact one programme makes compared to another. |

Figure 2 Methods for evaluating the impact of knowledge exchange for students

Evidencing Impact and Making a Difference

It was only when I was six months in that I realised the importance of working closely with the project teams. I remember visiting Keele for the first time, having worked remotely due to the pandemic and seeing just what a difference the hands-on support that the team provided made to the students they worked with. It was at that moment that I realised I was not just developing a toolkit to evidence impact; I was helping show the real contribution of the staff and their work supporting and maximising the experience of hundreds of students. I still look back in wonder at how my mindset changed that day. At that moment, I realised the need for real-life and real-time evaluation approaches and the need to adopt a developmental approach to evaluation. I adapted my approach to the evaluation by starting with a quantitative overview of the impacts and then digging deeper using qualitative methods.

To evaluate the impact of the internships I started with the perspective of students who completed pre- and post-surveys to rate their changes in confidence and skills on a scale of 1 – 5. The comparisons were made between students who had none, or one or more characteristics associated with being under-represented. These characteristics included: a mature student, from an area of low higher education participation (POLAR4 quintiles 1 or 2), from an ethnic minority, had a disability, were the first in a family to attend university, or were a parent. This analysis of impacts showed that, at the University of Birmingham, the change of skills was greatest for students with multiple under-represented characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1 Changes in skills for students at the University of Birmingham, by under-represented background.

| Average of Change in Skills | Not under-represented | One under-represented flag | More than 1 | Average of all students |

| Average of Presentation skills | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.33 |

| Average of Networking skills | -0.11 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.47 |

| Average of Communication/ interpersonal skills | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.24 |

| Average of Digital skills | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.47 |

| Average of Problem solving | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Average of Leadership | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.20 |

| Average of Teamwork | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.31 |

| Average of Motivation | 0.56 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| Average of Negotiation | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.41 |

| Average of Creativity/ innovation | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

| Average of Planning/ organisation | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.29 |

| Average of Resilience | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.39 |

| Average of Average change in skills | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.34 |

| T Test Not under-represented and one under-represented flag | 0.90 | Not statistically significant |

| T Test Not under-represented and more than one flag | 0.03 | Statistically significant |

| T Test One under-represented flag and more than one flag | 0.00 | Statistically significant |

A similar pattern emerges when analysing impacts by student background in Keele (Table 2). Students from POLAR4 Quintile 1 (geographical areas with the lowest higher education participation rates) had a statistically greater improvement in their skills compared to students from the highest (POLAR4 quintile 5). The most significant improvements came from international students. These groups had a far higher improvement in their skills, far above any other group. This shows that their confidence has significantly improved whilst undertaking online virtual internships. Online internships can significantly support international students with their university experience.

Table 2 Changes in skills for students at Keele University, by POLAR4 geographical background.

| Average Change in Skills | POLAR4 Quintile 1 | POLAR4 Quintile 2 | POLAR4 Quintile 3 | POLAR4 Quintile 4 | POLAR4 Quintile 5 | International Students | Average all students |

| Average of Average of Change in Skills | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.19 |

| Average of Presentation skills | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.16 |

| Average of Networking skills | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.27 | -0.14 | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| Average of Communication/ interpersonal skills | 0.38 | -0.17 | -0.10 | 0.36 | -0.05 | 1.14 | 0.15 |

| Average of Digital skills | -0.38 | -0.17 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.08 |

| Average of Problem solving | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.86 | 0.28 |

| Average of Leadership | 0.31 | 0.17 | -0.15 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.10 |

| Average of Teamwork | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.18 |

| Average of Motivation | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.25 |

| Average of Negotiation | 0.38 | -0.25 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.21 |

| Average of Creativity/Innovation | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.27 | -0.10 | 0.71 | 0.21 |

| Average of Planning/Organisation | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.05 | -0.09 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.17 |

| Average of Resilience | 0.56 | -0.25 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.28 |

| T Test POLAR4 Quintile 1 vs Average | 0.13 | Not statistically significant |

| T Test POLAR4 Quintile 1 vs POLAR4 Quintile 5 | 0.01 | Statistically significant |

| T Test International Students vs Average | 0.00 | Statistically significant |

Further, the impacts of knowledge exchange can also make an economic and place-based impact. For example, the project consciously worked to support small opportunity providers in relatively deprived areas. The aim of the project is to support smaller charities, social enterprises, and micro businesses to take part in a virtual internship to support their work. This was through an online internship for a few hours per week and providing a point of contact at the university for support. This approach was intended to be easier for smaller organisations to handle. My role was to evidence whether this came through in practice. The surveys evidenced the significant success of the approach. As evidenced in Figure 5, feedback from participants showed that the project was highly engaging with smaller community-based organisations:

“as a new start-up business, [the intern] provided a lot of help and support”

“[the intern was] vital to the development of the charity … [to do work that] the organisation does not currently have the resources to pursue”

“I liked the flexibility of hours and that it was part time since I have to take care of my aunt and uncle”.

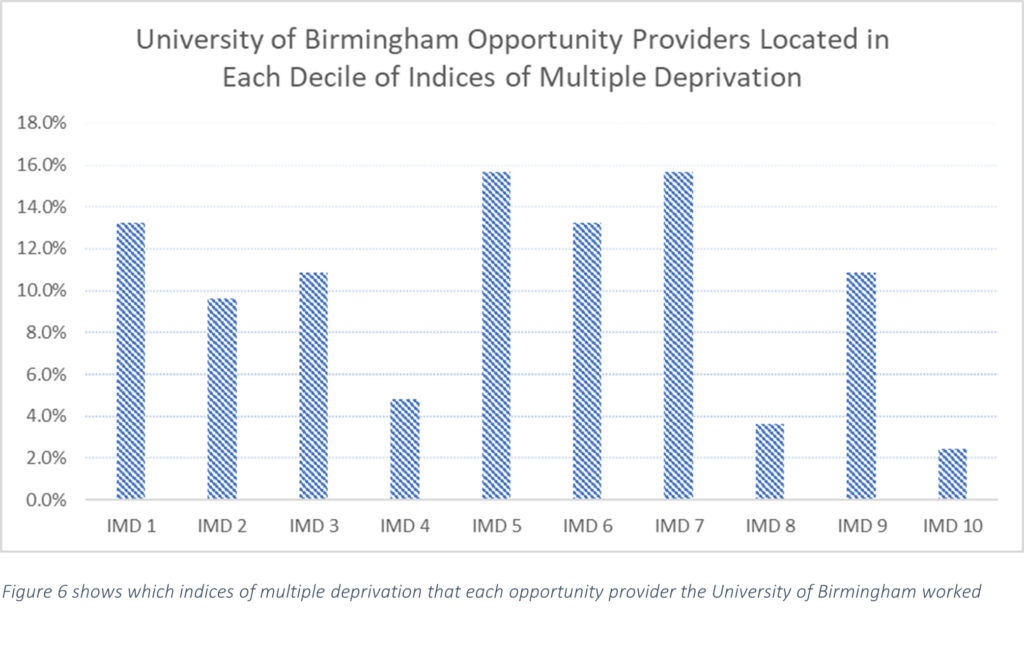

In addition, I evaluated the place-based impacts too. This is to show that the impacts of knowledge exchange are working towards the project’s aims of supporting more deprived areas. The impacts are shown in Figure 6. This shows in which index of multiple deprivations (IMD) decile the opportunity providers were located. With IMD 1 being the most deprived, and IMD 10 being the least deprived decile, there are a significant number of opportunity providers in the more deprived areas. As a result, the impacts of the project are also making a difference for relatively deprived communities, as well as supporting under-represented students and small businesses and organisations too.

The qualitative evaluations evidence the reasons for the effectiveness of the project. The supportive, approachable, and hands-on approach of project staff ensured a greater representation of students, as well as the flexible approach of conducting short-term, flexible, and online internships has supported these students to engage in knowledge exchange activity that would not have otherwise been the case.

The Impact of the Impact Toolkit

Legacy is important for impact toolkits. This is not just another piece of work that sits on the shelf, and that is important to me. As a result of evidencing and evaluating the impact of the internships, the Universities of Birmingham, Keele and Portsmouth have all embedded new practices. At Birmingham and Keele, the evaluations have influenced the provision of ongoing, short-term internships. This is because the evaluations have evidenced the impact on under-represented and international students in gaining confidence and skills. And at Portsmouth, the approach to understanding the interconnected impacts of students, staff, business, economy and place has been embedded in the coursework design of the Business Consultancy Project.

The ongoing cycle of innovation, improvement, and seeing impact is what makes me proud of the student knowledge exchange project. And it is this experience that makes me want to evidence impactful work as I go forward in my career as an evaluator.

This blog was written by Hannes Read, Policy and Data Analyst, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.